Lisa Hochstein is a Santa Cruz, California-based artist who works in collage, painting and fiber arts.

Lisa Hochstein is a Santa Cruz, California-based artist who works in collage, painting and fiber arts.

She recently curated the exhibition Earth • Science • Art for the R. Blitzer Gallery in Santa Cruz. The exhibition paired 16 scientists from the USGS Pacific Coastal & Marine Science Center with 16 Bay Area and Santa Cruz artists.

Hochstein has a BFA in painting from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Whirligig: What is art?

Lisa: My answer to that depends on whether I am in the role of artist or of audience. As someone who creates objects, art making is a response I have to the world’s bumping up against my awareness. Making art feels very instinctual though I can’t completely explain why I feel drawn to this particular activity. It has always seemed a little strange to me—that awareness leads to a desire to make something. When I am in my studio, my frame of mind is one of openness and curiosity and a certain amount of discontent or unease. Each piece grows from a combination of feelings, ideas, memories, associations and formal considerations, plus elements of chance and luck that I always hope to be awake to. I regain some kind of equilibrium through my work, but it’s not just about that. I also want to be surprised by what I’m doing.

When I’m in the role of audience, I take in someone else’s work and want it to transfer some of that initial response/art-making impulse from its maker to me. As a viewer I also look for something I recognize as much as I look to be surprised. Elegance, honesty, technical skill, originality, narrative truth and aesthetic truth are some of the touchstones for deciding whether I regard something as art or creative output, which strike me as different from each other. There is a lot of creative work that may be artistic but not what I would call art. For me, something that is awkward and raw can be art while something beautiful and harmonious can easily fall into a creative-but-not-art category. Art needs to sing.

When I’m in the role of audience, I take in someone else’s work and want it to transfer some of that initial response/art-making impulse from its maker to me. As a viewer I also look for something I recognize as much as I look to be surprised. Elegance, honesty, technical skill, originality, narrative truth and aesthetic truth are some of the touchstones for deciding whether I regard something as art or creative output, which strike me as different from each other. There is a lot of creative work that may be artistic but not what I would call art. For me, something that is awkward and raw can be art while something beautiful and harmonious can easily fall into a creative-but-not-art category. Art needs to sing.

Once the response takes form and is presented publicly, there is another, broader-based assessment as to whether or not a creative effort qualifies as art. Those assessments are constantly changing and adjusting, so the answer to “what is art” is not singular and not stable. Different audiences in different times and places will arrive at different conclusions about what is or isn’t art. I like the fluidity of these judgements and how things can gain or lose standing as Art.

Whirligig: Why does art matter?

Lisa: It matters differently to different people. The artist, the viewer, the patron, the gallerist, and to our broader culture and social fabric. As an artist it matters to me because I seem to feel better in the world when I’m making stuff than when I’m not. It’s a way of translating my responses to the world into some kind of tangible form. There’s something soothing and reassuring about making that helps me exist in the world in a more comfortable way. Maybe just as an affirmation of my own existence and point of view.

In a social sense, I think art matters because it is an expression of a desire and need to make contact with other humans. It is only through contact and connection—especially with that which feels foreign, other or new—that we develop appreciation and compassion. Art isn’t the only way to do this but it is one that speaks to me.

Whirligig: Is there anything specific about art and art making in our current time, the 2010’s, that you find particularly relevant or important?

Lisa: We live in very strange times. Technology binds us together in astonishing ways, and yet we find ourselves in such a divisive period. The pulling apart is disturbing and I believe that art in all of its different forms can be a counter to that—can be a force that brings us together and makes the Other less threatening. Through viewing and making art we are able to see and show alternate subjective realities that expand individual experience. Art also reminds us that we can only ever see part of a much larger reality.

Sometimes making art in this time and place feels indulgent because there really isn’t a need for more stuff in the world. It’s not that I feel guilt around it exactly, but that at times I wonder how necessary it is. Especially work that uses a lot of resources to be realized. It’s one of the reasons I enjoy working with found, discarded materials and one of the reasons I think there is a trend in contemporary work to do so. To be lower on the materials food chain can ease some of the discomfort—and also be a commentary on—the over-abundance of stuff that’s already here.

Whirligig: I sense that the act of making is significant to your being.

Lisa: To me, the act of shaping and transforming physical materials from one form into another is probably one of the most compelling and mysterious aspects of art making. Both as an act in itself and as metaphor, this alchemy is one of the most amazing experiences. It’s both humbling and empowering at the same time. At a larger scale, it introduces something very positive into a cultural and social dialogue. By that I mean, the process of creating something in the studio is a small-scale experience of creating something in the bigger world—of giving form to an idea.

