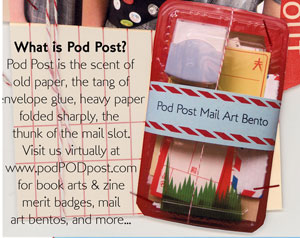

Pod Post, the mail art duo comprised of artists Carolee Gilligan Wheeler and Jennie Hinchcliff, has become an icon at Bay Area print, book, and zine fairs. Their presence is memorable in part due to their complete-with-merit-badge uniforms, their much sought after collectible mail art ephemera, and their passion and advocacy for all things postal.

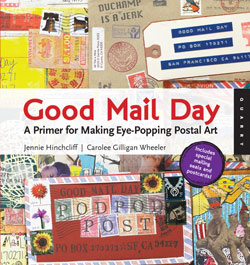

In late 2009 their book, Good Mail Day: A Primer for Making Eye-Popping Postal Art, was published. It quickly sold out and has gone into multiple printings. Good Mail Day—a resource rich in visual, historical, conceptual, practical and hands-on information—was created by two inquisitively whimsical pods who know how to correspond.

Whirligig: What is Pod Post?

Carolee: Pod Post—the name—started out as a brainstorm when Jennie and I were on the airplane to Tokyo in 2005. We like alliteration, and we had been playing around with the concept of a pod as a carrier of potential. After that, we discovered that one of the early national mail delivery services was called Post Office Department.

Pod Post originated as an umbrella for our postal and correspondence obsession, and we started making things under that name, rather than our individual “press” names (Jennie’s was Bubble and Squeek at the time, and mine was superdilettante), to denote that it was a partnership separate from our individual work.

Jennie: Carolee summed up the idea of Pod Post nicely—the entity came about organically, based on our mutual love of all things postal and correspondence related. Once we started appearing together at book fairs and expos as “the Pods,” we quickly realized that there were plenty of other folks out there who were just like us: people who agonized over the perfect fountain pen, searched eBay for exotic airmail envelopes, and knew their postal carrier by first name.

Whirligig: How did you come together to create Pod Post?

Carolee: I had just started to transition from library school into book arts, and Jennie and I ran into each other at the 2004 BABA Book Arts Jam. We liked each others’ style, and she encouraged me to start volunteering at the San Francisco Center for the Book, which I didn’t even know existed! It changed my life. Soon after that, we started conspiring and collaborating.

Jennie: In 2004 we saw each other’s work at BABA. Soon after that, Carolee became a volunteer at the San Francisco Center for the Book (I was working there at the time). It was a sort of “hey, let’s make some cool stuff together!” moment.

Whirligig: Is this how you met, at a Book Arts Jam, or did you know each other previously?

Carolee: We did, in fact, meet at the Book Arts Jam. It’s why it has such a special place in our hearts!

Whirligig: Were you both already independently involved in mail art or ?

Jennie: I have always sent oddball things to friends through the mail; high school and college saw some rather elaborate packages and letters sent to friends and family! When I moved to San Francisco in 1991, there was already a mail art “scene” firmly in place: Picasso Gaglione was running StampFrancisco (sort of a community center for mail artists), John Held Jr. (archivist and mail art networker) would move here from Dallas (1995 or 1996), Networkers such as Harley (faux postage), Patricia Tavenner (long time networker) and Mike Dyer (networker and faux postage) were continuing and encouraging mail art more than ever. I would meet these Bay Area mail artists later in the 90’s. To me, that’s one of the incredible things about networking via mail art: you can correspond with someone, feel as if you know them quite well, but never cross paths in person. Or perhaps your paths cross, but you might not know it. There’s something very synchronistic about the whole experience.

In the introduction of Good Mail Day, Carolee mentions that we really got to know each other well by writing letters back and forth. This is oh-so-true. You can tell a pen-friend all sorts of things in a letter, things that you might not necessarily want to say outloud or mention in the presence of other folks. Mail art is intended for someone specific; as the creator, you tailor the experience to the person receiving the letter (at least I do!)

Carolee: I was a letter-writer from junior high on, and in high school I had a lot of really creative correspondents who pushed the boundaries of “normal” letter-writing and packaging, but I wasn’t really aware of mail art until college when I started getting involved with reading and writing zines. I was making mail art similar to what’s seen in the book—elaborately decorated packages, illustrated letters, using unwanted prints of my photographs or magazine pages as envelopes—but I’d never really explored the whole 3D oddity of mail art until Jennie and I started corresponding. And although I’d studied things like Dada and Fluxus in school and dabbled in that myself, I wasn’t aware of the “famous” mail artists or much of the venerable history until we started writing the book.

Whirligig: As Pod Post , you have in a relatively short time, developed both a considerable following, and have published a beautiful, creative and engaging book Good Mail Day (which must have been a least a two year project). How does your collaboration play out? Have you developed habits or a procedure or is it different every time?

