Jan Rindfleisch is an artist, educator, writer, curator, and cultural worker. She was the executive director of the Euphrat Museum at De Anza College in Cupertino for 32 years. During that time, Rindfleisch laid the groundwork for an engaged and inclusive museum environment by continuously tapping the diverse local voices of Silicon Valley. Rindfleisch continues her work as a community builder with Roots and Offshoots: Silicon Valley’s Arts Community, a history of the art of the greater South Bay area from the post-Mission era artifacts of the Ohlone peoples to the artists and activists that have made the western/southern half of the Bay Area the rich and vibrant scene it is today.

Rindfleisch has a BA in Physics from Purdue University and an MFA from San José State University. Her awards include: Silicon Valley Business Journal Women of Influence (2014); San José City Hall Exhibits Committee (2006–2013); The ABBY Awards (2010); Silicon Valley Arts & Business Awards; Arts Leadership Award; Santa Clara County Woman of Achievement, (1989); Leadership Vision Award in the Arts, Sunnyvale Chamber of Commerce (1993); Civic Service Award, City of Cupertino, Cultural Arts, and the Asian Heritage Council Arts Award (1988).

Nanette: What was the impetus for you to write this book?

Jan: I am one of those people that love to question boundaries. I started thinking: How did we get past the exclusion in the art world in the monochromatic 1970s, which didn’t reflect the breakthroughs of the 1960s, such as women’s rights and civil rights? How did we take that early cultural landscape, break new ground, and build new forms for the future? After decades as an arts museum director and a lifetime career as an artist, author, community advocate, and educator with an earlier background in the sciences, I decided to put some of the explorations and findings together.

My book and project Roots and Offshoots: Silicon Valley’s Arts Community begins with an essay entitled The Blossoming of Silicon Valley’s Arts Community and a profile of artist/activist Ruth Tunstall Grant. A Spiral Through Time follows threads between the ancestral Muwekma Ohlone, Juana Briones in the 1800s, Marjorie Eaton and her arts colony in the 1900s, and artist Consuelo Jimenez Underwood today. Over a period of years of research and writing, the book grew to about twenty profiles and two additional guest essays; one by Maribel Alvarez about MACLA, “Doing that Latino Art Thing,” and the other by Raj Jayadev about Silicon Valley De-Bug, “The Anatomy of an ‘Un-Organization’.”

There are people in Silicon Valley connected with incredible history, but their story isn’t being told. Their experiences tell a different story of who we are. Origins of organizations are often forgotten or rewritten, and the originators erased. How can one or a few names stand for an organization/period/idea and the rest be forgotten? How does this erasure affect our view of ourselves as creators and as being worthy of judging or promoting art, or taking a larger role in our community? I wanted to add some of these missing pieces that contribute to a richer story of Silicon Valley’s art scene. Frustration with systems can be a motivating force. Another big personal motivation was gratitude. This book is a way to thank so many people who paved the way and with whom I worked.

Nanette: The Bay Area is deeply rich in terms of cultural diversity and creative output. How did you determine which groups to represent, likely knowing that you could not include them all? Who was left out? Will there be a second volume?

Jan: The book is not a survey of the South Bay Area scene. I wanted to tell the story of the trailblazers who truly made a difference in Silicon Valley, and to provide broader historical context for their experience. A major/shared motivator was to share with the reader how the artists/activists in this book enrich us personally. The artists/activists open us to the art of daily life, and to the artist within each of us. They get us to examine ourselves, to question our lives, and to think freely. They inspire us to dream and imagine and effectuate change—to build connections (not walls!) and enliven our communities.

Originally, I meant only to give five examples, with the goal that other people would run with it, write more profiles in the future. Then, as my collaboration with activist editors Nancy Hom and Ann Sherman and other contributors grew, we felt more examples were needed to further the notion of what gets lost when we define things too narrowly. In time, the project became increasingly about context and values.

With respect to what is going on in arts and culture today, borders and gaps persist. Being interdisciplinary is not easy. Follow-up of some sort is needed. It could take a variety of forms, including additional publications that I might write in collaboration with others. There are so many other issues to explore regarding the arts in Silicon Valley, such as mental health, ethnic groups, environment, economic and technological disruption, and aging. We could expand more on women’s struggle, or include divisions within groups, mission creep, co-opting, etc. We need to look at voids, needs, and misconceptions. I would like to connect with others interested in writing such stories, which are not the standard artist stories, bios, art descriptions, critiques, hype. These stories would deal with different and larger life contexts.

As the Roots and Offshoots project advances, options arise in other media—video, interviews, podcasts, and small exhibitions about a person or concept that needs more attention, for example. Future works can address the relationship to advanced scholarship and classes that push boundaries of the academic canon. One can consider the relationship to policymaking and the ongoing education of elected officials, civil servants, for-profit and nonprofit leaders.

