Ever Rodriguez was born and raised in Mexico and has lived in California since the early 1990s. He writes prose and poetry on themes related to his experience, including immigration, biculturalism, music, language and nature. Ever is a pragmatic writer for whom the common becomes the special as a way to contrast the abject against the normal. His education includes a B.A. in Spanish Literature and a M.A. in Library & Information Science from San José State University. He has worked for the Stanford University Libraries for the past 25 years. Ever’s letterpress studio, La Feroz Press, focuses on handmade editions with original texts and translations. His work often has the intention of amplifying the voices and concerns of his marginalized community.

Although we live a short bike ride apart, we conducted this interview via email while sheltering-in-place during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Whirligig: What is the history of La Feroz Press?

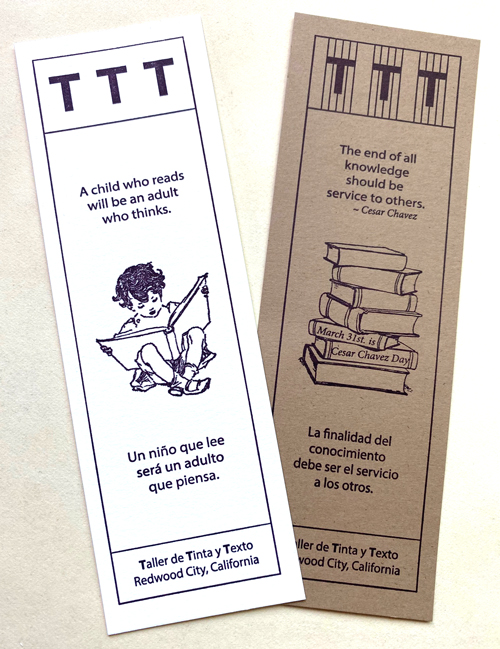

Ever: La Feroz Press officially started with this name in January of 2019. We had been working under the name of Taller de Tinta y Texto since 2015, which was the time when our printing press project really took shape. It is wise to say here that when one has the intuition or the wish to do something, one has to follow up with at least one decisive action that would move further towards that direction to really get started.

For me, the decisive action that put me on the printing track was taking a letterpress class. This allowed me not only to learn the basics of letterpress printing, but it also laid out the challenges I would need to overcome in terms of space and equipment, and it put me in touch with the printer and bookmaking culture and communities that would inspire me to fully embrace this activity.

Out of such initial inspiration I was able to create a space for myself at home where I could potentially house a printing press and other essential equipment. For years our one-car garage was filled with unused furniture, souvenirs and unwanted items, so one day I just decided to get rid of all of it and remodel the space to make room for a printing studio.

Once I had the space, I started itching to find me a press. At first, I was looking for a hand press, but those are as rare as they are expensive, and I even started looking at the possibilities of making my own wooden hand press. I figured that if Gutenberg’s contemporaries were able to build those presses without the tools we have today, I should be able to build one press half as good. I found and bought a book entitled The Common Press, by Harris and Sisson, which has drawing plans and notes about the construction of the Franklin hand press, owned by the Smithsonian Institution. But I deviated from that adventure for a different alternative.

In January of 2015, I found a small press for sale online. The press was not ideal, and it was certainly nowhere near the Franklin hand press, but it was an inexpensive alternative that would get me started. So I bought it and the next day I drove to Los Angeles to pick up a midsize (14 x 24) Morgan Line-O-Scribe proofing press. This was the very first piece of equipment that I owned, and it came with a little bit of awful metal and wood type, but that satisfied the itching.

I experimented with that proofing press for about one year, and then Matt Kelsey—printer and owner of Camino Press, in Saratoga, California—told me about a Chandler & Price (C&P) 10×15 platen press that somebody was selling in Gilroy. I decided to buy that press, and a few printer friends helped me pick it up, bring it to my garage and install it. Mark Knudsen and Kim Hamilton made beautiful wooden feed boards and a treadle for it, and other printer friends gave me some tools and made me feel welcome to letterpress printing.

The acquisition of this C&P press gave me added impetus to get more serious about letterpress. I acquired both new and used metal type and other essential tools and items through friends and referrals, and then I started to get more adventurous with printing and designing other things beyond postcards. All along, my wife—who I call Gaby—had been supportive about my new adventure, and I think that when she saw me purchasing that big, old C&P press and hauling it into our garage, she realized that my temporary craziness had turned into long-term seriousness. I think she was happy but surprised and concerned all at once. Once Gaby realized that these old devices and tools were here to stay, and she saw how excited I was about them, she got excited as well and started making lemonade with my lemons.

A couple of years passed, and in 2017 our friends Linda Stinchfield and Kim Hamilton gave us a beautiful Griffin etching press, thus helping me to expand my horizons to allow for more and better relief printing, which now includes linocuts and occasional woodcuts. Finally in June of 2019, I was lucky to bid on and win a Vandercook SP15 press at a local auction and that is now part of La Feroz Press.

