A Richard Whittaker Conversation

A few years back, Sam Bower and a few friends would gather every few weeks to think about the future of Bower’s greenmuseum.org. Its funding had come to an end. Was there some meaningful to way to keep it going?

I’d happened into this group about that time and it’s how I met Zach Pine. Although we never managed to come up with a saving strategy, it was always a special pleasure meeting with this group of creative dynamos. Our meetings would begin with a silent meditation and move on to brainstorming as Sam manned a whiteboard, sharpie in hand. After a few hours, we’d share some food. Our meetings went on for three or four years. In the meantime, occasionally I’d run into Zach at Karma Kitchen in Berkeley. Even so, I didn’t know a lot about him. He’d mentioned that he was involved with contact improvisational dance and had also been doing some art activities in nature with groups of people.

One day I began asking questions and soon learned that he’d been a doctor before I met him. I was stunned. It was hard for me to imagine that this open, lively, youthful and entirely unpretentious man had already been a medical doctor and had left the profession. But so it was. Later, I got a good look at his art. The time had come to ask for an interview.

Richard: Let’s start with your journey into medical school and your experience there.

Zach: I went into medical school for a lot of the reasons that I live life the way I do now. I was really interested in caring for people. I was very curious and had a scientific mindset. I wanted to get at real human things, and health and health crises were something I experienced up close as a young man.

Richard: Can you say a little bit about that?

Zach: My girlfriend got quite ill right after I met her in college. Now we’re married. I had a lot of experiences with the medical field because of that. I saw the science and humanity in it and, at that point, I decided to go premed in college. Before that I was an English and Physics major, so I already had diverse interests. My father and my stepfather were both experimental physicists. My mother is a painter, and also went to the High School of Music & Art in New York City, and did a lot of drama work.

Richard: You lived in New York then?

Zach: I did, but not as a child. I actually grew up in California with my mom. My parents divorced when I was two.

Richard: Both your father and stepfather were experimental physicists. What does that mean, exactly?

Zach: In the world of physics, there are two main branches, experimental and theoretical. The experimental physicists are the ones who actually design the experiments to try to find out how things work. My father and stepfather both worked on all the atom smashers here in the U.S.

My youth was spent, in the summers, going wherever my dad was doing experiments. He would go and experiment with something that took months to run. Stanford, Brookhaven National Laboratory, those are places that we went because there were accelerators there. So I was interested in physics and in the humanities in college. I realized that medicine actually combined a lot of the things I was interested in, and I had personal experience with what it felt like to be on the receiving end of medical care. I saw there was so much opportunity for ways of being creative in delivering care and, also, understanding medical problems. That was how I got interested in medicine.

Richard: Then you ended up going to Amherst where you met your wife. And now you’ve just celebrated 40 years from your first date, and have been together ever since?

Zach: Yes.

Richard: That’s really lovely. How long did it take for her to get back to health, more or less?

Zach: More or less is an important term, because her illness allowed her to come back to college and graduate a year after I did. It was a period of several years for treatment. It was very intense. I think going through that is part of what bound us early on, and we stuck it out with each other. I have a caring nature, and I think my wife saw that I would, and could, be caring, even as an 18-year-old, which not all 18-year-old guys are.

A lot happened in medical school and medical practice. A lot of things that are still influencing me. I pursued an academic career, so I was doing research.

Richard: An academic career connected with medical practice?

Zach: I became an academic physician, which means you stay affiliated with the university. The traditional trifecta of academic medicine is research, teaching, and practice. I enjoyed all of those things very much and had an affinity for all of them. But also, from the beginning of medical school, I felt at odds with the profession. I felt like traditional medicine and traditional medical education were really harmful to people in the profession—trainees, faculty and also patients. Despite all the caring that was being done, there was a lot of unnecessary pain.

Richard: I’ve heard some people who went through medical school talk about the trauma of it. It sounded like it could be kind of brutal.

Zach: It was. And in my day, it was already better than it had been in the past. Now I hear it’s better than it was in my day. But it’s still no piece of cake.