The work of Ruth Tunstall Grant is ideal for this. She worked with city and county programs in terms of strategic planning, specific programs, art in public spaces, community celebrations, and social service programs. This was in addition to her impact on the art world, the education world, and the community. Her collaborative art and art of her students from her Santa Clara County Children’s Shelter program are featured in multiple county buildings. She constantly spoke of values.

Ruth passed in June. A couple of her significant contributions to the community include: She developed the first outreach program to the schools via the San José Museum of Art, reaching kids where they lived, choosing schools in impoverished, struggling San José neighborhoods. She started Genesis/A Sanctuary for the Arts in downtown San José this full-of-life studio, art, and music space was housed at three sequential locations that she renovated and developed. The third location later transformed into the current Alameda ArtWorks. With Tunstall Grant’s art on the cover of Roots and Offshoots, the book itself is like a handbook on building communities.

Nanette: What barriers have been broken for the current generation of feminists?

Jan: The recent book and movie Hidden Figures is indicative of the difficulty of breaking barriers. It reminds me of my background in physics and the continuing sexism, racism, and other barriers across disciplines today.

Slowly, our society is distancing from the formerly ubiquitous “his.” There’s more scholarship about women. There are more women in professions. There’s greater understanding of gender. There’s an awareness of cyclical threats posed by adverse socio/economic/political circumstances and the continuing need to address areas where ground is/can be lost. If one looks, one can learn about dilemmas faced and roads we don’t want to go down again, and find words and actions that inspire.

Locally, San José and Santa Clara County had a reputation for being a feminist capital when we had numerous women elected to mayor, city council, and county supervisor positions. Under Mayor Susan Hammer, we had a 10-year cultural plan. We need more women to step forward in the political realms and other areas of leadership, and for them to support other women to strengthen their leadership.

Nanette: Is it important for this generation to acknowledge or even be aware of the work of previous generations?

Jan: We find inspirational support and advice from someone who has “been through it.” Whether it’s for survival or success, it’s helpful to learn from others’ past mistakes, to see how recurring socio/political/economic conditions can disrupt anyone’s path. This knowledge can force us to rethink, reprioritize, and examine our values in relation to others who are also struggling, many times in hidden ways.

Why should an artist care? If you define art, your art community, too narrowly, you will miss out. If you have no interest in civic engagement or building community, you leave these endeavors to others, which may have quite undesirable consequences. Propaganda, including hype of all sorts, is a given. Will it take over? Freedoms are at stake. The arts influence values and policy, directly or indirectly.

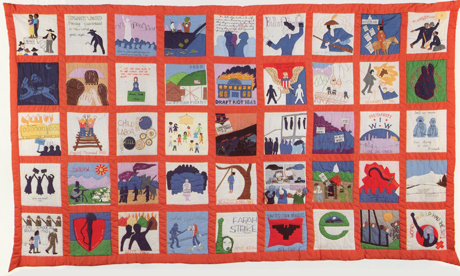

The book was written with many takeaways for this generation. Historian Connie Young Yu wrote of the moral courage of her ancestors who came to this country to build the railroads and asked if she herself would be tested. Through their unusual collaborative quilts and books, Gen Guracar and Connie Young Yu present a challenge to new generations to engage democracy. And people of this generation are taking notice of earlier generations. Recent Stanford graduate Stephanie Gutierrez wrote of the art and activist legacy of José Antonio and Cecilia Preciado Burciaga at Stanford. Another Stanford graduate student, Fanya Becks, has been writing about the Muwekma Ohlone. Recent SJSU graduate student Allison Connor wrote her thesis on artist Juana Alicia, who led and collaborated on major murals in the valley, including a large one for MACLA.

Nanette: Your curatorial practice focused on hearing and representing multiple and diverse voices in an attempt to represent not what we already know and recognize in art, but the larger scope of the local creative community. What were the challenges associated with this level of inclusiveness?

Jan: Advocate Consuelo Santos Killins stated, “The assumption is that quality exists only in highly visible cultural institutions—the truth is an abundance of artistic quality exists in Santa Clara Valley … As in San José, significant progress in the arts will occur when people speak up in order to change attitudes toward art—people who believe in the area they live in.” the same vein, we are accustomed to, and often judged by, providing validity and stature by citing accepted art forms and well-known names and places. I wanted to get beyond traditional and social-media “star/power” systems, and think about meaning, value, and the potential for enlightenment and growth from different sources.