By then I had taken several letterpress printing classes and I even earned core letterpress diplomas from the San Francisco Center for the Book on both the platen and the cylinder press. So far that is the story of La Feroz Press, which is still in the making.

Whirligig: La Feroz recently experienced a name change. What was behind this?

Ever: In the beginning I was excited with the name of Taller de Tinta y Texto, which alluded to the passionate union of personified Ms. Ink and Mr. Text—in genderized Spanish these would be La Tinta and El Texto—which, when put together on the bed of a press, they would engender texts as a result of their fiery encounters. All puns were intended. This name was conceived by the assumption that, for the most part, I would be printing poetry. But as time went by, I realized that many other aspects from our lives were percolating, particularly as we dealt with some community issues (Gaby is a Nurse Practitioner at a local clinic). You know how sometimes you plan something and that something ends up planning you differently? That happened to our printing press, so after some time we felt compelled to change the name to make it more inclusive and reflect the place where we were working: the unincorporated and marginalized community of North Fair Oaks which is adjacent to Redwood City, Atherton and Menlo Park.

The name La Feroz actually arose from the Latinized pronunciation by some immigrants and fellow residents who were referring to our barrio of Fair Oaks pronouncing it Fer-Oz, which coincides phonetically with the Spanish word Feroz, meaning ferocious. In our minds that pronunciation alluded to a barrio bravo, a brave and resilient neighborhood, which is what North Fair Oaks is, as well as to the mythical jaguar venerated by Mesoamerican cultures. At the same time, the name La Feroz alluded to the multiple meanings that our press aspires to embody through the production of relief and letterpress printed works: organic, fierce, and with an occasional bicultural bite. La Feroz turned out to be the perfect name as it is an expression that reflects the language, the culture, and the geographic (dis)location of the people who happen to be an essential piece of this big and diverse social puzzle.

Whirligig: Describe La Feroz’ aesthetic.

Ever: Being a writer, I believe in the power of text to convey a sentiment, to tease imagination, or to pique the interest of whoever reads or sees the text. Therefore the aesthetics of La Feroz Press, although still important, take a secondary place to text or meaning. Letterpress printing has indelible marks that provide visual and tactile qualities, and the inclusion of relief printing is diversifying my views and providing alternative ways to communicate beauty. Gaby’s aesthetic eye often influences the outcome. But in general, I think we can loosely and happily remain within the realm of the naive as neither one of us has formal art training and we only go by our artistic intuition.

Primarily we are our own audience and thus produce the things that we like to see. I have a particular quirkiness that at times is natural and other times intentional, often as a way to mock, confuse or even as an attempt to criticize or correct the division that exists between what is considered art and craft. I think this comes from the deep respect and admiration that I have for human craftsmanship and self-didactics.

One time, while visiting a Mexican indigenous community in the mountains of San Luis Potosi with Gaby and my musician friend Artemio Posadas, I saw a group of local musicians. The fiddle player, who was an older man, had carved his own violin out of a log and had also made his own strings to be able to play his music. He was playing with pride and happiness and he/they had an audience captivated and happy as well. The fiddle was roughly cut and it didn’t even have varnish, sanding or polishing, but it was beautiful in its roughness and most importantly, it produced music. I thought, if that whole expression isn’t art, then what is?

La Feroz Press is not intently looking for an aesthetic that is recognizable or that defines or distinguishes it in some way, but just like the renaming of our press came about very organically, maybe an aesthetic will develop over the years to distinguish our work. Only time will tell, for now we are open to experimentation without worrying about it.

Whirligig: How did you come to letterpress?

Ever: Late in 2011, I had casually met Mike Day—owner of Long Day Press (Sunnyvale) and long time letterpress master printer teaching at Foothill College’s Studio 1801. I had met him during his visit to Stanford University’s Special Collections, where I still work today. I found out that he was teaching a letterpress class. A couple of months later, in early 2012, Gaby pursued the idea and insisted that I take that letterpress class. It is fair to say that Gaby’s encouragement was the catalyst for what was the beginning of my romance with letterpress printing and the graphic arts.

I took Mike Day’s letterpress class again the following year, not only to learn more printing tricks from him but also to have access to the printing equipment, which is difficult to find and acquire. While taking those letterpress printing classes I also met other graphic artists and letterpress enthusiasts, including Linda Stinchfield, owner of Turtlesilk Press, and Kim Hamilton, owner of Two Left Hands Press (both of Los Gatos).

