Composer, music educator, and concert pianist Paul Davies recently completed his first full length opera based on the life of Charlotte of Belgium who was Empress Carlota of Mexico during the period in Mexican history known as the French Intervention.

Davies received a Ph.D in music from the University of California at San Diego. He currently teaches composition, music appreciation, music theory, and a course on the Beatles at Foothill College in Los Altos Hills, California. Davies has also appeared as soloist with the Foothill Wind Ensemble, the Winchester Orchestra, and the South Valley Symphony.

Whirligig: You recently completed the writing of an opera, Carlota. What inspired you to write an opera?

Paul: I had been invited to give a talk about my music and present a new composition, an instrumental ensemble piece, at the Ernest Bloch New Music Festival in Newport, Oregon, in July of 1999. I was at one of the festival concerts where another composer premiered a new chamber opera of his when the idea of doing an opera myself flew into my head. I had been thinking of the tragedy of Empress Carlota for quite a few years before this, but never with the idea of doing an opera on the subject.

I suppose another impetus was that I’ve always been fascinated by history and of the possibility of traveling back in time. So doing an opera on Carlota is the closest I’ll ever get to time-travel, so to speak. I realized that my research would involve reading every major book on the subject I could get my hands on and also traveling to Mexico City to visit Chapultepec Castle, where Carlota and the Emperor Maximilian lived during their short reign. I very much looked forward to this.

Whirligig: What path did your research for this project take you on?

Paul: Since I was intent on doing the text myself, I spent a lot of time researching how to do a good libretto, and I also consulted with two dramaturges who gave me much invaluable advice. I analyzed quite a few librettos to gain further insight. Also, I came across very interesting photographs of the time period. I remember being at the library of San Diego State University and finding a photograph of the moment Maximilian and Carlota enter Mexico City in June of 1864.

Every time I read about an historical event, there’s always at the back of my mind this very small sense of myth, a sense of maybe what I’m reading about didn’t happen since I wasn’t there to actually see it. It’s not that I don’t believe the event happened, or that the historical figure in question never existed, It’s just that tiny feeling of “unreality” since I didn’t experience it myself. But when I saw this photograph I almost jumped and said to myself, “Wow, this really did happen.” I get the same kind of feeling when I look at a life mask of Beethoven, or some other figure for whom the only visual representations are idealized paintings. If I hadn’t been a composer, I probably would have been an historian.

Whirligig: What were the most surprising things that you encountered or uncovered?

Paul: In 2004, Nieuwe Ensemble, Amsterdam, performed a piece of mine for solo guitar and ensemble, Genji’s Visit to Utsusemi. They had given the premier of this work some eight years before. I decided to go to the concert as it would give me a chance to later travel from Amsterdam to Brussels. Carlota, or Charlotte, as she’s known in Belgium, had died in 1927 at the Castle of Bouchout, on the outskirts of Brussels, and I wanted to visit this place. I called ahead and was told that Bouchout Castle is now a convention center and that there would be little of historical significance inside, but that I was welcome to come nevertheless. While in Brussels, I was also surprised to find that in the museums I visited there was hardly anything at all on Charlotte. In Belgian history she’s not much more than a footnote, she was actually the sister of the infamous King Leopold II, but in Mexico any little kid on the streets will know who you’re talking about if you say the name Carlota

Whirligig: What elements did you invent? What parts are fact and fiction?

Paul: In one of the books I read on Carlota I came across a quote from Jorge Luis Borges, “History has its own poetry.” I very much believe that to be true. It’s always disappointing to me to watch a movie on a historical subject and find that many things have been distorted or outright invented to make the movie more dramatic. The 1994 movie, Immortal Beloved, about the mysterious woman with whom Beethoven was in love and whose identity has never been satisfactorily established, is a case in point. Hollywood invents a number of situations that lead us to conclude that it was Beethoven’s sister-in-law who was the real Immortal Beloved, which any serious writer on the subject will tell you is an absolute impossibility.

I very much wanted my opera to follow the facts as they happened because I think they are dramatic in themselves, but I was surprised to discover that one does, in fact, have to change one or two things to make the story live on stage. It’s one thing to read a book on history in the comfort of one’s bed at night, but quite another when you have to make something work theatrically. So while a good eighty percent of my opera is based on fact, I did invent two or three situations.