Many people tend to cluster in their own community. I strove to have multiple and diverse voices included. To expand the conversation, you have to take the effort, walk across the street, and talk to them. There are valid concerns about having their community’s voice taken, stolen or exploited. To avoid and/or counter this, I included direct quotations, and collaborated, mentored, dialogued, and reviewed the written material with those close to it to increase my understanding. For publications I asked a diverse group of authors to write large chunks or whole articles. I sought personal responses to areas that resonated with them (or didn’t) and invited feedback/critique.

I also wanted to expand the scope of art to include disciplines that are not traditionally considered part of the “real” artistic practice, such as weaving and sewing. This was a big challenge. Some people need to draw a line around art, and there is a strong resistance to questioning. After years of conditioning, people weren’t always receptive to letting go of long-held notions. Questioning the limits or distinctions can lead to confusion, or one may be dismissed. But pushing these boundaries is important. Consuelo Jimenez Underwood’s example clarifies the benefits of having a larger-scope approach. Through her installations, weavings, threads of many colors, and words, she has made the case for the “Thread Art Warrior.”

Nanette: The exhibitions you curated for the Euphrat never seemed to be focused on you as a curator or as the purveyor of a vision, but rather seemed focused on the celebration of the artists and works which came together thematically. It has been said that when seeking input from others you acted as a sponge, appeared to want the articulation of the exhibition to be community-driven and were extremely open and totally non-controlling. Where does this come from?

Jan: My mother saw many sides to any question or statement. I would think I understood something; then she would offer various viewpoints, put me in other people’s shoes. With her influence, I realized how difficult it was to see a big picture and the importance of asking questions. This realization helped me to stay open to input and not think I had all the answers.

Coming from the sciences, I knew many of us lived in worlds narrowed by income similarities and an abundance of intellectual hierarchies, plus the ever-present racial, ethnic, and gender prejudices. Later in the arts, I saw small areas with more freedoms, but in general the arts were similarly secluded.

At the Euphrat in 1980, I thought we could benefit from more openness and cooperation in the “open door” of a community college. I discussed the idea of a forum concept for exhibitions with many people, including Trudy Reagan. Reagan at that time sought a forum concept for YLEM, the organization she started in 1981, to bring art, science, and technology together.

Our desire at the Euphrat was to get past inherent biases or unsuspected blind spots. We were curious. Through exhibitions, we wanted to learn and collaborate—the crux of education. We wanted to be fair, just. We knew that history and our knowledge base can be self-perpetuating and unjust. “Community-driven” exhibitions would include multiple disciplines from the academic community and go beyond it to include the nonprofit, community, or religious groups that filled a critical need or solved a problem.

We didn’t do theme exhibitions, nor exhibitions with myriad unrelated ideas. Rather, our approach was to select art that challenged and to respect/honor the art and vision of the artists. Exhibition ideas would change in the exhibition development phase. We continually considered a forum context—listening and learning as we went forward. For the exhibition, we would thoughtfully place the art to raise additional questions and bring breadth to all the artwork. Even then, things could change as we received artist and viewer ideas.

Nanette: Who are your role models?

Jan: I am inspired by people who see injustice and do something about it. People like Jane Addams, Sojourner Truth, my parents and grandparents who overcame great odds, friends who survived many difficulties. I respect the people who were there for me and for others, who wanted to help and found new ways to have a meaningful life. I am moved by people who accomplished a lot despite limitations, people who cared enough to help the poor. I value good teachers, especially ones who spoke up and had the courage to build something new, to expand humanity or fix a problem.

In the beginning of my studies, artists Judy Chicago, Judy Baca, Yolanda Lopez, and the Mujeres Muralistas were my role models. I admire many of the trailblazers in my book, like the Burciagas, and women and men who have had courage, caring, and insight to rethink systems. Ruth Tunstall Grant was like a mother to me, giving me words to live by—how to deal with life, what it means to give back joy. “Joy in, joy out.”

Nanette: Who were the Burciagas?

Jan: The Burciagas were a dynamic couple. They helped me out in different ways. Cecilia was a top-ranking administrator at Stanford and Tony was an artist, poet and writer. He was a unique character. They were resident fellows at Casa Zapata at Stanford. I would go over to their dorm—it was very family-like—and we would discuss ideas. They mentored so many people. Their effect is so large.

Tony did very controversial murals. For one, The Last Supper of Chicano Heroes, he asked students who their Chicano heroes were. Then he painted these in a Last Supper setting. As advocates for students, both Burciagas pushed academic boundaries. Cecilia was let go “due to budget cuts.” The students were so upset they held a hunger strike. Some of those students now hold top positions at Stanford. Cecilia told the students, “Don’t do this for me, do it for what you believe in.” She was very community-minded. The students stated their demands and got some of them. One was establishing a Chicano Studies major. Tony died shortly after their leaving Stanford. Cecilia went on to be an outstanding administrator at CSU Monterey Bay. Both gave their all, died too young, yet left a torch-passing legacy.