After having made a solid friendship with Mike Day at Foothill College, he invited me to be his guest and attend his printing club’s meeting, where I met the members of the Moxon Chappel in December of 2014 at the headquarters of the Elmood Press (Campbell). This meeting resulted in a collaboration with Mark Knudsen, printer and owner of Elmwood Press, who printed beautiful bilingual versions of some of my poems. And it also resulted in subsequent invitations to Moxon Chappel meetings, thus favoring my possibilities of becoming a member of the group, which has been meeting for nearly 65 years, and whose archives are held at various academic settings that include Stanford University, UC Berkeley, UCLA, the Huntington Library, the California Historical Association, the San Francisco Public Library, and Santa Barbara Public Library.

But way before I took that first letterpress class at Foothill College, I had been writing poems and short stories, birthing them as if they were my children, and saving them without making any concerted efforts to publish them. That was because early on I had been disenchanted by the publishing industry and I knew that, first, I didn’t want my next meal to depend on my writing; and second, that I was not willing to let something as personal as my writing be [mis]handled by a business-making enterprise.

When I learned what I could do with letterpress, a fire ignited and I knew that this would be the perfect conduit to let my children go out safely and meet the public. That is how I came to letterpress.

Whirligig: Tell us about your collaborative process?

Ever: Our collaborations are as random as they are organic. When I come up with a design for a card, a broadside, a poster, a book, or any other print, Gaby comes in, sees what I am doing and suggests things I could do or things that she can do to help me finalize it. Often she offers help with bindings, and sometimes I recruit her help on any aspects were we can converge knowing that her main hobby is sewing.

I have several examples where it is obvious how my printing work has been complemented by Gaby’s intervention. For example, I printed one of Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets to send it to the Bodleian Library in Oxford in 2016 when they were commemorating 400 years since the Bard’s death. This print would not have been as impressive without the sewn envelope that she made for it.

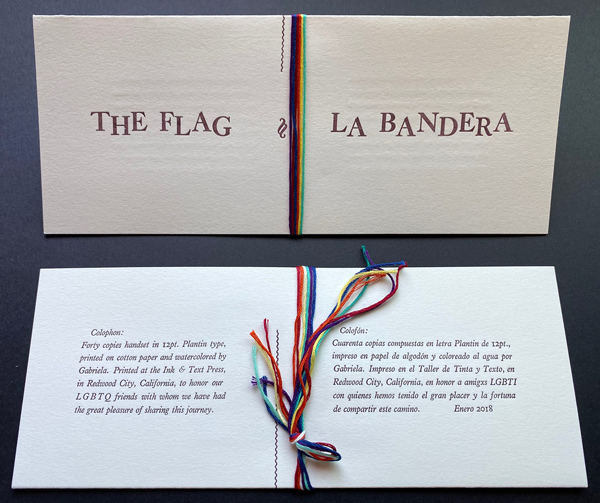

I also printed a card highlighting the pride rainbow flag to honor some of our friends; and instead of using a regular envelope for the presentation, Gaby assembled several colored strings of thread and then tied them in a knot around the card. This gave the print a really nice aesthetic push and added meaning to the message printed on the card. It underlined the meaning of inclusiveness that the rainbow flag has with its colorful design and its allusion to the many, rather than the few. With this project we wanted to highlight that view and also to honor those who have been ostracized, disrespected and abused for being who they are.