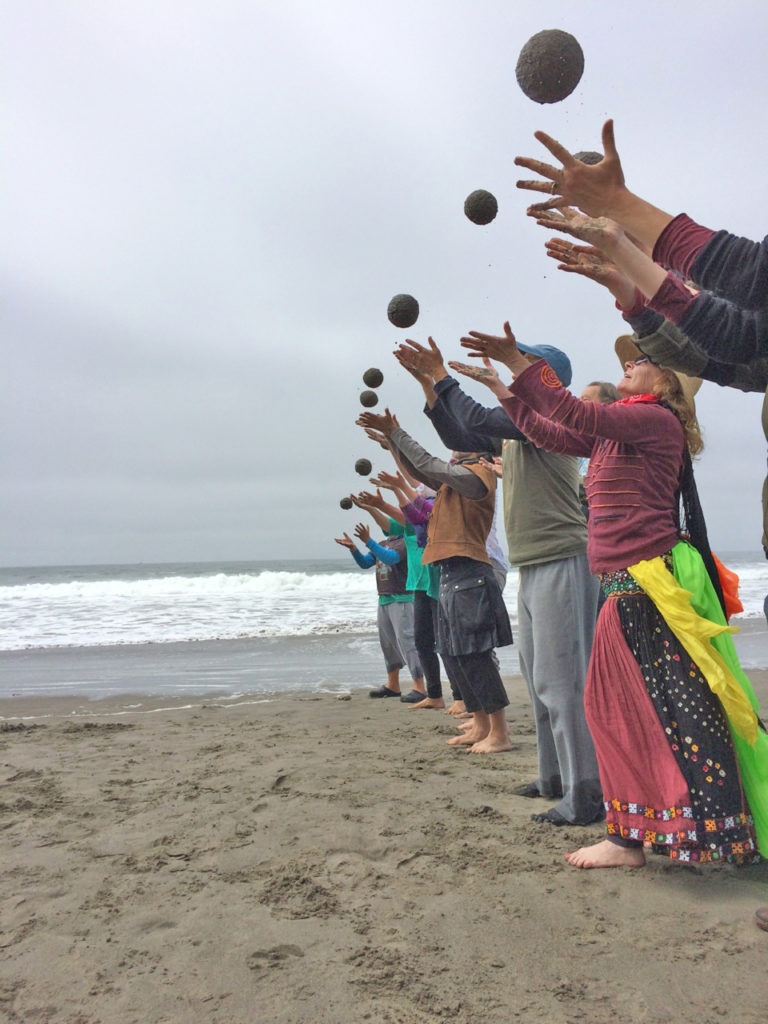

Photo: Marco Sanchez

Richard: One friend said, “It almost killed me.” That sounds like hyperbole, but he almost literally meant that. Would you like to say anything about some of the things you found to be problematic?

Zach: I can’t speak to how things are right now; I graduated from medical school in 1986. There’s a way that the educational process is exploitive. It uses the labor of the students and doctors-in-training to work very long hours and to do a lot of tasks that are unpleasant. That felt awful to me sometimes; I felt exploited, but also, there wasn’t enough focus on patients as humans.

It was the beginning, really, when I was there, of the realization that that was a defect in medical education. There were institutions, including Columbia where I was, that established curricula and approaches to try to help doctors-in-training learn to see their patients as people, not just as collections of organs. But those efforts weren’t enough at the time. For someone like me, who wanted to see patients as people, there was always a lot of tension and, sometimes, conflict with the system.

A perfect example, and it’s very simple, is when I was in residency training, again at Columbia. I studied rehabilitation medicine, so that was my field. I was in the rehabilitation clinic and we had to see a certain number of patients in a certain amount of time. The clinic managers wanted you to get them out quick, you know, like a factory. A complaint that many patients have had about their physicians over the years is that they don’t feel listened to, they feel rushed, and that just wasn’t natural to me. You can’t approach proper care of people that way.

Richard: Listening to you, I get that you have a strong enough connection with your essential humanity that you couldn’t accept this abrogation of the doctor-patient relationship that was taking place. You just couldn’t push it far enough out of your life.

Zach: Exactly. And it created tension with the system. But it also created great allies, because there were other people there who felt like I did. The clinic staff would do things like give me the special patients, the ones who were “difficult.” They would give them to me knowing that I’d take the time. Then they would, basically, buffer me from my higher-ups, the physicians supervising me. They would say, “Well, we gave Zach that difficult patient, so he needs extra time.”

Richard: That’s great.