Nanette: How did the Euphrat start?

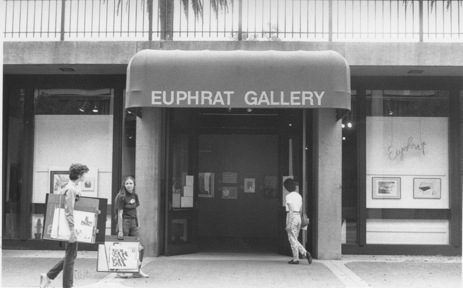

Jan: Way back when De Anza College began, there were the Euphrats, who owned the land. E.F. and Helen Euphrat knew Cal Flint (after whom Flint Center is named). Helen had an art interest and the couple gave an endowment, about $25,000, which started the Helen Euphrat Gallery. After Proposition 13, there was no money to run the gallery. When I was doing my MFA, I decided to have my thesis exhibition there because it was about education. Then, after a while, I started putting together exhibitions and became the “director.” Not a lot of competition with essentially no salary or budget! Only about $500 per show.

Nanette: When was this?

Jan: This was in 1979. I was trying to figure out “how do we make something here?” How do we make it an open door, like the “open door” community colleges are supposed to offer? For many years, the art department and college didn’t want to invest in the gallery—the talk was turning it into a computer lab. I felt if they didn’t have a viable plan and didn’t want to pay, they wouldn’t have much of a say in what we did. I felt we were essentially on our own and needed to create something new. Through those years, till 1985, I taught part time at De Anza, both studio and art history classes. In the standard curriculum, there were hardly any women as creators; rather, they were depicted as objects, often unclothed in the texts. It was a tremendous amount of work to get the art and accomplishments of women and people of color into the curriculum through the years.

Nanette: What made you aware to do that?

Jan: Even when I was a little kid, I could see that it wasn’t fair between boys and girls. I had to wear a skirt to school and I wanted to wear pants like my older brother did so that I could play on the monkey bars. I thought it was cruel that parents and teachers in those days would make girls wear skirts to school. So, it started early.

I grew up near Chicago. My family struggled and became successful. I saw vast income disparities and prejudice. I read a lot of biographies in my elementary school years. An important person was Jane Addams. She ran a settlement house (Hull House) in Chicago where she helped poor people. This started in the late 1800s. She brought in artists and other creative people. She wanted to make a creative community. Another book that influenced me was a children’s book called Twig by Elizabeth Orton Jones, which is about a girl who lives in an inner-city row house and has a barren backyard in which she invents her own world.

Nanette: And this made you think about people who aren’t represented?

Jan: It made me think about poverty, severe poverty.

Nanette: The power of the story.

Jan: I still love that little girl. So at De Anza I decided to make exhibitions about what was meaningful to me and see how long it would take for them to kick me out.

Nanette: At what point did De Anza make you official?

Jan: It was an English instructor, Cy Gulassa, who put in the proposal to get me paid. I remember it was on Friday December 13, 1985 when someone came and rapped on the door of the Euphrat. It was late and dark and they said, “I’m not supposed to tell you this yet, but you’ve got a job. You can’t be a faculty person—there’s not enough money—but you can be a classified person.” So being relegated to classified staff was the beginning of getting my foot in the door. At the time, I thought building Euphrat staff and teamwork was more important than disruptive arguing for my proper faculty position (appropriate after teaching studio and art history for eight years). I stayed with that team approach as a “classified” person trying to bring more people on board till the end.

Nanette: How did the Euphrat really get going?

Jan: As far back as 1980, I felt that the whole community needed to get up to speed in terms of what art is and what students need in art experiences. After I met Kim Bielejec Sanzo, we started building a board. I talked to administrators and trustees of high schools and went to city councils, all the movers and shakers that I could think of, not just in Cupertino, but in Sunnyvale and Los Altos, too. A lot of those people thought that art was something that happened up in San Francisco. They thought it was okay for the sports coaches to teach the art classes in a budget crunch. So I talked to them about why art is important. We did this for a number of years. Finally, there was a shift. I brought trustees onto the Euphrat board from all sectors: elementary schools, high schools, city council people. We would get together and talk about art and what it could do for the community. And we worked on campus across disciplines.

Even at the beginning in 1980, I wanted to build a team. I wanted to empower women. When Kim came along and said she wanted to help, I said, “Okay but we can’t pay you—there’s no money yet. This is a learning thing. We are all going to grow from this.” The first major exhibition/project Staying Visible had a strong focus on women. We got a lot of people together, including students at San José State, who went out and interviewed women in the arts. There were a lot of good articles written and we created a seminal publication on art, archives, and women’s outstanding contributions.

