Meet Cynthia Sears, Champion of the Arts

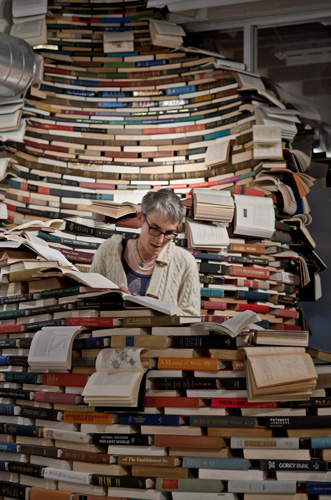

Cynthia Sears is a creativity explorer and the founder of the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art (BIMA) on Bainbridge Island in Washington State. She is known for her extensive support of artists, writers and cultural entities. Her collections include paintings and sculptures; antique and finely bound books; and some 1800 artist’s books, which comprise the Cynthia Sears Artist’s Books Collection at BIMA.

A pioneer in cultural support, Sears has collected and donated numerous works of regional artists to BIMA, creating a rich legacy of Pacific Northwest artistic production. Her wide ranging appreciation of the arts is demonstrated in BIMA’s community-centered mission and diverse programming which includes musical and theatrical performance; hands on educational activities; lectures, tours, and a wide array of community outreach events including an online series Artist’s Books Unshelved. This year BIMA is launching four generous biennial awards to support both regional artists and an artist making books. These BRAVA Awards (BIMA Recognizes Achievement in the Visual Arts) are in celebration of the tenth anniversary of BIMA in 2023, and a further expression of Sears’ belief in the value of the arts to human existence.

We conversed via zoom over a span of four months, discussing a range of subjects which touch on aspects of Cynthia’s life and thinking, including her work in radio and film, social and environmental issues, collecting and philanthropy, education and the arts.

Nanette: What is your background: growing up, education, early careers?

Cynthia: I spent my childhood in Beverly Hills. I went to public school through eighth grade and then to a girls’ boarding school in Virginia, Chatham Hall. I was actually relieved that I wasn’t going to Beverly High because the girls that I knew in 7th and 8th grade who were going there were so much more sophisticated than I was. They were very concerned with boyfriends and convertibles and cashmere sweaters. . . they were already like late teenagers. I wasn’t ready for any of that. The idea of going off to a place where you had lessons in the morning and then rode horses in the afternoon was heaven. My older sister went to Chatham first. I couldn’t wait to go because I met many of her friends, whom she would bring home during vacations. They were great, interesting girls, so I couldn’t wait to go. Going to that boarding school was one of the great experiences of my life.

Then, I went to college at Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania, also a small institution. The entire student body was only 750 girls. It was out in the country and beautiful. I just loved it. It looked like a medieval fortress—towering gray stone buildings which were built out of mica schist which catches the light so that it sparkles in the sun (I learned in my geography class).

I studied English Literature and Latin. I was sure I was going to be a writer. Well, that didn’t happen, but I was convinced of it when I was in college. I had a wonderful experience with terrific people.

Nanette: What happened after college?

Cynthia: After college I got a wonderful job teaching in the Bronx. I was a teacher at the Hoffman School. It was a school for kids who didn’t exactly fit other places, either because the child was super intelligent and could get bored in a regular classroom, or kids who had physical or mental challenges. They were all mixed together in the classes and it really worked. It was extraordinary.

I was hired as a Latin teacher. I taught Latin to second through sixth grades. We made Latin books and grammar books. They would say things like, “If the verb goes at the very end, how do you know who is doing what to whom? Maybe you make sounds so that you know this is the person who is doing the throwing and this is the thing being thrown.” They basically invented the accusative case.