Zach: I had allies who saw what I was doing. Both medical school and residency were really formative experiences for me; I really loved what I was doing. I was happy to choose rehabilitation medicine as a specialty, because at that time, it was one of the first specialties that did try to treat patients as whole people. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, or PM&R, is still a specialty. It’s quite small, and has to do with taking care of people with disabling conditions. So, when you’re talking about rehabilitation, you’re talking about how can the person function best in their role in society, as they wish. That includes their work, play, family relationships, ability to take care of themselves, sexuality. It’s all in there. I was really glad there was such a field. It was a good choice for me because of my humanistic tendencies.

Richard: I’ve interviewed a few doctors, and I think our whole health care system is out of whack. So I’m glad we’re talking about this. I read somewhere lately, that there’s a fairly high suicide rate among doctors. I imagine doctors must suffer because they’re not allowed to really engage in the human part of care, given the bottomline priority in medical care today. The doctors must suffer and it can’t be good for patients, either.

Zach: I think that’s right. The other thing I really learned through the rehabilitation medicine work I did is teamwork. Unlike in other fields, there’s an established culture of working together as a team, including the patient. There’s the patient, the doctor, and then all these other people who are professionals: nursing staff, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, psychologists, vocational therapists, prosthetics and orthotics professionals. All those people can come together and have a meeting, including the patient, to decide questions of what are we going to do, and how?

In my current work, I’m doing a lot of things in groups, and also a lot of improvisation. Improvisation has been really important as a principle for me in more recent years. But even back then, when you treat patients as people, that’s always improvisational, because no two people are the same. You use the resources you have and do the best you can. But in the medical field you’d never write in a chart, “We’re improvising with this patient.” That would not go over well.

But really, that’s what science is, too. You have a hypothesis: if I do this, will it help? You have a feedback loop: actually that didn’t help, so we’ll have to improvise something else. The idea of necessity being the mother of invention, which is really what improvisation is, has to be done in order to take care of people. I think the seeds of that were planted early on for me.

Richard: Fascinating. Why did you leave the medical profession?

Zach: Well, I’d been making art in nature since I was a kid. I grew up in Northern California. My mom saw how much I loved being out in nature. She took me to the beach a lot, and I’d make sandcastles that became, essentially, sculptures. That became my way of relating to nature, getting my hands on it and actually investigating it. It was scientific and it was artistic from the beginning.

Richard: What was the scientific part?

Zach: At the beach, understanding how the tides and waves work, and understanding how sand is, as a material.

Richard: Where do you think that interest came from?

Zach: I was one of those annoying kids who always was asking the “why” questions. I think the science and art were bound up in each other from the beginning, as they still are for me. Every time I was in nature, I’d make things with materials I found, and I did it as a way of connecting to the place and learning about things. I moved back to Northern California with my wife in 1998 from the East Coast.

Richard: Did moving to California also mean leaving the medical profession?

Zach: Not yet. I got myself a two-year research fellowship at UCSF in the Department of Geriatrics. I was interested in subjective measurements of disability, how people report on their own daily functioning. UCSF was very interested in that. So I came out here and halfway through that fellowship, my stepfather died unexpectedly. I was having a lot of struggles with the slow pace of what I was doing professionally, and I was doing more and more art in nature on my own. People started coming up to me while I was creating things and asking, “What are you doing?” On impulse, I’d say, “Well, I’m putting sticks on this rock. Do you want to join in?” Very often, people would.

I realized there was something really special about the connection of working together in nature, working in collaboration. The seeds of that were planted at the same time I had this crisis of my stepfather’s unexpected death. I had a year to go on my fellowship and I decided that when the fellowship ended, I’d leave medicine and go into art full time.

Richard: That speaks very powerfully of the depth of your connection with whatever was going on with you out there making art in nature.

Zach: Oh, yeah. I turned to it as a way of coping with daily life. The kind of art I make with natural materials is ephemeral. Life and death are right out there when you make ephemeral art. You have to be attached to it and love doing it, and you have to be ready to let go of it.

People say they have a meditation practice. They use the word “practice” to mean that they do it on a regular basis. I think of my art as practice, literally, for living. I don’t draw a bright line between my art practice and my life practice.

Richard: That’s wonderful. It’s a terrible thing to think of art and life as separate, and to think that there’s a class of people called “artists,” while the rest of us are just regular people. I think of this wonderful artist, Joseph Beuys. I use a quote of his a lot, “all people are artists.” And all of us have, as you know, a creative function. It applies everywhere, but the culture sort of puts creativity in the “art” box. Like you said, it’s an improvisation when you’re dealing with a patient.