Carolee: We haven’t really developed a procedure, per se, but with each new project we get together and talk about what the needs of the situation are. The way it usually works out is that we divide things in a way that befits our individual strengths. With Good Mail Day, we split most chapters in half, with the exception of one or two that we assigned individually, according to our interests. For example, the mail art history chapter quite rightfully fell to Jennie. But even with that, we still came together to do editing and honing.

With smaller projects, it’s more like one of us floats the idea and then the other one gives suggestions or makes tweaks. We try to make it as balanced as possible as far as the execution is concerned, but again, we lean toward our individual strengths. I like doing letterpress, for example, or writing code for the website, and Jennie is really much better at giving talks and workshops than I am.

Every project is a new experience and even now we’re working it out as we go along.

Whirligig: What parts of your collaboration work smoothly, what parts are challenging and how do these evolve to positive outcomes?

Jennie: I would say that one of the best things about working with Carolee under the Pod Post moniker is the fact that we have shared passions (obsessions?)—correspondence, mail art, all things postal. In many ways, things don’t even have to be planned out between the two of us. Getting excited about a new project often means finishing each other’s sentences. . . there’s no need to explain in detail, since we’re already on the same page.

I would say that one of the hardest parts of working together has more to do with logistics: we’re both incredibly busy all of the time. Between our respective jobs (Carolee works at the conservation lab down at Stanford; I’m an instructor in the fine art department at the Academy of Art) and side projects, finding the time to come together and brainstorm can be a challenge. We spend alot of time these days composing electronic missives to each other, instead of our preferred method of communication (postcards and letters, of course!)

Whirligig: How did you come to create Good Mail Day? Its design, in some regards, embodies a mail art/dada aesthetic, and it is also visually beautifully, more of a “coffee table book” than your standard “how to.” Tell us about the process of conceptualizing and completing this project. How much input or control did you have on the final design?

Jennie: We were very lucky when it came to putting together Good Mail Day. The work of Pod Post had been featured in a book called The Creative Entrepreneur by Lisa Sonora Beam; a couple of months after that, the publisher (Quarry Books) contacted us and said they had been considering putting together a book about mail art; would we like to submit a proposal? Once it was approved, we were on our way! From start to finish, the entire process of submitting/writing/editing took approximately a year and a half.

We couldn’t be more thrilled with the overall design and look of Good Mail Day. Quarry let us hand-pick both our photographer (Von Span) and layout designer (Maureen Forys of Happenstance Type-O-Rama); a major feat for first-timers! Traditionally, authors are assigned an in-house layout person and photographer. However, from the beginning of the project, Carolee and I had a couple of local names that we wanted on board for the project, folks whose work we admired and that we knew would understand our vision for Good Mail Day. It made a huge difference to work locally: meetings and phone calls and photo shoots were incredibly easy, from an organizational standpoint. For example, we could meet up with Maureen and discuss typefaces/layout considerations face-to-face. When it came time to shoot photographs, Carolee and I got to be on set every time, doing the photo styling and choosing props. Those are luxuries that not all first time authors get to have.

We couldn’t be more thrilled with the overall design and look of Good Mail Day. Quarry let us hand-pick both our photographer (Von Span) and layout designer (Maureen Forys of Happenstance Type-O-Rama); a major feat for first-timers! Traditionally, authors are assigned an in-house layout person and photographer. However, from the beginning of the project, Carolee and I had a couple of local names that we wanted on board for the project, folks whose work we admired and that we knew would understand our vision for Good Mail Day. It made a huge difference to work locally: meetings and phone calls and photo shoots were incredibly easy, from an organizational standpoint. For example, we could meet up with Maureen and discuss typefaces/layout considerations face-to-face. When it came time to shoot photographs, Carolee and I got to be on set every time, doing the photo styling and choosing props. Those are luxuries that not all first time authors get to have.

As for the dada/mail art aesthetic throughout the book. . . well, it was important to us from the very beginning that Good Mail Day be more than just a “how-to” book. There are so few books out there which discuss mail art in general, let alone the history or motivation behind the movement. We wanted to show folks that mail art didn’t just spring up overnight, and it isn’t a passing fad or trend. There is a worldwide community (known as “the Eternal Network”) of individuals who have been working in this genre for years—Good Mail Day is a tribute to them, as well as all of the newcomers who have never heard of mail art before. I think the book really captures some of the core beliefs of mail art: anyone can be a mail artist and there are no artistic requirements or boundaries. It is an accessible way of artmaking, and all are welcome.

Whirligig: The term “networker” then comes from “the Eternal Network” of mail art? (I was curious about this when reading your book.) Do you know the origins of this usage?

Jennie: On page 15 of Good Mail Day, there is a quote from the French Fluxus artist Robert Filliou which references an “eternal network” of all artists, a network constantly evolving and changing. The mail art community has always been closely allied with the concepts of both dada and fluxus; at the time (1963) it seemed a natural fit to adapt the idea of Filliou’s Eternal Network to mail art ideals. When you think about about it, mail art is all about creating a personal network for one’s self: a group of folks that you correspond with. These people, in turn, pass your name on to others, who write back and continue the chain. . . the effect is like a stone being dropped into a pond, and the water ripples out exponentially, to reach others.