Actually, I find that making anything is a profound experience. The physical, hands-on engagement connects mind, body, and spirit/inside and outside. As someone who does not embrace any particular religion or spiritual outlook, making art fulfills this part of my being. The contemplation, concentration and focus that is present in most art-making can nurture the kinds of awarenesses typically associated with a religious or spiritual practice.

Whirligig: In these complex times day-to-day existence can be full of distractions and diversions. How do you handle these?

Lisa: My approach to making art requires a slowing down and a consideration of detail that opposes the speeded up, flit-about-on-the-surface distractions that are so characteristic of the larger culture we live in. Stepping away from current technology is a good way to see just how it interferes with our sense of time, place and connection. Turning off the computer or phone, or using a bike instead of a car to get around creates a more immediate experience of the world. I think it’s good to remember now and then that, not so long ago, we weren’t in constant contact with each other and that getting from place to place wasn’t so effortless. While I use and admire much about technology, it is through art and quiet that I remember and return to the things I care most about.

Another potential distraction that is part of being an artist is the commercial and marketing side. I don’t know a single artist who doesn’t in some way find it difficult to reconcile the process of creating with the commodification of the work. Not that this hasn’t existed for generations before, but there is a peculiar tension between drawing on the deepest and sometimes rawest parts of ourselves to make something, and then sticking a price tag on it.

Whirligig: Let’s move in another direction. Your home and studio is in Santa Cruz and you are active in the whole Bay Area.What’s your relationship to place?

Lisa: My relationship to place is a little complicated. Though I grew up in Palo Alto and attended UC Santa Cruz for a few quarters, I never really felt that I belonged in California and I couldn’t wait to leave. I dropped out of college when I was 18 and moved to Western Massachusetts and eventually went back to school, studying art at UMass, Amherst. I remember getting off the bus in Amherst for the very first time and feeling that I was finally home. Which was strange because I had never been to New England before that. When I moved back to California in 2002 I was surprised to find myself here again. Santa Cruz is a good place in many ways, but New England still resonates for me in a way that I don’t think California ever will. Last November I did a one-month residency at the Vermont Studio Center and every single day I was there I savored the unique character of that part of the country, the sense of history and deep sense of place that I look for but never have quite found here.

Lisa: My relationship to place is a little complicated. Though I grew up in Palo Alto and attended UC Santa Cruz for a few quarters, I never really felt that I belonged in California and I couldn’t wait to leave. I dropped out of college when I was 18 and moved to Western Massachusetts and eventually went back to school, studying art at UMass, Amherst. I remember getting off the bus in Amherst for the very first time and feeling that I was finally home. Which was strange because I had never been to New England before that. When I moved back to California in 2002 I was surprised to find myself here again. Santa Cruz is a good place in many ways, but New England still resonates for me in a way that I don’t think California ever will. Last November I did a one-month residency at the Vermont Studio Center and every single day I was there I savored the unique character of that part of the country, the sense of history and deep sense of place that I look for but never have quite found here.

In a funny way, sense of place is very present when I am working as a longing for somewhere else and a disconnect to where I am. Which relates to a kind of nostalgia that shows up, for example, in my choice of materials for collage. Working with found and salvaged material pushes me into reflections on time and history—usually with some amount of wistfulness. But in art, nostalgia can be a trap. Like salt when you are cooking: used sparingly it adds flavor. Too much and the soup becomes inedible.

Whirligig: Your artist’s statement reads,

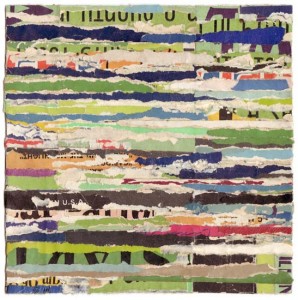

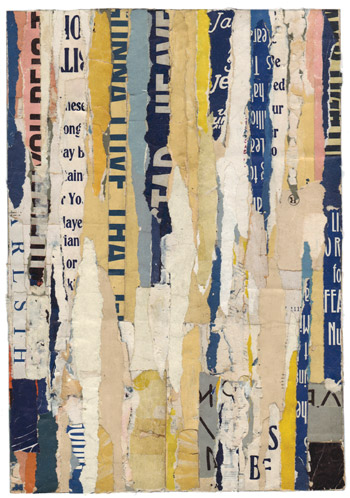

“A collection of sheet music covers from the early-to-mid-1900’s has been the source material for my collage work over the past three years. The colors and typography of an earlier era draw me to this material, as does the pleasure of rummaging through other peoples’ castoffs at flea markets, yard sales, and thrift stores.

