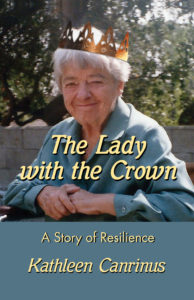

A Tale of Two Remarkable Women: Interview with the author of The Lady with the Crown: A Story of Resilience by Helen Gibbons

Bay Area native Kathleen Canrinus wrote The Lady with the Crown: A Story of Resilience to honor her mother, Dorothy. When Kathleen was 15, her mother suffered a traumatic brain injury in a car accident. After three months in a coma, Dorothy emerged partially paralyzed and cognitively impaired, upending the life of her family.

Kathleen’s memoir focuses on the relationship between mother and daughter, particularly its evolution during the 54 years between Dorothy’s accident and her death at age 99. There were plenty of challenges, but also lots of laughter and, oh, so much love. It’s a story I will enjoy reading again and again, finding some new insight or well-crafted sentence to relish each time.

I met Kathleen in 2006 when we both joined the World Harmony Chorus in Mountain View, California, and our conversations over the years have focused mostly on music. I wanted to learn more about Kathleen’s writing life and in particular The Lady with the Crown. We exchanged some emails and then sat down to talk. Our conversation is edited and condensed.

Helen: When did you start thinking of yourself as a writer?

Kathleen: I came to writing late in life, that is, after I retired from teaching elementary school. When I signed up for my first writing class, I had in mind writing stories from my life and wanted to tell them well. Even though I have now written a book that was published, and numerous personal essays too, I still hesitate to introduce myself to a stranger as a writer. But as far as thinking of myself as a writer, that came in the first few years of writing seriously, when I discovered that I was a person who noticed and remembered things, that I could write an occasional beautiful sentence, that I had a sense of how to shape a story, and most importantly, that finding words to match experience brought with it a thrill like nothing else. Writing lends meaning and purpose to my life. I like the Joan Didion quote: “I write to find out what I’m thinking.”

Helen: How did The Lady with the Crown come to be?

Kathleen: The Lady with the Crown evolved from stories I wrote about my mother over a decade in various writing workshops and classes. My mother had a remarkable attitude about life in spite of epic reversals. She was funny too—good material. I was never writing about her for family alone but for people like my classmates and possible future readers who didn’t know her. I intended to honor her and others who live small lives with dignity and courage. Although I wrote about other topics like friendship, marriage, and aging, the response to the mother stories was the most positive. I planned to string them together in a book and had finished most of them when the editor at a small press offered me a contract.

Helen: What a great opportunity! What happened next?

Kathleen: Next I spent nine months finishing a manuscript. Everything I had already written needed to be revised and new chapters added to complete the story. My editor made a lot of suggestions that improved the book.

Helen: Can you share examples?

Kathleen: When I originally thought about doing a book, I thought I would take the stories I had written about my mother and link them very loosely, like the stories in Olive Kitteridge [a novel by Elizabeth Strout that is a collection of interrelated stories]. I thought that approach would make my task easy. But when I told the editor, she said, “No, no, no! Make it one story. And whether you like it or not,” she added, “you’re the main character. You need to put yourself into this story; you’re not just the witness.”

Helen: Did following her advice make the task harder?

Kathleen: Yes, and it made the book better. Here’s another example: After my father died, my mother had a series of caregivers at her home in Santa Cruz—one bad one after the other. I was living hundreds of miles away in Southern California. I tried to make the arrangement work, but eventually I had to give up and take over. In my first draft, I summed it up briefly, something like, “We had a series of disastrous caregivers, and finally I brought my mother to live with me.” And the editor said, “No, no, you need to put that in scene.”

Helen: “In scene”?

Kathleen: Putting something in scene means that you don’t use a lot of narrative description. Instead, you use images, dialogue, and sensory details to bring the reader into the story. As Nancy Packer [short story author and emerita English professor at Stanford University] puts it, “Make it happen on the page.” So I went back and included phone conversations and moved through the caregiving calamities step by step. It’s harder to write that way. It would have been easier just to say, “That was a tough time.” It wasn’t a time I particularly wanted to re-experience, which is something that happens in the writing.

Helen: What else was going on in your life as you did this work?

Kathleen: The pandemic offered uninterrupted writing time. While I was finishing the book, I stayed active in writing groups, but on Zoom. I also sang world music with our chorus—for a while on Zoom, and then distanced and masked outdoors. I hiked, swam, made sourdough bread, and explored Japanese cuisine. I reread memoirs that, like mine, describe caring for or coping with a severely brain-damaged loved one—Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas, for example, and Family Life by Akhil Sharma. At the end of the summer, I sent my publisher the final draft of the manuscript from Montana where I was visiting my daughter. It took another four months to polish the writing, work out cover and interior designs, and plan publicity, during which time my husband had a knee replacement—a lot to juggle! Getting the word out is an ongoing project.

Helen: Did you read parts of the book to your mother?

Kathleen: No. Because of my mother’s short-term memory problems, I never read any of the book to her. I talked to her about her grandmother though, and early days on College Avenue [the Los Gatos house where Dorothy grew up and Kathleen spent her early years], things she remembered. Several times, I mentioned to her that I was writing about her. “Me?” her shrug and blank expression seemed to say. “Why me?”

Helen: How about other family members?

Kathleen: In general, I’ve kept my writing life mostly private. My family was aware that I was taking writing classes, but I never talked much about them or about writing except to other writers. For years I have thought of myself as a person learning to write, practicing, with nothing quite good enough to share yet. With the book, I had to go public. Before I sent it to the publisher, I read it aloud to one daughter, who is also interested in writing, and she made suggestions. My husband read it after I sent off the manuscript. I didn’t ever mention to family members that I was writing about them because, although they appear, the story is very focused on my mother and me and does not include much about other parts of my life.