Whirligig: What is the social significance of mail art?

Jennie: Because mail art is such a young, 20th century “happening,” I think it’s too early to tell, in a large “art movement” kind of way. But on individual and personal levels, correspondents and artists have used mail art to draw attention to all sorts of causes or global situations: politics, oppression of/by governments, social ills, or economic concerns are all topics explored by mail artists internationally.

Whirligig: Share with us an example of how you may have changed someone’s life based on a creative project of yours that they have experienced.

Jennie: Â Hmm. . . that’s a big question. I don’t know if we’ve changed anyone’s life, per se. Time and time again, people tell us how important they feel handwritten letters are (especially those received from relatives or long-time friends), how they become cherished objects to the person who receives them. I think this is such an important thing to remember. It’s such a simple thing, to write a friendly note or postcard to someone, and it can mean so much to the recipient. Such a small amount of time, to make someone happy.

Carolee: I know I’m going to be in danger of rolling out the nepotism on this one, but writing Good Mail Day with Jennie had a really unexpected benefit for me. I’ve lived very far away from my family for fifteen years now, and as a result they’ve always been kind of out-of-the-loop about my day-to-day diversions, or the way I spend my time. I never really thought that my dad had any interest, really, in what I was up to, but when the book came out, he bought three copies. That was nice, although it was kind of par for the course, he being a very supportive parent. “Make sure you read all the way to the end, Dad,” I told him, because I’d given him a shout-out on the acknowledgments page (as a postal worker and supportive dad, he got me started with pen pals and always indulged my lust for stamps). What I was not expecting at all was what came next: he started sending me a hand-written letter every other week, with really crazy marker drawings on the outside of the envelopes. I hadn’t seen my dad draw a picture since he’d drawn with me as a little girl. That was cool enough. But then he told me that he had started sending decorated letters to lots of other people—long-lost relatives, or the little children of his neighbors, and he told me that everyone he sent mail to was tickled pink and intrigued, wanting to do more of that themselves. Now, if THAT’S not great enough, he made a different drawing on all the Christmas cards he sent out this year. Imagine how that stood out in the sea of plain, unaugmented greetings! My dad is kind of a solitary guy, and doesn’t really socialize much, and most of his lifelong friends and immediate relations (including my mother) have passed on. But sending out these special Christmas cards got him dinner invitations (which, surprisingly, he accepted) and tons of personal replies in response.

Carolee: I know I’m going to be in danger of rolling out the nepotism on this one, but writing Good Mail Day with Jennie had a really unexpected benefit for me. I’ve lived very far away from my family for fifteen years now, and as a result they’ve always been kind of out-of-the-loop about my day-to-day diversions, or the way I spend my time. I never really thought that my dad had any interest, really, in what I was up to, but when the book came out, he bought three copies. That was nice, although it was kind of par for the course, he being a very supportive parent. “Make sure you read all the way to the end, Dad,” I told him, because I’d given him a shout-out on the acknowledgments page (as a postal worker and supportive dad, he got me started with pen pals and always indulged my lust for stamps). What I was not expecting at all was what came next: he started sending me a hand-written letter every other week, with really crazy marker drawings on the outside of the envelopes. I hadn’t seen my dad draw a picture since he’d drawn with me as a little girl. That was cool enough. But then he told me that he had started sending decorated letters to lots of other people—long-lost relatives, or the little children of his neighbors, and he told me that everyone he sent mail to was tickled pink and intrigued, wanting to do more of that themselves. Now, if THAT’S not great enough, he made a different drawing on all the Christmas cards he sent out this year. Imagine how that stood out in the sea of plain, unaugmented greetings! My dad is kind of a solitary guy, and doesn’t really socialize much, and most of his lifelong friends and immediate relations (including my mother) have passed on. But sending out these special Christmas cards got him dinner invitations (which, surprisingly, he accepted) and tons of personal replies in response.

I like to think that Good Mail Day changed my dad’s life. He’s now more connected to the people in his life, and has suddenly gotten obsessed with drawing and playing with art supplies. From a lonely 80-year old man who was mainly concerned with mowing the lawn and watching TV to a Grandma Moses-type figure who is blowing everyone’s mind with his crazy art. It makes me so incredibly happy.

Whirligig: What are the most interesting or unusual things you have sent and received through the mail?

Jennie: A cardboard pizza box (empty); when opened, the box contained a painting of a pizza (Von Span, USA); a block of styrofoam which got lost in the back room of the PO and reached me three months after the fact (James Cline, USA); a stuffed crochet bird, hanging inside a plastic Starbucks-type coffee cup (Connie Vlaicu, USA).

Carolee: I mailed two handmade sock monkeys, as-is, to two of my friends last year. I wrapped them in that industrial plastic-wrap you can buy to wrap furniture for moving, stuck on a mailing label, and mailed them from the robot mailing machine at my local post office. They both arrived in fantastic condition.