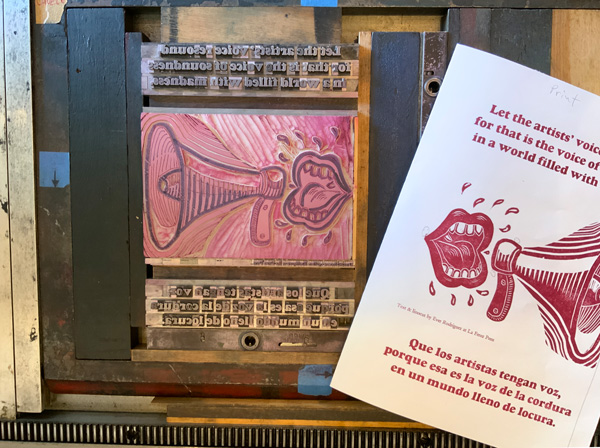

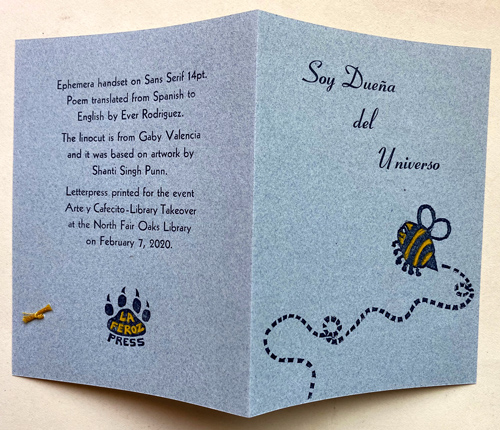

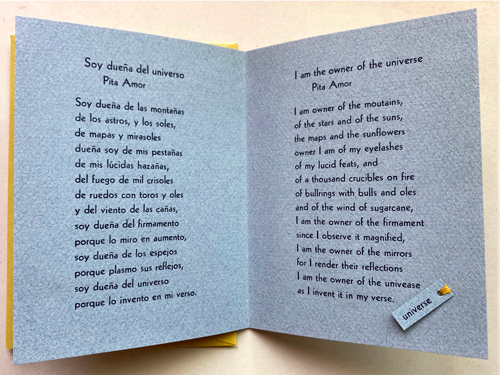

One project that I love as an example of our collaboration is a poem from the Mexican poetess Pita Amor that I printed for Gaby. We included a linocut carved from an image that the daughter of Gaby’s boss had drawn and given to her as a card. Everything turned out very nice; however, once all the cards were printed, we discovered an evil typo that had somehow escaped our proofreading and slipped in the final printing. In the case of a book, one can print an additional page and include it as an erratum; but in a small card with one single poem, one either has to reprint the entire run or be very creative. We chose the latter and decided to print the individual misspelled word, cut it to size and sew it onto the card, right next to its corresponding misspelled word. Again, this added another dimension as a visual element and as a recognition that life is not perfect even when we aspire to it.

I am thankful that Gaby chose sewing as a hobby and not welding, but I am certain that even with welding, I might be able to recruit her help to finish something with that type of skill. She also helps me to read and edit some of the texts I write, often prompting me to reconsider textual content as well as project design. For all of it, I am thankful to her and very happy with our collaborations.

Whirligig: How do you come up with concepts and their execution?

Ever: Many of our projects come straight from my writing, just as those poems or short stories become relevant or claim to meet the public eye. Other projects are influenced by our surroundings, particularly as they relate to the people that we cross paths with.

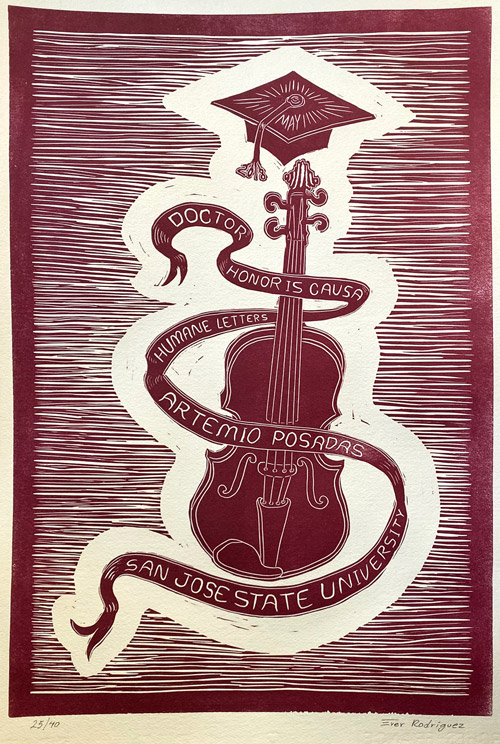

The very first poster I printed was for my musician friend, Artemio Posadas, who received the National Endowment for the Arts’ Heritage Fellowship medal back in 2016. The accomplishment was such a major event for the Latino community that I felt I could not possibly stay stagnant. The poster had several challenges as I wanted it to emulate the body of a Mexican jarana (a smaller-than-a-guitar stringed instrument) and in it include the shape of the actual medal. It was my first time combining letterpress and relief printing on my small, clunky proofing press. Two years later I did a poster on relief printing for the same friend, this time as he was receiving an Honorary Doctoral Degree from San José State University. Both projects were a true labor of love.