When Patricia Albers came along, we still didn’t have a lot of money, but I told her we could give her a decent hourly salary and I could help her do some things she wanted to do, such as curate and publish. We worked together on the Euphrat becoming a museum. We went through a museum assessment program. She brought a lot of professionalism to the museum. I can’t speak highly enough about her. We did an expansive exhibition and publication on immigration.

Nanette: How did you manage to keep your ego subdued, when you obviously had a vision and produced so many poignant and high quality exhibitions?

Jan: For me, ego must take the back seat. The exhibitions aren’t about me. Many artists have strong visions, not just about their art, but also how to create a better world. When I see the recalcitrance and enormity of the problems the artists/activists faced, I am amazed and want to applaud and support the art and the artist through exhibitions, publications and other avenues.

My exhibitions are very fluid. I am humbled by the insights and creativity people share—whether artists, academics, or community people—and by the energy and generosity of the myriad people who helped me birth the projects, such as editors, designers, mentors, advisors, funders, and more. I love this give-and-take process in conceiving each exhibition, sharing the bumps in the road, discoveries, successes, and even the exhaustion. Each exhibition was created this way, and the book was executed in a similar manner. I couldn’t have written and published the book without my collaborators. They own the project as much as I do. What fun it was when editors Nancy and Ann, book/web designer Samson Wong and I could finally say, “We did it!”

Nanette: How did you come to art?

Jan: I think it all goes back to sibling rivalry. When I was a kid, I couldn’t draw as well as I wanted to so I went into the sciences. But later I came back to art because I wanted to understand it. My dad was a builder and I always wanted to build, so I went into sculpture. When one studies art, we are taught to look at differences and to understand specifics of periods of art. But to what end? To me, the art is something else. In the case of architecture, it is what you do with a space, how you make it livable. It includes what happened before and what happens afterwards. It is not a monument to someone’s ego. But that is the system we are stuck with in academia, and in architecture. We don’t think enough about contributors or after effects—about what happens when we need to tear something down or it outlives its usefulness. We need to start over and rethink the whole thing.

In my thesis work I made this sine-wave, yin-yang coffee table with concrete. It was a male female thing, but it was not functional. You could not put a coffee cup or glass on it. I wanted someone to come along and say, “This is not functional. We are going to have to invent some things to make it functional. We are going to have to play with this for a while to make it functional.” Another thing I made was a playpen with a concrete blanket base. Its fenced sides were half open and half closed. I was thinking about growing up, and whether one is inside or outside, or how much openness one is afforded to ideas and other things.

Nanette: Have you been making art since?

Jan: I think the museum work is art and writing is art. It has just gotten larger and turned into community building. I like to tell people we are all art. Part form, part content. Some of us get up and put on blue jeans and a t-shirt and some of us get dressed up and put on glamorous jewelry. But we are all doing it—form and content—in one way or the other. We are trying to balance ourselves with our surroundings, in our dealings with other people, whether it is via research, creating structures, preparing food and being hospitable, or listening or caring.

Nanette: What are some of the most significant changes in the art world that you have witnessed?

Jan: The art world is not so narrow as it used to be. But it is still very strongly influenced by the art industrial complex. There are cracks of entry, but nowadays it’s more about artists finding new ways of being rather than adapting to the status quo. I focus less on the art-establishment stars and more on the art stars that create works that touch us and make a difference in a community. I am heartened by what I see.

In San Francisco, The Women’s Building is one of the brightest stars in the art world. The multistory exterior, completely covered with the Maestra Peace mural, was painted by a seven-woman team, plus their helpers and volunteers. It’s essential to see and read about. On the national level, the Guerilla Girls position themselves to poke at the art world and raise questions in unusual ways. Asian American Women Artists Association (AAWAA) has a strong, decades-long history of promoting inclusion of Asian American women.

Women from around the Bay Area joined to form WEAD (Women Eco Artists Dialog), which is attuned to the art world, but focused on its environmental mission. Originally an environmental artists’ directory, now it’s an eco arts dialog with magazine, joining environmental and social justice activism. While the Silicon Valley Women’s Caucus for the Arts has merged with its parent, the Northern California Women’s Caucus for the Arts, Silicon Valley women continue to seek new ways to support each other and build coalitions around shared concerns. SJSU professor Robin Lasser and professor emeritus Consuelo Jimenez Underwood are such activists, working separately and together to address issues that interest them.

Nanette: What are some areas that you feel you might be/have been misunderstood?

Jan: Moral and ethical dilemmas can arise when we consider the marginalized. There is always risk involved. If I point out a problem or question an assumption, it’s easy to be labeled, even distanced. If I help one person or a group of people, others may feel left out and think I’m ignoring them or think less of their issues. Seeing one person/group’s problem doesn’t mean I don’t think others have serious problems. We all have something to teach. We all have something to learn.