Zach: Exactly.

Richard: What you’re saying reflects an appreciation for that broad reality.

Zach: I have a huge connection to Joseph Beuys’ philosophy of art! I discovered him around 2000. I met Sam Bower, and there was an article on the greenmuseum.org website about Beuys. Reading the article, I realized, “Oh, my gosh, this is what I believe! I believe everyone is an artist.” Also there’s Beuys’ idea of social sculpture, that the medium for art can be people and places. There’s a way in which we mold society by our actions.

In my artist’s statement on my own website, I have only one hyperlink, it’s to the Social Sculpture Research Unit, which is a Joseph Beuys inspired place. So, you’re definitely hearing what I’m saying about how important that is to me.

Richard: Well, I’m on board with you!

Zach: What you say about the boxes of artists and nonartists, I face this all the time, and I have some tricks for dealing with it. A lot of times I don’t use the word “art” to describe what I’m doing, because people have already decided that they’re not in that box.

I do a lot of free public events where I invite people to come together and create together. I might say “create together,” or I might say “make stuff” if it’s kids. I might say, “Come make stuff with me.” Someone will ask, “Hey, what are you doing?” I’ll say, “We’re making stuff out of nature; come make stuff with us.”

For a certain type of audience, I need to avoid using the word “art” because it’s very off-putting. On the other side of the coin, sometimes I need to emphasize the word “art” to get legitimacy. Like, “I’m not just playing in the sand. This is actually an artistic endeavor.” So, yes, the language I use recognizes those boxes that people feel so strongly about.

Richard: That’s very skillful. One of the things that interests me is how there’s a bias in the Fine Arts against the idea that art is therapeutic or that you would ever speak of your own practice as a therapy, and that seems sort of mixed up.

Zach: Right. It flies in the face of all the evidence, including all of the artists who clearly are getting therapy from their art, even if they won’t admit they are.

Richard: What is the therapy in art making, anyway? Do you want to give a definition?

Zach: I don’t have a good definition for therapy. I’m not an art therapist, by any means. But I am a healer. I believe that everyone, really, is a healer just like everyone is an artist. I think the underappreciated part of therapy is actually not fixing something, but strengthening something, galvanizing people, building resiliency.

Of course, in rehabilitation medicine, a lot of things can’t be fixed. If a person has a stroke, they may have an arm that’s paralyzed for the rest of their life. You don’t fix that, but you strengthen the person so they can do things, despite having an arm that doesn’t work. I do know an art practice is something that helps you live your life fully, and cope, and be strong.

Richard: That’s beautiful. I don’t have a good definition, either. I think it would be something that brings you more fully into life. What interests does your wife have?

Zach: When I met Rachel in college, she was an art history major. She knew a lot more about art than I did, and she may still know more, in a traditional sense. Now she’s associate editor for the magazine Edible East Bay.

Richard: In regard to art, I was looking at some of your early work. It’s wonderful.

Zach: Thank you. The work you’re referring to is what I call solo work. For about five years, I took photos of the work; it was actually because of Rachel that I started doing that. Others had told me the same thing. I’d always say, “I can’t take a picture of this because it would spoil my process.” I had a fear that thinking about taking a picture would spoil something that’s so important to me. So I resisted that for a long time.

But my wife is very persuasive. She told me my work was beautiful and that it would inspire others. I’d also just started working with groups, and she said, “If you want people to come do something with you, you need to establish that you’re a legit person, and having photos of these beautiful things is going to help you do that.” Then she said, “You could put your camera in your bag and forget it, and just do your work. Then at the end, you could remember, ‘Oh, I have my camera,’ and then take some photos.”

I was surprised at how well I could actually forget. At the time, I was interested in making things that looked beautiful. So, I learned how to take pictures and also learned a little bit about the art world, like you could exhibit your photos, you could sell them, and I did all those things. Everything my wife said was true and turned out to be a really important, useful stage in this journey.

At some point, I lost interest in making beautiful things on my own. I kept making things, but my interest was so far away from things that were going to look beautiful, it seemed like taking photos didn’t make sense. It sort of petered out after that. But recently, I’ve started taking pictures of solo work again because I want the sand globes I’m making now to look beautiful.