The most interesting thing I have received is a clear plastic Starbucks cup filled with cancelled stamps (which can be seen in Good Mail Day) from Jennie. I was out of town at the time, and the person who was housesitting for me said, “I showed up and I thought that someone had just thrown their stupid garbage in your mail chute. Then I realized the trash was actually FOR Â YOU. What’s up with that?”

Whirligig: Tell us about your collections.

Jennie: I always joke with people that my apartment is like one big archaeological dig or apothecary shop: there’s stuff absolutely everywhere! Some people are really good at curating creme-de-la-creme objects in a sleek modern setting; that’s never really been my style. I love living surrounded by objects. As far as my collections go, I love all things USPS related: airmail envelopes, stamp collector’s albums, little tin mailboxes, and my “boyfriend,” Mr. Zip. I also collect old keys, secret society medals, Japanese shuin-choï books used for collecting calligraphy and stamps at shrines in Japan). Anything odd and old—that’s what I collect!

Carolee: Oh man, I’m trying to collect LESS stuff. Like Jennie, I have a (modest) collection of airmail envelopes and beautiful old postage stamps. I have a lot of office stamps, mainly because people give them to me. People send me mailbox trinkets and stationery, of course. But the thing I seem to amass out of sheer obsession is fountain pens. I love fountain pens and am always buying them when I go on trips. Most of them are under $35, so I don’t feel too bad, but there’s no way I could possibly use them all. To go along with that, I also buy a lot of ink. Â I think I have four shades of grey ink. And in the weirdest collection category, I can’t seem to take a run or a walk without coming upon those valet tickets you see on people’s windshields. Some of them are really beautiful, still letterpress-printed, usually in red ink on salmon or white or mint green card. Whenever I see one of those, I can’t stop myself and I pocket it. I have a huge envelope full of them and I have NO idea what I’m going to do with them.

Whirligig: Does that mean the cars will go missing?

Carolee: Ha! No, people are usually too preoccupied to take the tickets from under their windshield wipers (in the non-rainy season, that is). These are just cars parked on the street, not in a valet lot. Most of the tickets I find are on the ground, anyway.

Whirligig: How did you come to be artists?

Carolee: I resisted art for a long time, after art school (I studied photography and did a lot of drawing). I came to dislike the way so many artists seemed to want to be distanced from their audience, elevating themselves by making things that were difficult to understand. After art school, I got your typical art-major jobs; photo developing and picture framing. I made some zines during that time, but ultimately I didn’t make anything for about six years. When I was in library school, I started to realize that what was missing from my life was the physical act of using my hands to create something, as well as the enjoyment of creative problem-solving. That was when I started learning bookbinding, and shortly after that I met Jennie. Things seemed to fall into place, then.

Jennie: Making art is something that I’ve always done, I suppose. I never really thought about it, or set out one day to “be an artist.” I’m a constant maker-of-things; a good friend of mine teases me, saying that my hands are never still, they’re always “curious.” I’ve always been a curious person—I think most artists are, by nature. My restless “doing” ensures that there’s always another question to be asked, another answer to be found.

Whirligig: You produce a substantial amount of product, I am sure at great expense. Is this just a natural part of your business plan or just what it takes to be who you are and do what you do?

Carolee: Actually, we’ve slowed down a lot recently, with the mental and physical energy that was necessary to create Good Mail Day. Initially, though, the decision to produce the merit badges, or bring back a suitcase of bento stuff from Tokyo, required us to make a financial leap of faith. We thought our ideas were good enough that we were willing to spend some cash up front. That paid off.

Now, we’re deciding what direction to go in next. With outlets like Etsy, being craft-based artists has become a lot easier for people, and I feel like that ease and ubiquity has cheapened the process a little bit. We’re considering doing less product-based work in the future.

Jennie: I feel that the product stemmed from a desire to share with other folks in a “hey! look at this cool pencil case. . .” or “check out this groovy stationery!” kind of way. Carolee and I are both seduced by all sorts of graphic design, so it’s been great fun to create product that emphasizes many of the different things that inspire us, on an ephemera level. Ultimately, when coming up with new product ideas, we ask ourselves a couple of questions: “is there anything else like it?” and “would we buy it?” being the two biggies. As for the “at great expense” part, we’ve always felt that if it pays for itself and we’re having fun doing it, then that’s a win/win situation.

Whirligig: What part of your mission provides the least satisfaction in regards to its work load?

Carolee: An essential part of Pod Post has been the way we pose and interact with the public, through elements such as our costumes and our outgoing behavior. I’m naturally more introverted and subdued, so some of that was difficult for me. I can sit around in my studio or in my house and make things all day long (I’m really good at the assembly-line aspect of production), but give me a few hours being “on,” in the public eye, and I’m exhausted. I think Jennie is much more comfortable with the public-persona aspect than I am.

Whirligig: What gives you the most satisfaction?