How far do you stick your neck out? Even my good intentions can be misunderstood. For example, showing 50% women in my early years of museum work elicited substantial criticism, as if I “liked” women better, because it was so unusual for women to be equally shown. I did it because it made sense. Some problems touch me, like an artist or small groups of artists that really struggle to try to bring forward an unfamiliar idea. If I feel I can shed some light, I will try. I leave to others the problems of larger organizations that have big budgets and more ability to rectify them.

Nanette: Tell us about some of your most memorable exhibitions in terms of most successful, most controversial, most challenging, most satisfying. . .

Jan: I don’t measure success by audience attendance or press coverage. My criteria is whether it touched, inspired, or encouraged anyone. I am moved if people felt connected to the work or if the work resonated with them. My greatest joy is knowing someone learned or grew from an artwork/artist/exhibition, then made the effort to learn and understand more and/or follow up with their own art/expression. If s/he is inspired to try something new, to go beyond their comfort zone, to speak the truth and share it, I am happy and satisfied that I’ve achieved my goal.

In some ways, Staying Visible, The Importance of Archives, 1981, is the most controversial of my presentations. It was the project/exhibition/book that started my journey, and its subject matter still resonates. Although we didn’t call attention to it, the artists happened to be all women. Except for one man, the profile articles were written by women. Out of commentaries written by notables in the field, there were more women cited. The project talked about the importance of archives and staying visible in the art world. It seemed the right thing to do at the time. That was when I first worked with artist Marjorie Eaton and her hidden artist colony in the hills of Palo Alto. I also worked with artist Mildred Howard, then quite young, and had a chance to bring the two women together.

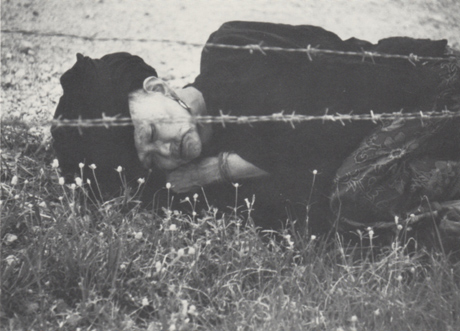

Perhaps the most satisfying exhibition to me was the project/exhibition/book Art of the Refugee Experience (1988), followed by the more expansive Coming Across, Art by Recent Immigrants (1994). Both ring true today. There were 12 million refugees worldwide then; so many more now. Many people have risked all to seek a better life.

For the refugee exhibition, I visited the Phanat Nikhom, Ban Vinai, and Ban Nam Yao refugee camps in Thailand, saw the conditions the adults and children lived under, heard their stories, and viewed the art they made. The exhibition included a range of artists, including art-world artists like Anni Albers and Andrzej Bossak, who restored the paintings and statuary of St. Joseph’s Cathedral in downtown San José in the late 1980s. He had been involved with the trade union Solidarity and fled Poland after the union was crushed in 1981. I remember so well the Saturday night when artist Mao Sith, 19, and his 18-year-old friend created a Cambodian singing kite out of bamboo and tried it out in the courtyard between Euphrat and Flint Center. It was a very heartwarming moment.

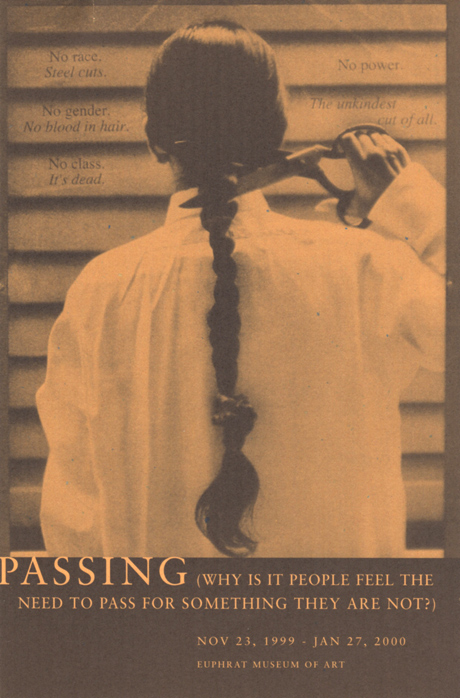

The challenging exhibition Passing continues to fascinate me. Hatched from an idea of artist and co-curator Candi Farlice, Passing examined the activity of passing from a variety of viewpoints, such as race, ethnicity, class, and sexual orientation. When Farlice was a child, she asked her mother, “Why does Hollis only come over at night?” The answer: “Because he’s passing.” While this instance was racial passing, the exhibition addressed multiple forms and reasons—some people passing for advancement, others for survival. Artists and educators participated in the exhibition’s development.