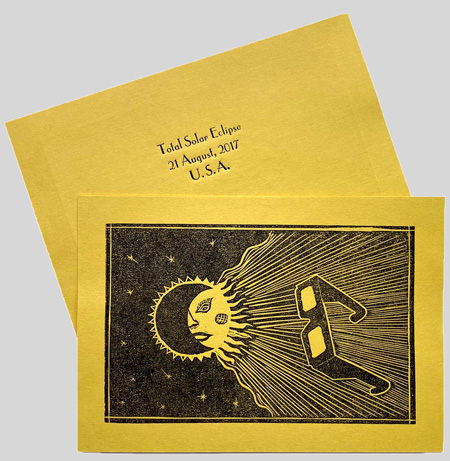

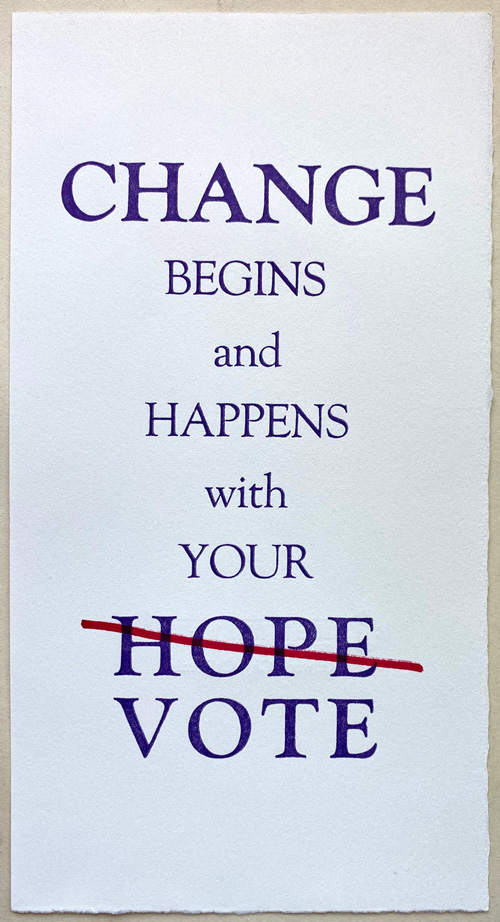

Socio-cultural happenings also spur my creativity, like the card I printed during the total solar eclipse that took place in 2017, where droves of people were getting excited and driving to the state of Oregon from many places just to be able to see such a natural phenomenon. Sometimes I also print ephemera related to national or international affairs, such as the recent death of my hero John Lewis, for whom I am printing a poster that includes some of his most memorable quotes. The rainbow flag card project that I mentioned before is a good example of how my art practice is informed by what our society may be going through. I am not patriotic in the very least, so for me to print anything around a flag needs to have an added element to be worth the trouble. In the case of this rainbow flag, I have always thought that, if a flag is to be representative, it first and foremost needs to be inclusive.

I have also printed ephemera with original poems to celebrate friends, like the 70th birthday of my friend Juan Pascoe, owner of the legendary Taller Martin Pescador in Mexico, and whose work has uncovered so much history about the development of the printing press in Mexico—the first place in the entire American continent to have a printing press in 1539. I also print celebratory ephemera, like the card I printed to honor Fred and Barbara Voltmer, our friends and Moxon Chappel companions, who received the Oscar Lewis Award for the Book Arts from the Book Club of California in April, 2019.

Finally, I have already mentioned that I am a member of the printers’ group called the Moxon Chappel. By joining this group one commits to printing at least one piece of ephemera and shares copies with all members at each monthly meeting. At these meetings we look at each other’s prints and give feedback or kudos on the merits of the printed projects, often suggesting alternative techniques, tools that would help the work or advice on how to improve such projects. These meetings are one more incentive to print something at least once per month.

From there on, I print more mundane items, like stationary for ourselves and as gifts for friends, and letterpress printed bookmarks to include with some of the books we give away through the Tiny Free Library we have right outside our house, etc.

Whirligig: You also publish translations. Tell us about the translation process, and how/why you select certain authors/works.

Ever: Where I can, I try to include both English and Spanish versions of the texts I print or publish. It feels right and it feels essential for me—a bicultural and multilingual individual—to include as many linguistic or cultural entry points as I can to allow the different cultures I move through to intercommunicate and to understand each other. Translating creative texts in particular can be a pain in the brain; but at the same time, the chance of enticing someone to look at “the other” through the lens of art (as poetry or prose in translation does) is a thrill that keeps bringing me back to do double the amount of work: translating, composing type, and then printing both versions.

Ultimately, I think that the thrill I get with translations responds directly to my desire to share the wisdom that certain texts and authors have. I think that some people like me, whose life experience as immigrants force them to live an existential duality, at some point discover that both cultures have huge merits and wisdom that could be useful or even life changing if it can only be learned and shared. That is why some of us become bridges that attempt to communicate two opposite or distant sides, to offer a viable and safe path for strangers to travel. These days, when diversity abounds even to the point of becoming a cliché, I know for a fact that two cultures are better than one.

Let me give you one example. Last year I collaborated with Derli Romero, a visual artist from Morelia, Mexico, who makes artist’s books. For his latest project he went to many locations where immigrants coming from Central America and Mexico seeking to migrate to the USA stop. He spoke and made sketches from them. Then he asked me to collaborate with him by writing an essay based on his sketches. I said yes, and to me it was a given that we would make a bilingual Spanish-English edition, but when I told him he seemed surprised and asked me why we needed the English version. I told him that, given that this was a topic that affected many people of both sides of the border, it would be great to have that language link to promote better understanding. The suggestion grew on him and later he told me that he loved the idea, so the portfolio was made bilingual.

There are other aspects that are advantageous to making bilingual editions. Of course one is the language/culture extension it creates, but this alternative also helps to promote ideas, art and artists in cultures that may otherwise never hear about such works or artists. But I feel like, particularly for countries in the American continent, it is very important to create those language/culture linkages as much as possible given that our lives are tightly interrelated.