Carolee: Conversely, spending hours in my house making things doesn’t mean very much if I don’t get out there and meet the people who appreciate the effort I’ve made. So doing events and interacting with people can provide some of the most rewarding moments. It’s all too easy to feel like you’re creating in a vacuum. Shows like the BABA Jam and the Printer’s Fair allow us to meet all kinds of like-minded people.

Jennie: Well, Carolee’s right: I love the showmanship of getting out there and interacting with other letter writers, mail artists, Pod Post fans. We couldn’t do it without them, so it’s great to meet the folks “on the other side of the PO box,” so to speak. So many people have shared so many different and unique stories with us over the course of the last three years—it has given me a whole new appreciation for correspondence in general. I think it’s incredible how people reach out and connect with each other on paper, when nine times out of ten they would feel too shy or awkward or mawkish to say those very same things to someone in person.

Whirligig: Pod Post is on an edge that is clever, intelligent, funny and a healthy critique of society. Yet, it is all very nice. Do you tame ideas that might be more obviously judgmental, interrogating or potentially misunderstood?

Carolee: No. We don’t seem to come up with confrontational ideas within this framework. I know that one of our zines, I Remember These Places When They Used to Exist, was criticized by a couple of people as being too solipsistic and dramatic, but most of our Pod Post projects are friendly. We want people to feel accepted, motivated, and connected.

Jennie: We never set out to do a project that would put people on edge or “rock the boat” in an aggressive way; it’s not what Pod Post is about. We’re just two nice girls from San Francisco who want people to send more mail to each other!

Whirligig: What adjectives would you apply to your work? For example, I have heard Pod Post described as both cute and really smart.

Carolee: Open, inquisitive, aesthetic, and hopefully clever. Cute is okay too. :)

Jennie: I’d vote for whimsical and approachable, with a dash of panache.

Whirligig: You withhold your personal identities for the collective entity of Pod Post. Reflect on this.

Carolee: Whenever you’re talking about a collaborative or group project, you’re absolutely talking about a shared vision, rather than the individuals involved. With Pod Post, we took just one aspect of our personalities—that obsession with mail and book arts—and emphasized it for the sake of the project. Raising that aspect into relief makes the project simpler, in a way, both for us and for outside observers. I think that art quite naturally lends itself to obsession, or I suppose it’s possible that having a singular focus just makes it easier to tune out all the background noise. Now, if you’re talking about my admission that I’m more of an introvert and that I have to suppress that to make Pod Post work, that’s totally true—but I would wager that you’ll find (or have found) more inwardly-focused people in the arts than in other disciplines. The great thing about all of the different aspects of Pod Post is that they exercise many different muscles. The urge to create, the desire to interact with other people, and the challenge of working somewhat outside my comfort zone. I think all of those things stretch me, creatively.

Jennie: Pod Post is a pretty specific idea-based project (mail and book arts), so it makes sense to turn the volume down on other aspects of our artistic and personal lives—that way Pod Post can take center stage, and the two of us present a consistent “Pod Post” image. That being said, when we do vendor fairs and shows, we’ve always had aspects of our “other” lives on the table: Carolee’s superdilettante journals and stationery sets, my Red Letter Day mail art supplies and zine. But it all relates to correspondence in some way, so it’s in keeping with the overall feeling of the things we sell. I think there are hints of our “other” selves that peek through; you just have to know where to look.

Jennie: Pod Post is a pretty specific idea-based project (mail and book arts), so it makes sense to turn the volume down on other aspects of our artistic and personal lives—that way Pod Post can take center stage, and the two of us present a consistent “Pod Post” image. That being said, when we do vendor fairs and shows, we’ve always had aspects of our “other” lives on the table: Carolee’s superdilettante journals and stationery sets, my Red Letter Day mail art supplies and zine. But it all relates to correspondence in some way, so it’s in keeping with the overall feeling of the things we sell. I think there are hints of our “other” selves that peek through; you just have to know where to look.

Whirligig: The museum and the gallery do not seem to be the focus for the distribution of your work. What factors does this have to do with?

Carolee: Long, long ago, when I was in art school, I witnessed, on a small scale, how wanting to work with galleries changed people’s vision and output. In my opinion, showing in galleries has more to do with how much you pound the pavement and who your friends (and enemies) are than it does with the quality of your work. That might sound like a total insult to represented artists, but I don’t mean it that way—I’ve just noticed that there are so many interesting things going on that never get picked up by galleries. Further, I think that art galleries are by their nature exclusive, meaning that they exclude a large part of the population. I got fed up with that back in art school and started focusing on channeling my creative energies into making affordable, mass-produced stuff like tongue-in-cheek t-shirts, creating public installations, and by dabbling in performance art. I believe that art is supposed to be about communicating with other people. That’s why something like mail art is so wonderful. It’s affordable, and it’s a direct communication from person to person.

Jennie: It was never something we aspired to, Pod Post-wise. Ultimately, it was more important to encourage people, foster their creativity, get them involved. Our “Pod goals” kind of embody the exact opposite of that museum based “do not touch” standard.