Richard: That’s so interesting, your sensitivity to your process and the concern that maybe taking pictures would threaten the integrity of it. I’m touched by that. I’d call that virtuous. We don’t use that word much today, maybe because it sounds priggish. But the deeper meaning of virtue is something so needed today, and guarding the integrity of your process was more important than making an outer profit.

Zach: I felt that very strongly then, and still feel it now. I do a lot of group things, and I also do teaching and training. I set up places where people can create with natural materials. In all the things I do, I’m aware of that same feeling I had back then: Am I doing the right thing? Am I doing this the right way?

I’m glad I have the time and luxury to be able to do that. I’m not in academic medicine where, if I asked whether I was doing the right thing and the answer was no, my boss would still say, “But you have to do it anyway.” And since I’m my own boss, I can decide to do the right thing.

Richard: Well, what you just said should be underlined. It seems that this idea of doing the right thing is so important, and so missing, not because people inherently don’t have it in themselves somewhere in their hearts, but because the pressures of life; the prevalence of lies; the scramble to get ahead, to cut corners, etc., make it almost impossible to hold out for what is gained by adhering to a kind of authenticity.

Zach: It’s interesting, and thank you for bringing this idea up, because I haven’t thought about it in relation to how I work with groups, and especially with children. I do a lot of work with children, and a lot of it is informed by this idea of social and emotional learning, which are catchwords for what children don’t learn in school: how to communicate with each other and how to, in essence, do the right thing by the group and by each other, not just for themselves.

This collaborative art making is a great vehicle for that because it’s new. It’s a new challenge for, say, a group of children. They haven’t done it before, and there are fewer of those preconceived notions about who’s the expert, who’s the bully, who’s the prettiest, who’s the best dancer, who’s the best dresser, and all the ways kids judge themselves and each other, or who’s the artist and who’s not the artist. For that, I take the word “art” out of it, and just say we’re going to “make stuff” together.

But the idea of doing the right thing by each other, not just for yourself, is something I really try to convey. It really is one of the underlying themes in a lot of my work now, and has to do not just with opportunities to be creative, but opportunities to be together in the right way.

Richard: That’s beautiful. You were avoiding worrying about branding yourself, turning yourself into a cottage industry, I’m touched by that. I just feel that you’re on the right side of the fence here.

Zach: I feel that way. Now I’m also in this unusual situation of having to market, some of what I’m doing. I’m following the lead of our societal tide in some ways, like I have an lnstagram account and I use a hashtag, #sandglobes, because I want sand globes to go worldwide and become like a fad.

If I were selling Coca Cola, I probably would be taking some of these same steps I’m taking now. But of course, I’m not in it for the profit. I’m in it because I feel that if making sand globes could become a worldwide fad, people would go to the beach more, they’d touch the earth and they’d work together to make beautiful things. They would see their agency in shaping things; they’d see the value of shaping and protecting the coastal areas from global warming impacts, and from sand mining and pollution.

These are very high aspirations for the simple act of basically making a sandcastle in the air, which is what a sand globe is. You make it by throwing it in the air. But that’s what gets me fired up. That’s why I feel like I have to go on lnstagram, because I’ve got to follow the tide of what’s going on a little bit while, at the same time, trying literally to stop the tide from getting too high at those beaches.

Richard: I think it’s fair. We have to try to enter the world.

Zach: I still make solo work with sticks and leaves and mud, and stuff. I usually go to Redwood Regional Park. I have a permanent space up there for creating with nature.

Richard: A permanent space? What do you mean?

Zach: Since 2010 I’ve worked with a group called Samavesha, a local nonprofit. I started working with them on their Art in Nature Festival in Redwood Regional Park. We did it for four years and each year the number of people doubled. It started with a thousand. So, by the last year, it was eight thousand people. Then, we decided to go on hold for a while. We worked with the Park District closely the last year and couldn’t come up with a model that would be sustainable, at least not yet. It’s a long way of saying that as part of working on this festival, we set aside an area for creating with nature.

After the first festival, I proposed to the then supervisor of the park, Dee Rosario, and ranger Pamela Beitz, that we make it permanent and use it as a way of protecting a restoration area. There’s an area being restored under the redwoods. Since 2010, it’s been permanent. I go up there pretty much once a week, check up on things, and make art myself. One of my ongoing collaborations is with the Park District.