I translate both, from Spanish to English and from English to Spanish, and neither one has become easier. Both make me consult dictionaries often, and finding the right terminology that conveys both the concept and the sentiment is always a challenge. I think that is where the automated, artificial intelligence translators fail, in conveying the sentiment of a statement, and I am glad to see that there is still a future for humans in that regard.

Currently, I am working on two separate booklets that contain one original poem each and require Spanish to English translations. One is from a poet who lives in Barcelona, Spain and the other is from a poet who lives in Morelia, Mexico. Both texts represented a challenge during the translation, but I was very happy with the results and so were the authors. Each poem has its own challenges in terms of length and possibilities for presentation, as in letterpress often the length of your type determines the space and the boundaries you can work with. In this case both poems will include illustrations; one has a single photograph, and the other has two linocuts done by another Mexican graphic artist. I have three similar projects of my own waiting in the back burner.

Whirligig: Your studio is exceptionally lovely and well maintained. Do you have any favorite stories about your equipment?

Ever: Thank you. I wish I had more time to spend in the studio to get better organized and maximize the space given that it is only a one-car garage and every inch counts in there. At the same time, the reduced size of the studio makes it feel a little cozy, so much so that the Shakespeare quote, “I like this place and could willingly waste my time in it.” resonates with me. Even when I am not printing, just being in there relaxes me and it often spurs my creativity. This speaks volumes about having a dedicated space for art making, regardless of the size, and particularly as the Covid-19 pandemic has forced most of us to shelter-in-place.

In terms of favorite stories about my equipment, and given that most letterpress equipment is no longer being made—particularly printing presses—it is always interesting to meet the folks who sell those items and to know their histories. For example, the first proofing press I acquired in L.A., its previous owner was an art teacher. I know this press came from a place of joy because that teacher told me that she and her students, and even her teenage daughter, had printed artsy stuff on it and they had gotten a lot of fun and joy from it.

Not all presses come from happy endings though. For example, the platen press I acquired in Gilroy had been sitting unused for more than 15 years in the woodworking shop of a guy who had always wanted to do letterpress printing but who, for one reason or another, was never able to carry out his dream or passion. He sold the press to me for $50 because he said he wanted it to go to somebody who seemed genuinely excited about it as he once was. This platen press we ended up naming it the Frankenpress (alluding to Mary Shelley’s monster, Frankenstein) because of its awful looks when we first saw it as it was covered with cobwebs and it had thick layers of sawdust glued over dried grease. But the name was also fitting because we found it right around Halloween. It took me several weeks to thoroughly clean and adjust it, but I was happy once I finished bringing this monster back to life.

After the Frankenpress, I made it a tradition to name our printing presses. The beautiful Griffin etching press that we received from our friends Linda Stinchfield and Kim Hamilton I simply named it Linda, which in Spanish means beautiful or being very nice. This name is alluding not only to the nice gesture from our friends, but it also honors two other close friends that we have with the same name. Finally, the Vandercook SP15 came from an even gloomier story as it was auctioned off with an entire printing shop after the death of the previous owner, who I never met. I named this press Espy, which is the short Spanish for Esperanza and translated to English it means hope. But the name Espy also has similar phonetics as the English spelled abbreviation of SP (Standard Precision), which is the model series for this press.

But in letterpress you never know when some equipment is going to come begging you to take it. For example, the times that I had been looking for a Vandercook press, I was never able to find a suitable purchase. And one day, it just showed up and bam! I had it. The same thing has happened to me with a few type cabinets, a book press and other tools, which all of a sudden I received and, not having the space for those, I ended up donating them to Paula Sheil, the founder of the Tuleburg Press, which is a really cool community printing studio in Stockton, California.

It is sad to say, but in this occupation sometimes it only takes a fellow printer retiring from the activity or dying for all his or her equipment to start desperately looking for a new home. It is extremely sad when the equipment ends up going to the scrap metal yard or worst, the landfill. But the best is when another passionate printer benefits from that equipment and puts it to good use.

Whirligig: Are you a letterpress purist, always handsetting your type and hand cutting your illustrations, or do you engage in digital tools such as photopolymer plates?

Ever: I try and always prefer handsetting metal or wood type and making my own illustrations when possible; however, sometimes my limitations can force me to use other technologies, including photopolymer plates. Considering that type is expensive, I have only a handful of fonts in certain sizes to try to cover my bases, but projects can have varying challenges and demands, and that is when I have to scramble to find a good alternative. Plus having metal or wood type also demands space, and as I have already mentioned, my space is very limited and limiting.

But there are reasons why I strive to do my own handsetting and my own illustrations, beyond pride. I find both acts—setting type and carving an image—mentally soothing, almost like a meditative exercise. I think this is something that newer generations are lacking and perhaps yearning for, that interaction or connection between their brain, their soul and their hands and the rewards of making something that is tangible, affecting and shareable with other humans. That tactile element is very human, and when newer generations’ lives are fully invested in electronic devices, producing work that is incorporeal and existing only in a virtual, intellectual or ideological world that is not tangible, humankind is losing something.