Whirligig: Where do your interests lie in regards to the high art world and what its critics regard as important work?

Carolee: I like art. Going to museums makes me happy (except when it makes me sad, or frustrated). But I think I would be hurting myself if I thought too much about high art and art critics. When I make something, I want to satisfy myself and communicate with another person. I would love it if at some point in my life, someone important said something nice about me. But thinking about that kind of attention is counter-productive if you’re going to be making things and trying to stay true to your own ideas and impulses.

Whirligig: How do you want the work you are doing now to be considered and recorded?

Carolee: Woof, that’s a tough question. I’m going to defer to the Pod Post project here and say that I hope people will look at Good Mail Day, and our other endeavors, and see them as an attempt to keep alive something that is very basic and necessary to our humanity. That this kind of epistolary communication and personal art-making doesn’t need to be left to the people we consider “professionals”; that we are all artists with our own ideas to share; and that making things with our hands makes us better, more present, people.

Jennie: I think that Good Mail Day has really inspired something in people, something fundamental and essential. I know that Good Mail Day has been set adrift in an ocean of craft and how-to books; I’d like for it to stand on its own as a book filled with inspiration and encouragement, something that readers go back to, keep in their bookcases. We’ve received letters and heard stories time and time again from folks who tell us “I thought that I was the only one doing this” or “everyone in my family thinks I’m a weirdo because I decorate envelopes.” Good Mail Day shows them that they aren’t the only ones, that there’s actually an entire network of people around the globe who make art and send it through the mail and actually enjoy opening up their mailbox. That feeling of “you’re not the only one” is incredibly powerful, and it can change a person’s life. I guess that’s the takeaway I would want people to include in the footnotes.

Whirligig: Is there one individual or institution that you would like to acknowledge your work? Who is that and why?

Carolee: I’m going to be a complete dork here, and tell you my deepest desire: I want Lynda Barry to be my pen-pal. Although there are probably a lot of people out there who don’t know who she is, or think she’s just a cartoonist or something, she has had a profound effect on the way I think about being creative and making things. Reading about her views and struggles has really helped me solidify my reasons for doing the things that I do. She is someone who has followed her own artistic path throughout her life, regardless of whether it brought in the paychecks or brought accolades, and that’s always something I respect in an artist. I think her work goes way beyond drawing, or comics, into tapping into all of the ways we can STOP being half-dead zombies who barely participate in our own lives. Becoming Lynda Barry’s pen-pal, somehow because of my little efforts in thing-making, would be psychological. HA!

Jennie: Hmmm. . . that’s a tough question. I often wonder what it would be like to have received mail from Ray Johnson, or to have gone to one of his NYCS meetings. In the here-and-now, I’d love to meet mail artist Ryosuke Cohen (Osaka) in person. Institution-wise, it would be a dream-come-true to work with the National Postal Museum.

Whirligig: You both produce zines. Can you talk about your interests and involvement with zines? What is the draw and effect of these; and how did you come up with your zine concepts.

Carolee: I started reading zines in college, while I was studying art. I think my disillusionment with the whole elitist art world really drove me towards more populist and accessible expressions of creativity. So when I moved to Columbus, Ohio after graduation and got a job as a photo processor (and had long hours with not very much to do), I started writing and drawing a zine called Bottom Feeder (so-called because my job paid me $5 an hour and I could barely afford a 75c carton of fried rice for lunch, so I did a lot of scrounging around in those days). It started as an illustrated letter (!) to my friend TC—I would draw the weirdest or worst photos I’d processed that day and then write in stories about my strangest customers. Â It then occurred to me that I had access to a copier at work, too, and I decided to send a copy in to Factsheet 5. I did six issues, one (two? I can’t remember anymore) under the moniker Palimpsest (because I’d gotten a better job and agonized over whether I was really a Bottom Feeder anymore).

Carolee: I started reading zines in college, while I was studying art. I think my disillusionment with the whole elitist art world really drove me towards more populist and accessible expressions of creativity. So when I moved to Columbus, Ohio after graduation and got a job as a photo processor (and had long hours with not very much to do), I started writing and drawing a zine called Bottom Feeder (so-called because my job paid me $5 an hour and I could barely afford a 75c carton of fried rice for lunch, so I did a lot of scrounging around in those days). It started as an illustrated letter (!) to my friend TC—I would draw the weirdest or worst photos I’d processed that day and then write in stories about my strangest customers. Â It then occurred to me that I had access to a copier at work, too, and I decided to send a copy in to Factsheet 5. I did six issues, one (two? I can’t remember anymore) under the moniker Palimpsest (because I’d gotten a better job and agonized over whether I was really a Bottom Feeder anymore).