Richard: That’s interesting. Beauty is really an interesting subject, and an interesting question.

Zach: It is. I read this book, Art as Experience. A lot of it is about aesthetics. It’s like so many other important things, like love. We can talk about it a lot, but it’s really hard to put your finger on it. When I used the word “beauty” in relation to those solo works I was making, I was looking at them as something I wanted to look at. That was the type of beauty I was talking about. Now, there are other forms of beauty, like the beautiful feelings we have when we dance together, or when you have certain sensations, or you hear beautiful music.

But wanting to make something that when others saw it, they would say, “Hey, that looks beautiful, or inspiring, or at least interesting,” that’s what brought me back to taking pictures of my solo work. So now, in addition to going to Redwood Park and working with leaves, and sticks, and mud, I’m going to the beach and making sand globes. And I’m interested in the lighting, especially at sunset, when the globe is illuminated from the side; it looks so planetary. Or when it’s balanced in a precarious way, or when the ocean or the Golden Gate Bridge are in the background. Or when there are people and dogs in the background. There are interesting visual juxtapositions between the stability of the inorganic form of a sphere, and then of humanity, or the animal vitality of the dogs. I’m interested in that visual experience for myself again.

At the same time, just like back then, there was this confluence. This time, I’m realizing, “Oh, these are pictures I can use to further my goal of spreading these sand globes worldwide.” So, I post them on social media. I’m not making prints and selling them.

Richard: I saw some of those photos on your website. They’re magical things. Even though I haven’t made one, I already know that the process of making a sand globe is a physical, embodied experience. I’m interested in what you might have to say about this physical part of it all, the experience of embodiment. It must be important for you, the embodied life, because you have a whole dance kind of history we haven’t even touched on. But I don’t want to put words in your mouth.

Zach: Just in relationship between what you call embodiment and my own dancing practice, and I say dancing “practice” like I said “art practice.” A lot of the dancing I’m doing has the same impetus and the same results as the ephemeral art making. Moving in space is essentially making ephemeral art; you’re making a trace in your own experience. It’s like an internal movie, a sense movie of an experience. It can feel beautiful, or painful, and it can feel different ways just like any movie can. But there’s a strong relationship. I’ve actually included a lot of dance and movement art with my ephemeral art making, with physical things from nature, always reminding people that humans are nature.

In a couple of weeks, I’ll be collaborating with a dancer. We’ll be treating found objects from nature, found objects that are manmade, like cement and other things we find out there, and our own bodies, all equally as materials, making

sculptures and making movements together.

I tend to blur the line between creating with nature and creating with my body, since I am nature. Sand globe making is especially physical. You literally throw the sand in the air to make a sphere. When the wet sand is weightless, it liquefies and tends to form a sphere on its own. Tossing the sand in the air is basically assisting a natural, physical process. It’s also part of why I see it as a powerful vehicle for this connection with nature in coastal areas. Humans have an innate need to connect with nature. It’s the same with their bodies. People have a natural need to be connected with their bodies. So many people sit at the desk all day and don’t get enjoyment from their bodies. Moving to make a sand globe with a group, tossing it back and forth, feeling the rhythm, feels like you’re dancing with someone, and everyone knows how great dancing is for you.

Richard: Tell me what’s going on just holding that wet sand in your hands.

Zach: When I’m out alone at the beach and I scoop up the sand in my hands, that’s one magical kind of connection. It’s like tasting a food you’ve never tasted. You have no idea what to expect, all you know is it’s food. You might think sand is just sand, but this is not the way I experience it. If I pick up sand at a beach I’ve never been at, right away I get all kinds of experiences: what the grains are like, what the color is like, what the proportion of water is in it, and even the scent of it sometimes. All those things influence my ability to make a sand globe out of the sand I’m holding.

Richard: It’s a rich experience through the senses and you used the word “food.” The experience is like a food. So say something about the food part.

Zach: Thank you for noticing that. That came unconsciously as an analogy, but that’s what it feels like. It feels very nourishing. It feels like there’s an innate need. Just like when you’re hungry, you eat; when you’re thirsty, you drink. When you need to touch nature, what’s a word for that? A lot of people maybe don’t even recognize they have that need.