The exhibition focused on the activity of passing for something else, on what is gained and what is lost. Immigrants often drop part of their surname or change it completely. Others pass for other cultures or races. Most of us pass at one time or another. Demographics change when people are “in the closet.” On the personal level, not being the person you are, your life can become a “lie.” From another angle, passing can be connected with becoming, for example, by way of surgery, education, or accumulation of wealth. The art of passing can be a positive life skill.

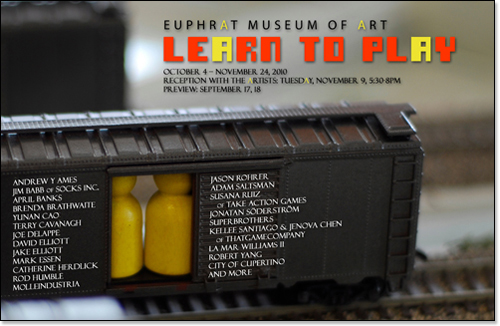

Learn to Play was one of the most successful exhibitions in terms of connecting to a wider community and the scope of the topic. Creating it involved collaborations with key organizations looking to the future of Silicon Valley, an intersection of games, the arts, technology, commerce, and education. There were great discussions working with the main curators, James Morgan and John Bruneau from SJSU. The exhibition itself presents a timeless challenge: When life is a game, how do you learn to play?

Games, an expression of art and life, can bridge the gaps between cultures, and be a common language that brings communities together. Learn to Play included video, board and social games by indie game designers; poetic and artful games, from quick play to epic. The characteristics of these games echo human nature, teaching us who and what we are, or can be, so we can explore life directions driven by our choice and conscience.

The games selected ranged from personal growth to those used for socially conscious purposes. Two women remain in my mind from the exhibition: Brenda Braithwaite and Susana Ruiz. Braithwaite’s provocative games, such as Train, challenge academic learning/knowing about difficult histories. In Help Find Zoe, Susana Ruiz and Take Action Games (TAG) address abusive dating relationships and gender stereotyping in a game for youth, ages 8–14. Silicon Valley De-Bug created a video of Ruiz; in it she speaks of TAG specializing in casual games for change, a new approach to issues, traversing the intersections of computational art, narrative, journalism, activism, ethics, history and documentary.

Everyone enjoyed Yunan Cao’s Ping-Pong Diplomacy, which has an actual, fun-to-play ping-pong table painted with the words “trust” and “distrust” in English and Chinese. The ping-pong paddles had recent faces of U.S./China diplomats, and relate to the U.S. and China in the 1970s (“Friendship first, competition second”).

When I think of the exclusion in the 1900s and the ongoing struggle to reflect the breakthroughs of the 1960s, like women’s rights and civil rights, I am thinking about the section in the book called Getting into the Game. What does any one of us need to grow? To get into the game? To play the game well? Probing these questions may give visibility to the invisible and voice to the voiceless, which is, to me, an essential purpose of art.

Nanette: What was Marjorie Eaton’s hidden artist colony?

Jan: That began with Juana Briones’ house. This was over by Arastradero Road and where José Gorgonio lived. He was Ohlone. He worked with Padre Catala at the mission and then was given the ranch land. He had it for six years and then Juana Briones bought the ranch and developed it. Earlier she developed a cattle and vegetable business in what is now North Beach in San Francisco where the Art Institute is and City Lights [bookstore]. Back then it was known as Juana’s Beach. She was an amazing woman. She was one of these people who could bring together different cultures. She was born near Santa Cruz but her grandparents had come here to escape the racial caste system in Mexico. She was mixed heritage and understood the Indigenous population. She married a soldier at the Presidio, started a business, had children, later divorced, and ultimately bought this ranch in Palo Alto. It was between the city and Santa Cruz, so people would stop and stay there when traveling between the two. She took care of sick people, knew how to stand up for her land rights, was a successful business person and could work with all types of workers on her land. She let Indians stay on her land until she couldn’t protect them anymore. She was a wonderful person who could carve out a space and build on it for herself and others. On her gravestone, it says “She cared.” Talk about an art form.

After she died in 1889, some other people owned the property for about 20 years or so. Then Marjorie Eaton’s mother, who was a fashion designer, bought the land. Her father was a doctor. It’s a long story about Marjorie, but basically, she turns from a Victorian lifestyle into an artist with a bohemian lifestyle. She drives down to Taos to paint for three years, falls in love with a Taos artist; then goes to New York for further art study and lives with Louise Nevelson, with Diego and Frida living upstairs. She helps them financially. She was intending to go to Europe but decides against it because of Hitler [1933], so she goes to paint in Mexico for three years. When she comes back she has an exhibition at the de Young.

Nanette: She was making art too?