Zines were a really wonderful way for me to connect with people all over the world, through the mail, for a couple of bucks, when I was kind of poor and kind of isolated. I still love, very much, zines that are individual responses to people’s life circumstances and personal growth. I was and am incredibly attracted to the idea that you can really express yourself to a bunch of people who don’t know you, to talk about difficult concepts or personal convictions in this space that is designed, edited, and presided over by you. Nobody else gets to decide what makes the cut. I’m always surprised that more people don’t experiment with zines. It’s such a great way to explore ideas and not have to subject yourself to the arbitrary litmus of edited journals or the gallery community.

I still don’t really see any point in making overly abstruse art. For me, the whole point is to communicate with people. I like it when I feel like someone is taking me into confidence, so I try to make my zines as open as I can without making myself uncomfortable. It doesn’t always work: I sent my early zines to some people who knew me personally and a couple were put off by how forthcoming I was. “You mean you send these to strangers?” one person said. “How can you do that?”

Zines don’t cost a lot to make or buy. You can leave them on the bus for people to find. They’re not as popular as books or music or even comic books, and they’ve never been the same since the Internet exploded and blogging crawled out of the muck. But a well-written, attractive, honest zine still stops my heart, and that’s why I continue. Zines are for everybody.

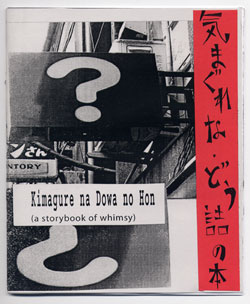

Our zine ideas came pretty naturally, I think, out of our personal interests, obsessions, and brainstorming conversations. For Kimagure na Dowa no Hon, we just wanted to document our trip to Tokyo by reproducing parts of our travel journals. For I Remember These Places When They Used to Exist, it all started with the book of maps Jennie bought at the Tokyo flea market and the idea of physical places being the keepers of certain kinds of memories. And 3-2-2-1 started from an idea my college photography teacher used to help us jump-start our imaginations—the act of choosing library books at random. We just decided to take it further by infusing it with the library-geek concept of MARC record-searching I’d learned about in library school.

While the merit badges and stationery product are more of a “gimme” in terms of popularity, I’m really proud of the zines, because to me they are the more artistic fruits of our collaboration. I like the other things very much, but the zines are more satisfying to me on an artistic level.

Jennie: I have to say, Carolee was the one who inducted me into the world of zines. Growing up in Oregon, I had seen zines at underground record stores and such, but had never realized that there was a whole community of people who called themselves zinesters. My interaction with zines in San Francisco had been pretty limited (I was on the installation crew for SFCB’s “Zines!” in 2002 and had visited the SFPL’s “Little MagaZine collection”). Once I returned to the mail art fold in the ’90s, it seemed like a natural progression to put together a zine for the mail art community, something that would be informative and inspiring. That’s how Red Letter Day came into existence. When Carolee and I began working together, her enthusiasm and knowledge of the genre was infectious—we started creating zines together as part of the Pod Post product line.

The beauty of putting together a zine (for me) has to do with the fact that each zine is a direct reflection of the person who made it; no two zines are alike. All you really need is a photocopier and initiative, in order to make a zine happen. Recently, zines have “grown up” a bit: people are incorporating letterpress and bookbinding skills, bringing them together within the zine format. It’s a pretty exciting time to be making them! When deciding on a concept, we usually tackle subject matter that we’re inspired by or passionate about: travel, journals, memory, the intersection of art and narrative.

The beauty of putting together a zine (for me) has to do with the fact that each zine is a direct reflection of the person who made it; no two zines are alike. All you really need is a photocopier and initiative, in order to make a zine happen. Recently, zines have “grown up” a bit: people are incorporating letterpress and bookbinding skills, bringing them together within the zine format. It’s a pretty exciting time to be making them! When deciding on a concept, we usually tackle subject matter that we’re inspired by or passionate about: travel, journals, memory, the intersection of art and narrative.

Whirligig: You have a reputation as delightful, friendly and giving individuals. What models in your lives have shaped these characteristics in you?

Jennie: I would say that my parents and grandparents were astounding role models. From my parents, I learned about the virtues of hard work and believing in yourself; my grandparents taught me about making books, working with paper, and having the patience it takes to do something really well.

Once I arrived in San Francisco to attend college, I was lucky to have some wonderful role models and friends. Howard Munson was an incredible mentor to have (my first “official” bookbinding teacher!), as well as more recent influences—most notably, mail art friends James Cline and John Held Jr.

Carolee: Why, what a nice reputation to have! Can you tell me who said those things, so that I can bake some cookies for them? To name all of the kind and accepting people who’ve influenced me would make for an awfully long (and rather boring) answer, so I’ll just say that when I was a little child, my mother in particular made a point of telling me that I should be myself, that I should be true to my own best instincts, and that I should never be “a follower.” This was often a response to the teasing I got at school for having an unusual family, or for having interests that were not quite the small-town, Midwestern norm. Being told “what you are is OK” is a pretty powerful thing for a child who’s being ridiculed, and it’s especially meaningful in light of my mother’s very conservative, Catholic, rules-oriented, status-quo upbringing, so that had a powerful effect on me.