“Each finished piece is a layered physical record of its own making, as well as an encounter with the impermanence of objects we at one time hold dear and then later cease to value. My use of vintage material brings the past into a sometimes uneasy relationship with the present, as questions arise about preservation, destruction, and transformation. The finished works range from precise geometric constructions to more fluid, painterly compositions. They resonate with my own intermittent pangs of nostalgia and fuel my curiosity about individual and collective histories.”

I see so much more in your work—spiritual states, the complexities of moods, personalities and relationships, mind maps . . . Take us beyond the statement.

Lisa: What I’ve described in my statement are the aspects of the work that I am most able to articulate. But I’ll try to go further. The things you refer to are the consequences of who I am and how I approach the work rather than intended content. I don’t set out to create, capture, or convey any of these things you alluded to. I think they result from the process and from a formal approach coupled with a what-the-hell attitude of nothing being precious or beyond elimination as I’m working on each piece. I’m pretty uninhibited about destroying what doesn’t work when that’s what’s called for. And it’s in that destruction that things get really interesting for me. I feel a sadness when I need to sacrifice something that’s beautiful for the rest of a piece to work, but the necessity for resolving a piece is more urgent than preserving one particularly satisfying passage. I think most artists can relate to that give and take. It’s what keeps the work honest. When I’m making things I always feel a certain pull towards destruction, which is a big part of my creative process.

I think that who we are is evident in everything we do: how we keep house, how we arrange our lives, how we tell stories. So I would describe my work as conflicted, anxious, and reaching. Those qualities relate to moods, relationships, states of being and, temporarily at least, resolution of a certain kind of discomfort. They also inevitably refer back to issues of loss, preservation, death, and longing. But if I could write or speak eloquently about those things I wouldn’t be making visual art about them.

Whirligig: What are you experiencing during the making process? and after?

Lisa: The actual process is not necessarily an enjoyable one. There are moments of satisfaction and moments of discovery that are magical. But often my experience is one of wrestling with my inability to resolve work. Last fall I got to hear New York painter Judy Glanzman give a talk about her work. She described her process as easiest at the very beginning and at the very end, with a lot of angst in between. That resonated completely with me. But I also think that’s what gives a lot of work its strength—the evidence of the struggle it took to find itself.

Whirligig: Talk more about resolution in any given work. What makes a work resonate to determine if it’s resolved, or finished, or needs to be destroyed?

Lisa: As I’m working on a piece I want to make sure that I have touched and considered every inch of it. Things can happen by accident in a collage or painting, but what remains in a finished piece is there because of intention. Even though some of my decision making around that is analytical, the recognition of something being finished is very visceral. When I look at a piece and nothing annoys me or feels wrong, then it’s done. There are so many moments in the evolution of any individual piece when it can be considered finished but I always want to push past the first few finishes because those are usually the most obvious and least interesting stopping points. I am much more interested in what happens when I work past those early finishes—and that usually forces me to destroy some passages that are quite beautiful. The process builds a kind of confidence that something beautiful will happen again that helps me take more risks in the next piece.

In the collages, part of resolving a piece is not leaving too much legible text. I don’t want viewers to get caught up in reading and trying to find out meanings from words that might be there.

Whirligig: What feedback have others given you that amused, startled, impressed, or agitated you?

Lisa: When people look at my work and say that I seem to be having fun, it’s such a disconnect to me and I alternate between feeling surprised and offended. It’s hard for me to not dismiss everything they might say after that. At the other end of the spectrum though, it impresses me when people I’ve never met spend time with the work and are able to read it in a fully spot-on way. I’ve had people come by during Open Studios and start talking about my collages or paintings and I feel as if they were in there with me while I was making it. I’ve had a couple of people start crying in my studio in response to specific pieces. It’s one of the reasons I think so much of what goes into artists’ statements is unnecessary—especially work that is on the less conceptual end of the spectrum. If the work has a clarity about it and if the viewer spends time, then the meanings should become evident. But there’s a contradiction because I love hearing artists, historians, and critics talk about art. From an audience side, the statement, interview, review, and critique are all things I am hugely interested in.