The ending of Act I, for example, involves Maximilian and Carlota making a triumphant entry into Mexico City. I invented a scene where, as Maximilian is about to be crowned Emperor everything freezes and only Carlota can move. She takes the crown from the Archbishop of Mexico and puts it on her husband’s head. She then sits on the imperial throne. Another example is when Carlota goes back to France to confront Napoleon III and persuade him to not withdraw his troops from Mexico. In reality, this meeting took place in a small room at the Tuileries Palace in Paris between Carlota, Napoleon III, and his wife, the Empress Eugenie. This part of the story is crucial since we know that it was here that Carlota began to go mad. I decided that to follow history exactly would not be too interesting on stage, so I created a scene where Carlota barges in on a masked party given by Napoleon III at the palace. This scene opens the final act of the opera and I think works far better dramatically since her frustration at getting nowhere with the Emperor of the French escalates to the point of her going insane in front of the crowd of guests attending the party.

Whirligig: Are the story lines of most operas this dramatic?

Paul: Many are, and I’ve read storylines that on paper don’t seem that dramatic, but then you hear the music that goes with them and they’re incredibly so. Of course, it all depends on how well the composer has matched an especially dramatic scene with the appropriate dramatic music. The end of Verdi’s Aida is a case in point. Radames is condemned to be buried alive in a tomb. He realizes that Aida, the woman he loves, has managed to get into the tomb to die with him. The words to the last aria they sing together are not particularly dramatic, but Verdi composes a hauntingly beautiful melody for these words that matches the poignancy of the moment and raises those words to almost great poetry. Not only that, but Verdi also paints in a high string chord that rises and falls in volume, symbolizing the idea that the lovers are gradually losing oxygen as they die together.

Opera has many examples like this. But drama can be tricky. Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress is about a man who sells his soul to the devil for the usual material wealth, power, etc. When it’s time for Tom to give up his soul, he’s able to trick the devil by winning a card came, whereby he saves his soul but loses his sanity. This ending has been criticized as not being entirely believable since everything that’s happened in the opera prior to this has lead the audience to expect the worse, that Tom will, in fact, lose his soul.

Whirligig: Writing an opera is clearly a balancing act involving music, story and text, staging and performance. Talk to us about your process. What is involved?

Paul: Yes, it is very much a balancing act. You would think that the process would be to first write the libretto, then go back and set it to music scene by scene. But years before I even began to write the libretto I found myself composing snatches of music that would fit certain scenes that I envisioned. I wasn’t even trying to finish these little bits and pieces of music but merely attempting to create certain auras or overall moods that would fit a given dramatic situation. It’s something like going to a party and just standing still for a bit with a drink in your hand trying to get the feel of the place, so to speak. Then when I went on sabbatical last year, it was a matter of making myself get up at 5 or 6 in the morning and start chiseling away. The libretto was done in four months, between late August and early December of 2011. I began the music in January 2012, and finished it July 16th. Possibly the hardest part of the process involved keeping in mind what the total duration was going to be: I set myself a duration of no more than two and a half hours. But keeping to this was not easy and I did have to cut things out of my libretto and music. The staging and performance part I haven’t even arrived at yet since I now have to do a piano/vocal reduction of the whole score because this is what is used for rehearsals and for blocking out scenes.

Whirligig: What is a piano/vocal reduction?

Paul: Once an orchestral score is done, opera directors want to look at a piano/vocal reduction of the score. It means that the composer needs to transcribe for piano everything he or she has done for orchestral instruments. This way, only one pianist is needed for the rehearsals, which saves time and money. So the piano/vocal reduction looks like a score with the singers accompanied by a piano.

Once the basic rehearsals and blocking out of scenes has been done, then a few rehearsals would be done with the full orchestra. My opera uses a chamber ensemble of ten instruments: flute, clarinet, harp, piano, two percussionists, two violins, one viola, and one cello. The music that I’ve written for this ensemble now needs to be transcribed for piano. It isn’t always possible to get every single note one has written for the ensemble transcribed to piano, but one tries to get the essential parts down.

Whirligig: Now that Carlota is completed, what is the process for having it performed?

Paul: Besides the piano/vocal reduction I mentioned earlier, one contacts opera companies. I made a few connections over last summer, one of them being the Hidden Valley Seminars held every year in Carmel Valley. I attended a performance of La Bohéme and met the director and stage designer who seem very interested in looking at the score. I’ve also been in contact with Bellas Artes in Mexico City in the hope of doing the opera there.