It seems that people who are teased either turn into bullies themselves, or they develop a very compassionate attitude toward the people around them. I think I had the latter reaction. I also believe that it’s always more helpful if we can strive for a friendly, kind outlook and to try to have fun if we can, because this is kind of a cramped planet and we’re all in it together.

And, if I can be a little silly for a moment, it seems obvious to me that the whole idea of mail art is about giving of yourself. The ideal, of course, is to get as good as you give, but because there’s no guarantee of that, mail art is in itself a friendly and giving thing.

Whirligig: If you were given a grant for $50,000 to pursue creative work, what would you create?

Jennie: This is every artist’s dream, right? I love to set up some sort of mail art tour throughout the US or Europe, visiting other Networkers and talking to them about their mail art habits/collections/stories/etc. It would be fascinating to document a cross-country journey in some way, either in film or print. Mail art is one of those strange creatures—so many people are creating it, making the community happen, and yet no one seems to know about it. I’d love to remedy that!

Carolee: I’ve become really interested in the idea of collective spaces. I have been eyeing the old Build-A-Bear workshop in my Potrero Hill neighborhood for years, with this grand idea that it would be a fun space to house a combination artists’ workshop/retail store. It can be difficult for people to find the cash to rent an artist’s studio in order to concentrate on their work (let’s face it: at home the laundry always beckons), so I think it would be cool to have a situation where artists could submit proposals to have a small studio there, pay a really nominal fee to cover things like utilities, and to have a built-in storefront/gallery where they could sell their work at affordable prices. It would probably take more than $50,000 to do that, though.

That might not be what you had in mind when you mentioned creative work, but given that I’ve been lucky enough thus far to have the funds to pursue my own interests, I’d like to give other people that chance.

Whirligig: Why do people buy commercially produced products for gifts as opposed to creative, handcrafted, innovative objects?

Jennie: I think it boils down to “having” versus “not having” the time. I know there are plenty of situations in which it is easier to pay the five or ten dollars for some adorable stationery, rather than sit down, break out the art supplies, and create something handmade. Making art means making time—and time is such a valuable commodity for most people.

Another thing is this: often, I purchase items because I love supporting the artist. I want to own a little slice of how they view the world. Someone like Lisa H. of “ilfant press” or Meri B. of “Fixed Orifice Press” embody this idea perfectly; I could never do the things that they do (printmaking, letterpress printing), so it makes more sense to purchase their beautiful products and encourage them to keep on creating.

Carolee: I imagine it largely comes down to access and funds. Handmade items are always more expensive than a mass-produced doodad; there’s also the possibility that people don’t have the access to fairs, galleries, and open-studios situations that we do here in the Bay Area. Not everyone—astonishingly—knows about Etsy and the like.

I also wonder if it doesn’t boil down to gift-giving being a situation fraught with anxiety, where the gift-giver might know little about the recipient and isn’t sure whether the handmade doodad will offend their sensibilities. A lot of people—and I know this is kind of a shocking idea for people like us—still think that the imperfection of a handmade object reflects some kind of lesser quality.

Whirligig: Your merit badges are one of my favorite and I am certain a very popular Pod Post project. How did you come up with this concept and the Pod Post uniform?

Jennie: Well, like many of the items Pod Post sells, Carolee and I came to a realization that if you want something done right, you have to do it yourself. It started as one of those vaguely hair-brained ideas: “hey, wouldn’t it be cool if we designed merit badges for the things that we like to do?” and then quickly evolved from there, due to the positive response we received.

Carolee: We decided (on our first trip to Tokyo) that book arts merit badges would be a really cool idea, started sketching out ideas, and then figured out a way to have them made. The girl-scout/militaristic outfits just followed naturally from that. Sporting a sash requires a more structured and deliberate outfit to support it, you know.

Whirligig: Forty years from now do you envision yourselves still wearing your sashes with merit badges?

Jennie: Nah. It’s a pretty youth-oriented look, so I can’t imagine us working it forever. . .

Carolee: I’m with Jennie. In forty years I plan to be firmly entrenched in my fabulous leather gloves—sumptuous cape—stompy boot phase. Oh, hold on, I’m in that now. :)

I think the look really worked well for us, both from a purely attention-getting standpoint and from a theatrical, accessible standpoint—but I am pretty sure that both of us are ready to try something new, wardrobe-wise. It was fun while it lasted. In retirement, I will have my sash displayed in a two-sided glass case. :)

Whirligig Interview by Nanette Wylde with Kent Manske.

Images from the top: Pod Post Photobooth (Pod Post), Good Mail Day Cover (Pod Post), Pod Box (Von Span), Pod Post Flyer fragment with Mail Art Bento (Pod Post), Pod Post at a Printers’ Fair (Megan Adie), Pod Post Badge (Pod Post), Zines (Pod Post), Kimagura na Dowa no Hon zine cover (Pod Post), Pod Post sashes (Von Span). Courtesy of and copyright of the artists.