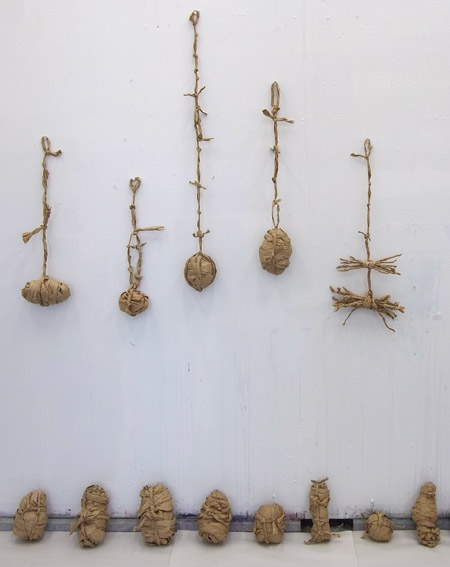

Whirligig: The Paperwork series is a departure from your collage work. When I first saw them in San Jose, I was amazed at how physically dense their presence assumed themselves to be. What about physicality and objectness speaks to you?

Lisa: I love the Paperwork series. I think it was one of those perfect marriages of artist with material and it was so unexpected. I fell in love and I think that’s what came through in those pieces. The physicality of the paper is what those were all about and the act of bundling and wrapping. As objects they feel like a departure from the collages maybe, but the process of making them feels very close. Both emerged from an infatuation with a particular material and both involve tearing and reassembling, which allows me to delve into my obsession with preservation, destruction, and transformation.

Wrapping evokes so many things for me: swaddling cloths, bandages, mummification, and things being secreted away during times of strife. All very visceral and emotional associations. But not what I was thinking about when I was making them. Initially I was just fascinated by the properties of the paper, then by the forms I found myself compulsively making with it. After making a dozen or so, I began to be able to put some words to why they attracted me. Last October, during Open Studios, I showed them for the first time and some of the comments I got from visitors helped me understand why I was making them.

Whirligig: You recently initiated and curated Earth • Science • Art, which I know was a major undertaking on many levels. Would you describe the project and share what inspired you to bring it to fruition?

Lisa: It was my first experience curating a project at that scale. The idea behind it was to create a possibility for collaborations between Santa Cruz and San Francisco Bay Area artists and research scientists who work at the USGS in Santa Cruz. I believe that art and science have much in common and that at certain points they diverge. I loved the idea of inviting individuals from each field together and creating an opportunity for them to explore each others’ worlds. It was a huge undertaking and I’m still excited about expanding and continuing the project. In the next iteration though, I plan to be one of the participating artists.

Whirligig: You spent considerable time pulling this exhibition together which included two receptions, panels and a catalog. What reflections do you have about putting your own art practice on the back burner for a while?

Lisa: For the past six months my work has primarily been about organizing, promoting, and curating. Being in those roles was a way to step outside myself a bit and exercise some different muscles. As an artist I think it’s important to get some perspective and maybe some distance now and then.

While it was a really challenging and valuable experience to put together that project and show, I feel somewhat disoriented about getting back to my own work. Which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, just uncomfortable. Sometimes dormant periods lead to new work that wouldn’t have come about otherwise.

Whirligig: What’s going on in your studio right now?

Lisa: Right now it looks like those pictures you see of Pompeii and the discovered remains. People’s lives just stopped when Mr. Vesuvius erupted. Not much has changed in my studio since January except a little layer of dust has accumulated. It’s time for some cleaning and organizing. Once that’s done I have at least five different projects that I’m restless to get started on. I’ve been doing a bit of writing and sketching about them these past couple of months and am eager to find entry points for each of those projects. Honestly though, I’ve been feeling a little out of sorts, being away from my studio for this long.

Whirligig: What question would you like to be asked?

Lisa: How has your work been changing over the years?

For decades I have been involved with both collage and painting, though for the past few years I’ve done very little painting with a brush and paint. As the collages have become more fluid and more physical, the distinction between painting and collage has become less significant and I often think of the current work simply as paintings. The earlier works from this series were cleaner and included more defined line, pattern, and form—they had a sort of pleasantness to them. My current focus is more on disruption of those elements. Through this process I’ve also noticed that my attention to destruction and preservation has become more pronounced. It’s what has emerged after spending this much time with collage which is, by definition, a process that involves destruction. You said something the other day that captured it really well: that destruction of destruction yields construction.