I am also very aware of the environmental devastation we humans are causing, so in an effort to tread lightly I try to avoid the use of polymers or any other type of oil byproduct such as plastics. When I must use polymer plates, I use a professional, local service which hopefully has the proper equipment and disposes residues safely.

Whirligig: You are a librarian and Gaby a health care professional. How do these occupations inform or otherwise affect the work you produce as La Feroz?

Ever: In general, my profession has positively affected and sustained my inclination toward writing and art making. Being surrounded by books, and people who value books, is a great experience; and in addition, I consider my having access to millions of library materials as both a privilege and an advantage that I have always valued immensely.

My profession also informs my art practice in several ways, but particularly stylistically and generationally. Working for the Special Collections unit often allows me to see beautiful examples of early printed books. At the same time, I also get exposed to contemporary printers, artists and bookmakers’ works, so these contrasts allow me to see and appreciate both the ancient and the modern worlds of book production, including the visual and graphic arts development.

Gabyâ’s profession is like a thermometer which tells us the temperature of the neighborhood. Her language skills make her connect with her patients and, in spite of the time limitations; she is able to get the pulse of the people when it comes to the concerns, the needs and the cultural connections. We both hope to do more with La Feroz Press for our community, and eventually get people involved in letterpress and relief printing to share and expand the arts to the people.

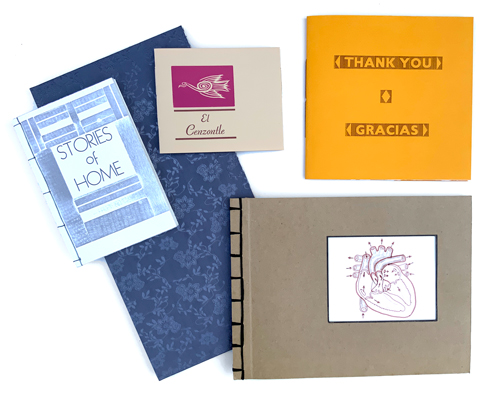

We have done a couple of fun booklets that deal with medical stuff. One was a diagram and description of the heart. The other was a special photo book we did to thank a big donor who benefited a UCSF Nursing Program on diabetes, from which Gaby got a scholarship. When the donor received her copy, she recognized that it had been done in letterpress. She was both surprised and moved by the small book and its contents, which included photos of the very individuals who had benefitted from her kindness.

Whirligig: You are also civically engaged in several local leadership positions which require substantial time commitments. Why do you do this? What do you get from it?

Ever: Let me try to untangle the question of why, because indeed, doing community work can take a big chunk of my time. And I realize that such time put into my community is time taken away from what is personal and dear to me, like spending more leisure time with Gaby, reading and writing, music, and letterpress printing.

But ever since my arrival in this country Need and Give have been my companions. They have come to meet me, constantly seeking out my actions. Even during my humble beginnings as a farmworker in this country, when I would not think I could possibly help anyone, I remember helping folks to read or to write letters to and from their loved ones, helping them to resolve an issue with their bank, at the DMV or the post office, interpreting or filling out a job application or an immigration form, and even doing haircuts and other mundane stuff that people need help with. Back then I was very young and I helped others unconsciously, automatically responding to the demands of Need and Give, because I was a natural problem solver who became the de facto handy man.

When I moved to the Bay Area, I started volunteering more formally in one place or another. This time I was actually seeking out those volunteering opportunities more consciously. At first I did it thinking that I could help or benefit others, but after a while I discovered that volunteerism actually was doing more for me than what I was doing for others. And this responds to your question of what I get from it.

Through my volunteerism I have experienced not only the best in human goodness, but I have also met some of the best people in my social circle. Through my volunteering I have been helped to connect, to find opportunities, to grow, and to thrive in general. Subsequently, civic engagement and activism happened to me through volunteerism and also due to my geographic location. Living in North Fair Oaks has given me a bitter taste of human neglect and has also made me aware of the inequities that exist. So now when I can, I stick in my spoon and try to stir the pot to make the soup more flavorful with a pinch of equality.

Finally there is a personal interest that I have in people and their stories as a writer. I know for a fact that my community work nurtures my writing, my music and my creative life force through experiences that I would otherwise not be having. I think that without my community work pulling me on all sides, outside of my stagnant bubble home, I would probably be a more boring individual doing his reading and his writing with a lukewarm coffee and neither affecting his surroundings nor being affected by them.

Whirligig: You mention that you were a farmworker when you came to California in the 1990’s, and now you are a Stanford Librarian, a respected letterpress artist, and engaged in local community politics. There is a story here. Will you tell us?