Whirligig: Opera has a long history and is respected as a high art form. What is the role of opera in our contemporary times? How has it changed for today’s audience?

Paul: During the time of Bach opera was kind of like what the big blockbuster movie is today —it was a big event and you just had to go see it. By the 19th century opera had reached a golden age where some composers refused to look at opera as mere entertainment but started injecting philosophical and even religious ideas into their work. Many operas today continue this line. And even though since 1915 opera has had to face hard competition from the Broadway Musical, it still, I think, reigns supreme when dealing with tragedy. Musicals that have sad endings are few and far between and I have the sense—great musicals like West Side Story notwithstanding—that the genre is not altogether comfortable with tragedy, maybe because the form itself is more closely tied with having to be entertainment than opera is. We tend to forget that the Broadway Musical was a direct descendant of late 19th century operetta, or comic opera. So it seems to me that audiences find opera much more satisfying when it comes to getting across a great tragedy through words and music.

Whirligig: Is the language of operas historically Italian?

Paul: Well, it was the Italians who invented opera, so initially and for a very long time, Italian was the language most composers used. There were exceptions, such as Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, considered the first great opera in English. There’s a famous scene in the movie Amadeus where Emperor Joseph II wants to commission an opera from Mozart and he suggests a libretto in German, but his advisors, who are Italian, tell him that German is, “too brutal for singing.”

When I started to do my libretto, it was suggested I do it in Spanish. Even though I lived many years in Mexico and am completely fluent in Spanish, I opted for English, my native tongue, since I had more faith in my poetic ability in this language. Yet, somehow, the romance languages often seem to fit operatic singing better than English, at least to my ears. English is great for rock and roll, but for opera I don’t think it always works as well. I’m not really sure why this is.

Whirligig: What is the language of Carlota?

Paul: Her native tongue was French, but both she and Maximilian actually spoke six languages. They began learning Spanish as soon as they accepted being Emperor and Empress of Mexico. Carlota spoke it perfectly, with almost no French accent at all.

Whirligig: What made you want to be a composer?

Paul: More than anything it probably was the fact that in my teens I was continually doing something in music. I spent long hours each day just picking out the harmonies from songs I’d hear on the radio. I later taught myself to play drums just by using my bed, pretending that pillows were cymbals and using a piece of large cardboard under my feet to get the hollow sound of the bass drum. I bought a guitar and the guys in the rock band I had joined taught me chords, which enabled me to start composing my own songs. This all happened between the ages of 14 and 17, and at the end of that time I decided that that’s what I wanted to do in life, compose.

Whirligig: Other than teaching a course on the Beatles, do you continue to play and appreciate rock or other mainstream music genres?

Paul: I listen to rock and roll once in a while, but I have to confess that the contemporary music scene doesn’t speak to me as it once did. It’s interesting that every quarter the majority of my students in my Beatles class complain about the current pop music scene in that much of it seems to be based on the image the performer projects rather than on any artistic merit in the music. But at the same time, I’m keenly aware that one can easily fall into that old mistake of saying, “Why don’t they make music like they used to?”

There’s an interesting story about Andrés Segovia, who more than anyone raised the status of the classical guitar to where it is today. Soon after Beatlemania broke loose in England, George Harrison was asked by a reporter what he thought about Segovia. Harrison answered, “He’s great. He’s the granddaddy of us all.” Harrison implied that Segovia was, as a guitarist, a kind of father figure to guitarists all over the world. George’s comment got back to Segovia, who reportedly said, “Those kids are not even my bastard children.” Segovia was appalled at the whole idea of the electric guitar; he thought it was a perversion of the instrument. But what impresses me is Segovia’s inability to see the beauty of the Beatles’music, or of the electric guitar, for that matter. This kind of thing happens over and over again. Debussy was very fond of Stravinsky’s music, but once Stravinsky premiered The Rite of Spring, in a letter to a friend Debussy expressed concern over Stravinsky’s new piece saying he thought Stravinsky was going the way of Schoenberg, a composer who Debussy disliked. In his last years, Bach completely ignored the new developments that were taking place in music during the 1740s and went on composing his marvelous fugues, which for the younger generation had by that time become irrelevant. So I’ve come to the conclusion that, if it’s important enough, one should make an effort to understand why something that is artistically new is so different from what one is used to, and not immediately discard it as not music.