Jan: She was a painter. Her paintings of people and landscapes were multilayered—there was something spiritual in them. Although she was very influential in the arts scene here, her paintings were not created in California. She later became an actress. She became a godmother to many children. She had many people living on her property. A mosaic artist, an opera singer, a harlequin, all types of characters, when I visited her there.

Nanette: When was this?

Jan: The early ’80s. I included her in the Staying Visible exhibition. There were very unusual events in this private art colony at the top of the hill. It was fascinating. An inner circle of arts and creativity on a secluded, elevated, otherworldly plane. She helped a lot of people. She was very open but also very private. She knew the right people and the right ways to be connected both in Southern California and here. Her ideas influenced a lot of people. She was part of a group of progressive women who interacted. She had the money and she could play the game.

Nanette: What did you mean when you said, We are trying to cross bridges with art?

Jan: Stanford had the Center for Research on Women (CROW). I worked with them a couple of times because they worked with the Mid-Peninsula YWCA. There was a woman, Hueller Banks, who cleaned houses, but every night she would go home and paint recollections from her past. She exhibited her inventive paintings twice with the YWCA. She was from East Palo Alto. While the communities were segregated, there was an ability with art at that time to bridge these segregated communities, through the YWCA and CROW. In 1979 CROW’s director Diane Middlebrook inspired professor Carl Djerassi to found the Djerassi Resident Artists Program. This was to honor his daughter, artist Pamela Djerassi, who had taken her life the year before. The couple wanted to help women in the arts.

Nanette: Originally it was for women only?

Jan: Yes, because of Djerassi’s daughter. It was initially administered through the art exhibition program of CROW. Later they established a comprehensive program and started accepting men to the residency.

Nanette: What is the most significant thing you think you accomplished at the Euphrat?

Jan: I could say guiding the design and overseeing construction of the new Euphrat Museum prominently facing Stevens Creek. It’s beautiful and versatile, and was a tremendous project to work on. I worked on site and building plans with architects, including architect Mark Cavagnero, and on implementation with the Euphrat Board. The new building was a joy to inaugurate and develop in its first years. This culmination came after we made several earlier attempts to build a more visible Euphrat, starting with De Anza’s founding president.

However, I think the most significant thing is related to content. After three decades, they got used to a different way of having exhibitions—ones that asked questions and worked across disciplines and communities. My goal has always been to increase understanding across disciplines and across sectors. That sounds so antiseptic. But we are divided into silos. It’s a challenge to get the curiosity and the caring and all the other things that motivate us together. There is an economic imbalance that is so huge, educational differences which affect the way we see.

How do we understand and respect the art of another person in terms of what they can contribute? Find something in that. Broaden out more, beyond disciplines and ethnic partitions and country barriers, to all the different parts of us.

Our basic communication is so simple. We know we have this capacity in us because people have pets and they love their pets and don’t expect a million things from them. But with another human being we might be dismissive. We can lose it all in a moment and then what do we have left? Are we still of value? Who are we basically as people? Can we be more comfortable and more sharing of our gifts just by being alive? Helen Jones, director of the Physically Limited Program at De Anza in the early 1980s, stated through a Euphrat exhibition: To deny the right of any person is to deny our own humanity. She strengthened the feeling in me. My mother initiated it, telling me as an adolescent, “Go talk with those old people (our neighbors). What do they have to say?” It makes me think of all the different things we can be or not be. It makes me think of different physical and mental abilities because we can change from one moment to another. How do we understand and value each other? That is what my mother instilled in me and what I in turn pass on to the next generation.

Jan’s Website: janrindfleisch.com

www.gingerpressbooks.com

Bolerium BooksPhotos from the top:

Jan in front of a painting by José Arenas, photo by Kent Manske; Roots and Offshoots book cover image; The People’s Bicentennial Quilt, group quilt coordinated by Gen Pilgrim Guracar, 1976. Appliqued and embroidered cotton and cotton blends, 6’x12′. Courtesy of Needle and Thread Arts Society. Shown in The Power of Cloth; Political Quilts 1845-1986; The original Euphrat, next to Flint Center for the Performing Arts at De Anza College in Cupertino; A good egg by Jan Rindfleisch, evolving sculpture, 18″ x 18″ x 26″, ferroconcrete, landscape bark chips; Niwat Pao-in, untitled color photograph taken in refugee camp Phanat Nikhom in Thailand. Back cover: Art of the Refugee Experience, 1988; MaestraPeace Mural on the Women’s Building in San Francisco; Staying Visible publication cover artwork by Agnes Pelton, Orbits, 1984; Passing exhibition card, 2000; Learn To Play exhibition card, 2010; Ricardo Richey, front window painting for new Euphrat Museum’s second inaugural year exhibition, In Between, The Tension and Attraction of Difference, 2009.