Ever: As this story could easily become a book, I will tell only the major stepping stones: In looking back to the path I have chosen, I can see two constants: One has been curiosity, and the other one has been a passion for learning, and for me that order has been effective. My curiosity has challenged me and I have properly responded to that curiosity by exposing myself to learning, formally and informally, from schools and from people, on my own, and from life through experiences.

Having finished high school in Mexico, young and foolish, I was at a crossroads where I felt like I needed to live life and experience it more fully before committing to adulthood, which back then the only prospects were settling on a job, marrying and dedicating one’s life to raising a family—all things for which I was not ready.

Through a clumsily planned event that involved a friend’s invitation to the USA, I found myself in travel and trouble and becoming an undocumented young man trying to survive his chosen adventure. Farm work seemed the only alternative for survival and I took it eagerly in the extreme weather of Arizona, confident that there would be better opportunities for me eventually. I remember coming back home from a full day of back-breaking work to eat something, take a shower and then head out to look for English classes. I was curious about the US culture and language and it seemed natural to me to pursue learning. My roommates and co-workers thought I was crazy and they constantly asked me if I didn’t get tired. Of course I did tire, but I also anticipated the trappings of easy paths and neglect and I decided to drag myself out to continue learning and building a springboard.

Fast forward a few years and I found myself working in the fields of California in search of better wages, better weather and better opportunities. By then I had obtained a work permit, and that along with already having some command of the English language opened my alternatives. I decided to move to an urban setting where I could find better alternatives and opportunities. I came to the Bay Area and settled in Redwood City after finding a job as a truck driver’s assistant. Now the possibilities seemed endless as there were several community colleges that offered formal classes and programs. I attended Cañada College and Foothill College, and eventually I went to San José State University for a bachelo’s degree. My love for books and writing allowed me to find a part time job at a corporate library in Palo Alto. This was the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (the place where the desktop, the mouse and other modern computer devices were invented). Enjoying the library environment and work, I decided that I wanted to continue working in libraries. Eventually I did my master’s degree also at SJSU in Library and Information Sciences. By the time I finished my master’s degree I had already been working in libraries, so my transition to my current job at Stanford was easy and seamless.

This is an oversimplified statement of decades of hard work intermixed with good and awful experiences, including living in the fringes of a society with an unfamiliar culture. But through it all there is a background of built up resiliency that is the backbone of my personal history, which is representative of many immigrants in this country. I am certain that such resiliency and experiences are a source of wealth that ends up benefiting this country and culture with the innovation and renovation that provides an edge in nearly all aspects of a society. What I am or what I am doing these days that benefits my community and society, is only the result of that resiliency combined with the recognition that this is now my home and that there are conditions that need to improve in the various areas that I am involved and active.

Two poems by Ever Rodriguez

Muñones No olvido, simplemente ignoro. Y como el árbol mutilado Que su frondosa sombra extraña, Yo extraño los buenos tiempos —hoy muñones hechos a tajadas. Círculos secos, venas cortadas, Cicatrices como orejas del dolor, Marcas de experiencias ya frustradas, Huellas concéntricas del sufrimiento, Vidas dolorosamente mutiladas. Heridas frescas aun por dentro, Visibles llagas del tormento, Huellas de felicidad truncada, Memorias de lo que un día fueron Las frondosas, verdes ramas. No olvido, simplemente ignoro, Con el anhelo de retoños verdes, Y en espera de una primavera sana Que adorne los muñones agrios De este portentoso ser sin ramas.

Stumps I don't forget, I simply ignore, And as the mutilated tree Misses its shadow, I miss the good times —today's stumps of tedium. Dry circles, veins slashed, Scars like ears of pain, Marks of frustrated experiences; Suffering's concentric signs, And sorely mutilated lives. Wounds still fresh inside, Visible sores of torment, Traces of truncated happiness, Memories of what once were Leafy and greener branches. I don't forget, I simply ignore, Longing new, green sprouts, Awaiting for a healthier Spring To adorn the hideous stumps Of this grand, boughless tree.

Volar sólo por volar ¿Para dónde van, hermano mío, todas las aves que vuelan? Pues verás, Unas se van a asolear, o sus alas a estirar, y a buscar aquello que no aciertan encontrar. Otras se van a cagar, porque el baño no lo encuentran en ninguna parte donde están. Pero las que más me gustan, son las aves que sin prisa vuelan sólo por volar; porque saben apreciar, el que tienen alas, y un cielo ancho, lleno de aire y libertad.

For the Sake of Flight Where do they go, Brother of mine, all the birds that fly? As you'll see, Some go to take the sun, to stretch their wings, or to seek out that which they cannot easily find. Others simply go to crap, for latrines they cannot find near the place they occupy. But the birds I really like are those that without rush fly simply for the sake of flight; because they realize that they have wings and ample sky filled with air and liberty.

Photographs courtesy of Ever Rodriguez and Kent Manske.

Whirligig Interview by Nanette Wylde.