Helen: In many of the scenes from your girlhood, you are reading. What are some of the books you enjoyed?

Kathleen: My parents read to me and my brother when we were little—nursery rhymes, fairy tales, and picture books like Make Way for Ducklings and The Golden Egg Book. The book that turned me into a reader is Pam’s Paradise Ranch. I lived my dream life while reading that book. As a girl, I consumed horse books by Walter Farley and others. Nancy Drew was a favorite, Cherry Ames too. I grabbed Boys’ Life magazine before my brother could read it. I also recall reading volumes of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books that were around the house. Later, I enjoyed Louisa May Alcott and the Brontës, Pearl Buck, and Jade Snow Wong. Gone With the Wind was the first book I read through the night to finish, or nearly. I read quite a lot of French literature in high school and college, all forgotten now except for titles.

Helen: What do you read now?

Kathleen: These days I particularly enjoy books by or about people my age—novels like The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes, Out Stealing Horses by Per Petterson, and Meet Me at the Museum by Anne Youngson. I read younger authors too, like Lauren Groff and Curtis Sittenfeld. One of my favorite genres is literary nonfiction—three good examples are The Beak of the Finch, A Civil Action, and The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down. I enjoy many genres—poetry, biography, cookbooks, you name it—and I have read at least a hundred books about writing.

Helen: Who are the authors that have most inspired you?

Kathleen: Certainly the two memoir writers I already mentioned: Abigail Thomas and Akhil Sharma. But if I could write like anyone, it would be Grace Paley. No one can, and that’s what makes her special. She wrote short stories that came directly from her life. “Wants” is my favorite short story by Paley.

Helen: What have you written besides The Lady with the Crown, and what are you working on now?

Kathleen: In addition to the memoir, I have published about a dozen essays—two since the memoir came out—and a book review. I wrote a poem about my father right after I finished the memoir. It’s hard to write about him because I can’t see his faults, I can’t see him really as human. After my mother’s accident, he stayed with her—he did all the cooking, he did the caregiving, he did everything. He didn’t complain, and he didn’t ever talk about his life being hard. He just carried on. I have always admired him for the choices that he made, and I want to write more about him. Meanwhile, I have three short stories underway. Fiction is harder for me than memoir, but it interests me and is a nice change.

Helen: Has writing become central to your life?

Kathleen: It has. The creativity of writing thrills me. Starting with a blank page and making something—it’s so different from anything else I have ever done. I loved collaborative teaching, but something about the non-collaborative aspect of writing, being on my own, appeals to me. From nothing to something, and I did it!

Helen: Do you have any advice for aspiring memoir writers?

Kathleen: Read. Read memoirs especially. And take a class. In a class, not only will you learn what to do and what to avoid when writing, but you will read great stories, both by published authors and by classmates. The first class I took was through a Bernard Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. In this class, an English woman who had worked at Bletchley Park [an Allied code-breaking center during World War II] sat next to a German woman who had survived Kristallnacht [a violent attack on Jews and Jewish-owned stores, buildings, and synagogues throughout Nazi Germany in 1938]. Both were terrific writers with compelling stories. Another classmate grew up poor in Hungary, came to this country, started a company, and invented a computer language. From other students, I learned what it was like to grow up in Iran and Holland, Michigan, and on a farm. If you don’t think you can remember enough to write about, try this: Imagine yourself in the home you grew up in or spent years of your childhood in. Walk through the rooms. I’ll bet you can even draw a floor plan. Open drawers. Listen for sounds like the front door closing. Add family members if you like.

Helen: Did writing The Lady with the Crown help you process some of the trauma of your mother’s accident?

Kathleen: The answer to that is two-fold: “That’s not why I wrote it,” and “Yes, in a sense it did.” I wrote my memoir to share my remarkable mother. I included the dark parts like facing and owning up to a few unpleasant truths about myself to render the complete story and so others with similar experiences would know they are not alone. What’s true also is that the process of writing about this trauma, turning the chaos of experience—in my case a random tragic accident and its fallout—into a story with a beginning, middle, and end, giving the story shape and meaning made a difference in the way I hold the memories. I feel lighter. This is a therapeutic effect of the writing process. But for the record, no goal, whether freeing yourself, healing yourself, or even honoring a beloved mother excuses a writer from the hard work of making art. Writing about personal experiences is not easier than other kinds of writing. Good storytelling of any kind involves doing research, creating a narrative arc, and using all the elements of craft—dialogue, scene, and description—to bring the pages to life.

Helen: The Lady with the Crown was released in January of this year. What kind of feedback have you received?

Kathleen: The book has gotten good reviews, online and at readings. The feedback is extremely gratifying because the book has touched people. Every couple of weeks I get an email from someone who has just read it. Often, they have their own story, of placing a parent in a memory unit or caring for a mother who became ill when they were young. There are very few people whose lives have not been touched by something like this.

You can order The Lady with the Crown: A Story of Resilience from independent booksellers everywhere. It’s also available at public libraries in Palo Alto, Los Altos, and Los Gatos.

Kathleen Canrinus enjoys attending book clubs in person and on Zoom to participate in conversations about The Lady with the Crown. Contact her at: theladywiththecrown at gmail dot com

Helen Gibbons worked for many years as a science writer and editor in the U.S. Geological Survey’s Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center. Highlights included blogging from an icebreaker in the Arctic Ocean and editing the newsletter Sound Waves. Now retired, she enjoys reading, singing, walking, and writing an occasional article as a USGS volunteer.