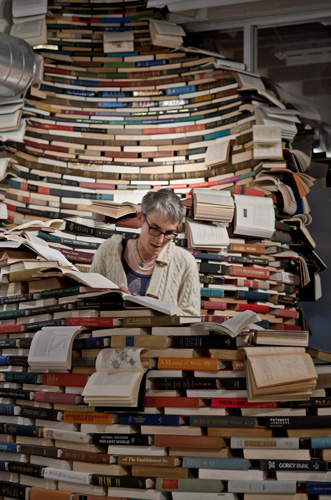

Minoosh Zomorodinia is an Iranian-born interdisciplinary artist and curator working in time, space and the natural world. Her current art practice involves nature walks which are documented via smart phone app. The resultant maps are then made tangible via a variety of both old and new technologies. There is an edgy, accessible humor in much of her work, this she calls “the abstract absurd.” actuality, Zomorodinia uses all aspects of her making to parse and comment on current critical issues including borders and territories, colonialism, immigration, culture and identity, stereotyping, relations of the self to the environment, the power of technology, and the art world itself. Her work is both layered and engaging—smart, funny, and often visually exquisite.

Zomorodinia earned an MFA in New Genres from the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). She has a Masters in Graphic Design and a BA in Photography from Azad University in Tehran. She is the recipient of a Southern Exposure’s Alternative Exposure Award, a California Arts Council grant, and a Kala Media Fellowship Award. She has received residencies at Headlands Center for the Arts, Ox-Bow School of Art and Artists’ Residency in Michigan, I-park Foundation in Connecticut, Local Language Residency in Oakland, Santa Fe Art Institute Residency, Djerassi Residency in Woodside, and Recology in South San Francisco. Zomorodinia has exhibited locally and internationally. She volunteers for Southern Exposure Gallery’s Curatorial Council and is a board member of Women Eco Artists Dialog. Zomorodinia currently lives and works in the Bay Area.

We spoke in the studio at Recology, where Minoosh is resuming an artist residency interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Whirligig: A great deal of your work has a focus on the body in nature—often your own body which is shrouded, wrapped, blanketed, responding to external elements. Why the body? Why your own body?

Minoosh: There are different reasons to use the body in my work. First, I want to acknowledge that my friend, Tara Goudarzi, generously accepted to be a model for the Destruction of Nature, Destruction of The Human Being as we were traveling together.

One reason to use the body is expressing self. I spend a lot of time in nature, it’s an extraordinary experience and inspiration for my practice. My mind opens and I see things when I’m in nature. I search for spirituality in nature and some sort of psychology for finding positive energy. I have been wanting to illustrate this feeling in different ways.

Another reason is to dematerialize and use my body as a signifier to lived experience as well as illustrate identity. I believe using my body offers a variety of contexts and perceptions. Employing my body in my work somehow represents time and space, especially in my performance installations. I consider my body as a sculpture—I make myself vulnerable to challenge the perception of the female body, and represent culture and religion. I want to emphasize a political perception from a Muslim woman’s body and how it’s been interpreted in the world.

Whirligig: Are you thinking of specific interpretations of a Muslim woman’s body? Can you explain?

Whirligig: You were born and raised in Pittsburgh. Can you tell me a bit about your upbringing and family life.

Whirligig: You were born and raised in Pittsburgh. Can you tell me a bit about your upbringing and family life.