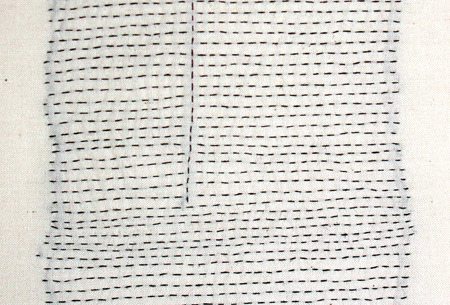

I also have an ongoing series of work involving plain muslin and hand-stitching. About a decade ago I got interested in fabric and quilting, and once I learned some basic sewing techniques, I started creating cloth collages with found fabric and hand stitching. These lead to a very pared down series investigating the simplicity of white muslin and hand stitching. I’m fascinated by the action of sewing in the absence of any functional or decorative purposes. These are my most meditative work and also have a certain obsessiveness about them.

Whirligig: The materials you use are charged with history. Could you talk about that?

Lisa: I’ve always been intrigued by the intersections between individual and collective histories and how our lives are shaped by time and place. Some of the undercurrents in my work are the immigration stories of my grandparents, who came here from Hungary and Russia in the 1920s and 30s. Not that I draw on their lives for specific narratives—those details have been mostly lost. But I do think a lot about the depth of disruption they and others went through, and the courage it took for them to leave everything behind.

My mother’s parents came here from Hungary in the 30s, not knowing at the time that because of that choice they would be among the few members of their families to escape the Holocaust. On the other side of the family, my paternal grandfather was a classically-trained violinist. As a young man he served in the Red Army and after the Polish-Soviet War, he apparently stayed in Poland while the rest of the Army retreated. He eventually made his way to America and had a career that included work as a studio musician, mostly playing viola on recordings for albums and movie soundtracks. It was a job for him—a way to make a living—”but he disliked popular music.

That brief story captures so much about an individual life shaped by huge world events. But it’s not information that I’m trying to make readable in my work. Material that is imbued with somebody else’s history allows me to go there without getting overly involved with the telling of a personal story. Using sheet music from that era (1900s–40s) as source material in my collage work is a way of pointing to that history without getting excessively descriptive about it. A lot of that music was written by Jewish immigrants who came to this country in search of a better life.

Whirligig: Many of your pieces have suggestions of architectural forms or space. Where does that come from?

Lisa: Built environments are so rich and I think the structures that house different parts of our lives are endlessly interesting. Architectural forms are high on my list of creative inspiration. Once in awhile a landscape will speak to me in that way, but I have a weakness for orthogonal lines, right angles, and grids. My first prolonged body of work was based on the Fine Arts Center at UMass—an imposing, modernist, poured concrete structure considered an eyesore by many people. As a student there, I found it to have such character and intrigue, I couldn’t stop drawing, painting, and photographing it. I don’t know if that building created my attraction to architectural space and structure, or if it just resonated with a sensibility that already existed. But it became my muse for several years and I still like going back to visit it when I’m in western Massachusetts. I wonder sometimes if my work would have taken a different direction if I hadn’t encountered that building when I did.

Whirligig: Life and art are like that sometimes.

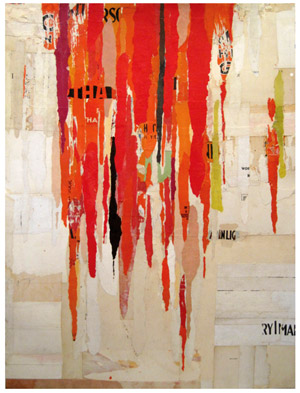

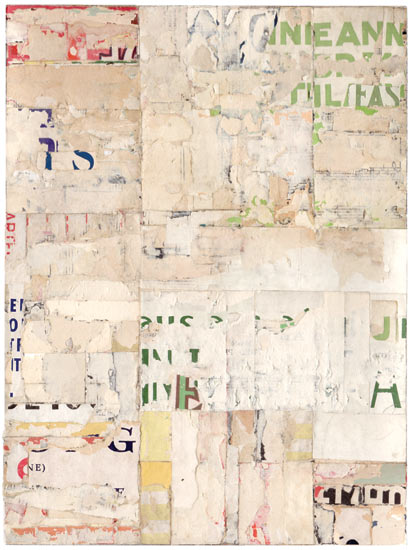

Images from the top: Wrap 2; Origins; Density 3; Unadorned 2; Winter Blue; Synesthesia 5; Parts of Speech 7; Paperwork Installation; Paperwork Installation; Royal Crystal Salt; em•body•ment, detail. All photos courtesy of Lisa Hochstein.