There’s a form of sensation called interoception. It’s like being able to sense what’s inside your body, like I’m hungry or I’m cold. Some people are really interoceptive; they know how they feel inside. Other people are oblivious. They’ll say, “I just realized I haven’t eaten in many hours, but suddenly, I’m hungry.”

There must be a type of sensation or need to be with nature that I think so many people are not even aware of. But when I give them a little taste of it, this turns on. Other people start to feel the sand at the beach as if it were food and, all of a sudden, it’s like, “Oh, my gosh! There’s so much going on here!” It’s such a rich experience.

Richard: I don’t hear it spoken about per se, how there’s something that can come in directly through the simple sensation of holding sand in my hands, or a rock. It’s something so primal. It actually nourishes something, but you have to slow down enough to let that experience enter.

Zach: Definitely. This nourishing is part of what I tap into in what I’m doing. I’m so lucky, because I’m at the intersection of these needs. There’s the social need to connect with each other; the need to connect with nature—I think E.O. Wilson calls it biophilia—and the need to express and build, to create, the creative instinct. I’m at the intersection of these three things. I literally bring these to people, catalyze the connection, and then it’s like a chain reaction. It happens so beautifully and easily, usually.

I feel so lucky that I’m at this intersection, and I also feel sad that these connections are so lacking. That’s part of why I work with kids so much. With technology being the companion for a kid so much now, they don’t have the companionship of nature, and of each other, and even of adults, really, in the ways they used to. There’s a strong international movement to reconnect people with nature, and children specifically. I’ve worked a lot with groups involved with that.

Richard: You probably know the lack of this connection has even been give a name: nature deficit disorder.

Zach: Right. Richard Louv coined that term. His book, Last Child in the Woods, was a sort of wake-up call to what technology was doing to children, like, it’s “the last child in the woods” because they’ll all be on their machines. Soon after he wrote that book he started the Children & Nature Network; it’s a national group. Early on, I got involved in the local chapter in the Bay Area, The Children in Nature Collaborative. Mary Roscoe lives in the South Bay, and she invited Louv to come and speak. The auditorium was filled with hundreds and hundreds of people.

I’ve worked with the Children in Nature Collaborative and with Mary Roscoe a lot, on different projects. She’s connected me with a lot of different groups to do my work. So, yes, nature deficit disorder is actually a big, big problem.

Richard: I’m so glad we got to this, Zach. We’re all living in our heads, and this whole digital revolution just exaggerates that. We’re so out of touch with nature and our bodies and now we can entertain ourselves effortlessly 24/7 if we want to.

Zach: It’s a huge thing. It reminds me of sad and interesting experiences I’ve had around technology with kids and nature. One young kid, maybe six or seven, was trying to balance one rock on another, and the rock kept falling off. He was putting the rock on top at a diagonal. It was obvious that it would fall off immediately as soon as he took his hand away. I was watching him; my way of working in these situations is not to tell people what to do. Eventually, he turned to me and said, “This would work on my screen at home.” He had such little experience with physical rocks he didn’t realize how one rock balances on another. So that was one scary moment.

Another one was with an older kid, around 12. We were on a field trip at Blake Garden in Kensington. Do you know that place?

Richard: I don’t.

Zach: It’s really wonderful. It’s a UC Berkeley garden, ten acres. They use it as a teaching laboratory for the landscape architecture school, but it’s open every weekday. I have a permanent “Create with Nature” area there also, like I have at Redwood Park. The materials all come from the garden prunings, clippings, fallen trees and such. So it’s really rich.

One day, there’s this kid and his classmates are buzzing around making stuff. They’re making teepees, making crowns out of leaves and just crazy stuff. All of a sudden, this kid sat down on this log, and was just watching all this activity going on around him. Usually, when something stands out like that, I get close to it, maybe he’s depressed, or he feels left out, or maybe he needs some help. So I’m just standing quietly next to him and he looks at me with this look of wonder. He says, “This is so real! It’s almost like a video game!”

I couldn’t believe that.

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola Magazine. A selection of his interviews, The Conversations—Interviews with Sixteen Contemporary Artists, is available from the University of Nebraska Press. This interview was first published in works & conversations #35 July 2018, and edited for this publication.

www.conversations.org

Zach Pine’s website: www.zpcreatewithnature.com

@sandglobes

@beachpropellers

All imagery is used with permission and is copyright of Zach Pine unless otherwise stated.