This issue also leads me to wonder, if he had lived, what Bach would have thought of Beethoven’s mature style, what Beethoven would have thought of Wagner, what John Lennon might have thought of Lady Gaga. Impossible to know, I suppose, but fun to think about.

Whirligig: What are the highlights and the low points of the creative process for you?

Paul: Well, there are three low points for me, which I imagine are true for almost any artist. One is staring at a blank piece of paper and not having a clue as to how to begin. The process of doing Carlota frequently reminded me of looking at a huge mountain and not seeing any way to climb it. Yet somehow a way always presents itself.

A second low point is doing a piece of music that you thought was very good, then you discover after the performance that it doesn’t work. This happened to me in 2001 with a piano quintet I wrote. After listening to the recorded performance a number of times, I realized that only the ending worked, the rest had to go into the garbage can. But the nice thing is that one can always recycle things, and I used that ending for Carlota’s final aria in my opera. The third low point is in some ways the opposite of the second. You write a piece that you know is good but then receives a terrible performance, or maybe it was well performed but you, the composer, were the only one who liked it. A kind of sick joke played on you by the gods, you might say.

One highlight for me has to be when a piece starts to live, when you know it’s working and you feel that nothing is going to screw it up. And then there’s the feeling of just working, work for its own sake. The creative process is, to me, a sophisticated form of meditation. Then it’s almost like being high, where you’re so caught up in the piece that you don’t even want to go out for groceries. I’ve had this experience a few times, but it’s rare.

Whirligig: Do you have an ideal working environment?

Paul: The best place is my own study where I can set my own schedule and not have to worry about anything else other than the work at hand. I read somewhere that Brahms’ schedule was to always get up at 5 am, compose until noon, then go to his favorite restaurant and have a big chunk of pork with sauerkraut and a stein of good German beer. I’ve always been attracted to this idea of working on a schedule, like punching in a time card everyday. Many artists work only when they feel inspired. For me that’s never successful.

Whirligig: What aspects of culture are poignant and important to you as a cultural consumer?

Paul: Anything that is informed with a sense of the past. I feel that we live in a society today that pays far too much attention to youth culture where often the past is considered irrelevant. There’s this constant push to upgrade, to be “on the cutting edge” which has resulted in a feeling that what is new is the only thing that is valuable. But I’m a little tired of going into a Starbuck’s and watching four people at a table not one of which is talking to the other because they all have their heads buried in their iphones. It’s also sad to see that fancy technology will often be passed off as art. I once went to a concert at Stanford where the newest electronic equipment allowed the performer to simply wave a wand and make sounds. As a demonstration of new technology it was fine, but the whole thing was presented as a musical concert of artistic pieces of music, which it definitely was not.

Whirligig: Tell us about works that have been transformative for you.

Paul: My favorite all-time piece of music is Gyorgy Ligeti’s Lontano for orchestra, composed in 1967. I remember very clearly when I first heard the piece that I neither liked nor disliked it, but something in it kept me going back to listen to it again. It taught me some things. Great art can sometimes have this quality of quietly attracting you to it, like the sirens in Homer’s Odyssey. It also pointed the way for me in my liking for abstract visual art.

Luciano Berio’s Sequenza VII, composed for solo oboe, was also transformative. This work is completely informed by the past but it places it in a new context. The best work of the major composers from the post-war era has this quality.

Whirligig: What is your next project?

Paul: A friend of mine suggested I do an opera on Mary, Queen of Scots. It’s a subject not unlike Carlota in that both woman were called to rule a country they were not familiar with and both had tragic ends. For that reason, I’m not sure it’s the thing I should do since there’s the danger of repeating myself. So for now, getting that piano/vocal reduction of Carlota will take most of my time for the next six months or so.

Paul Davies website: www.daviespaul.com

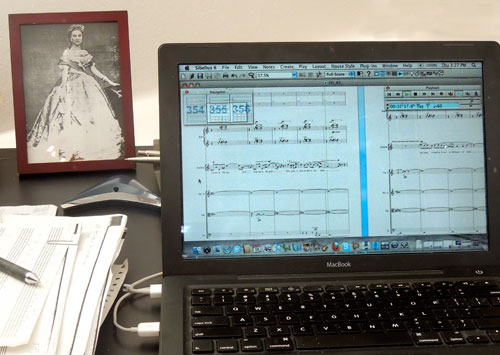

Images from the top: Paul Davies at the piano, Paul’s desktop workspace, a page from the score of Carlota. Photographs by Kent Manske.