Michelle Wilson is a papermaker in an extremely complex sense. Her work with paper is both conceptual and concrete as it extends from the making of sheets for artist’s books and printmaking to social practice, sculpture and installation. As a somewhat recent transplant to the Bay Area, Wilson has quickly embedded herself and her work into the consciousness of the local art scene with a residency at the School of Visual Philosophy, a Small Plates commission from San Francisco Center for the Book, teaching at both San José State and Stanford, engagement with a handful of arts organizations, and many exhibitions.

This summer, Wilson’s collaboration with Anne Beck, The Rhinoceros Project, travels to the Salina Art Center (Salina, Kansas), Shotwell Paper Mill (San Francisco, California), the Healdsburg Center for the Arts (Healdsburg, California), and later this fall to the Janet Turner Print Museum in Chico, California. Her work is included in The Power of the Page: Artist Books as Agents for Change at the New Museum of Los Gatos (NUMU in Los Gatos, California), and Pulp as Portal, Socially Engaged Hand Papermaking at the Salina Art Center in Salina, KS. Wilson has a BFA from Moore College of Art and Design, and an MFA from the University of the Arts, both in Philadelphia.

We got together on a lovely spring afternoon towards the end of the semester to talk about art and teaching.

Whirligig: I first became acquainted with your work in 2010 at an SGCI Conference in Philadelphia, occurring at the same time as Philagrafika, where I came upon a Book Bomb intervention in a public park. How did this collaboration with Mary Tasillo come about?

Michelle: Book Bombs began as a question I posed on Facebook. I was reading about yarn bombing, the tradition of knitting or crocheting something that is then bombed— left in a public space—a form of craft meets street art. I’m not a knitter or a crocheter; I’m a book artist, and so I posted a status update, “What would it mean to book bomb?” Mary took me seriously, and through our conversation, we discussed where people read in public space, who owns public space, and it led us to the idea of park benches. In Philly, every park bench has this center bar installed that is called the “arm rest,” but is designed to prevent a homeless person from sleeping comfortably on a bench. This seemed like an ideal place to install a book. Our project grew from this initial idea. And thus, Book Bombs was born.

Whirligig: What were you envisioning regarding the scope and effects of Book Bombs?

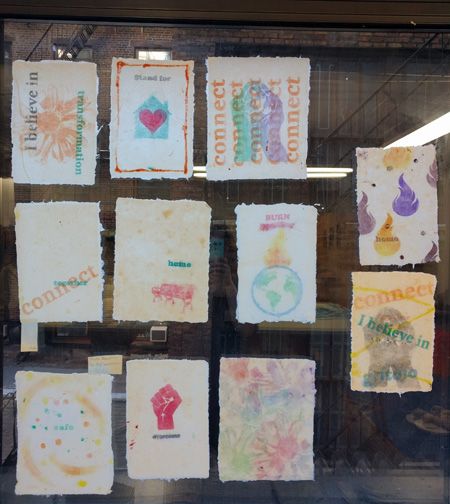

Michelle: We originally saw Book Bombs as just a project for Philagrafika 2010. However, we’ve had so much fun, we’ve continued. It’s been tricky to keep it up transcontinentally, but we manage. Most recently, we did a sort of intervention-workshop at the Center for Book Arts in New York called Keeping the Fire Alive. This was designed as a workshop for activists who were interested in using papermaking in their work, as well using it as a form of self-care against fatigue and for continued resistance. We’d originally proposed the workshop during the summer of 2016, before the election, thinking it would be a very different conversation.

Whirligig: How is papermaking used for self-care?

Michelle: When we were at the Center for Book Arts we were working with people who identified as activists and not as artists. So I think it worked as self care for them. It allowed them to have a creative activity and to feel powerful. I think there is something essential about paper making in that it is from the earth, you are dipping your hands in water and it is plant material—it is this very elemental action. And we are using it to make something that allows people to tell their story or express an opinion. So it connects to both sides: working with the earth and that groundedness of being from the planet, and being in conversation with and connected to community. It is also a productive thing. It is a nurturing process.

Whirligig: Do you think it is different than other creative forms that are therapeutic?

Michelle: The way we were doing it, at that workshop, we took the struggle out. Everybody could get very sophisticated, tangible results. So in that situation, the people we were working with needed that release and that satisfaction. I do think that other art forms have value as self care. Paper making is just so nurturing.

Whirligig: This has me thinking that we are so removed from the process of living. We go out and buy anything we need which is mass manufactured. In earlier times we would go to the papermaker or the cobbler. . .

Michelle: We would sell our rags to the papermaker.

Whirligig: So paper making is a very immediate connection to something we use everyday.

Michelle: Yes.

Whirligig: My second exposure to your work was at another SGCI Conference in San Francisco where you were exhibiting Corn, Incorporated, a suite of corporate watermarked, handmade papers made from corn husk and denim. Tell us about how you came to make this work.

Michelle: I began formulating the idea for Corn, Incorporated when I read The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan while moving across the country. It was riveting to drive across the Corn Belt while reading about the affect of all that corn on the American food system. This idea combined with my interest in nontraditional paper fibers and how they contribute to content and meaning, led me to consider making paper from corn husk. I also have always been fascinated by watermarks—they are ghostly marks that exist inside the paper itself, sort of like a secret message or hidden meaning.

After reading The Omnivore’s Dilemma, I realized how overwhelmingly present corn products were in America. However, due to all the ways corn is chemically transformed, it’s something that many Americans aren’t aware of—corn has this clandestine presence in our food and many other products we use, such as diapers, cosmetics, drywall, adhesives, it goes on and on. Corn has a furtive presence in American culture and capitalism, and a watermark seemed to embody this secrecy.

In addition to what corn is to America now, it also has a quaint mythology pertaining to the origins of this country—we tell embellished and misunderstood stories to children about Thanksgiving, in which the Native Americans taught the Pilgrims how to grow corn. Frequently advertising and packaging plays off of this mythology, presenting corn, and farming by extension, as wholesome, patriotic, and family-oriented. This mythology obscures the reality of industrialized agriculture, which consists of single-crop farming and animal production facilities.

This contradictory mythology led me to the idea of using blue jeans as a substrate for the cornhusk stencils. Jeans are part of American iconography, particularly in regards to farming, they’re part of a farmer’s uniform, so to speak. Despite the fact that most jeans today are made in Asia, and that the dyes used to produce their classic blue lead to an enormous amount of water pollution, jeans are seen as quintessentially American.

So I decided to bring all these ideas together, and that’s what led to Corn, Incorporated.

Whirligig: It is a very smart and powerful series.

You work in a fairly broad range of art genre: print, papermaking, books, installation, social practice, collage, sculpture. Is paper the fiber that holds these together?

Michelle: I would say paper is usually the impetus for how I begin either a work or a project, so in that way, yes, it is something that links the multiple art genres in which I work together. Like most papermakers, paper to me is more than just a substrate or surface; it’s signifier, substance, and content.

For example, for several years now I’ve explored using invasive plants as a basis for handmade paper. This makes a part of my studio practice a means of clearing space for native ecology. One thing invasive plants do is drive out diversity and create monocultures. In this, I see a reflection in Westernization and how it creates a homogenization of culture through capitalism. These ideas led me to use invasive plants for the handmade papers in my book, Future Tense, which is a narrative about the loss of diversity regarding animals and language.

Whirligig: This is the abaca book with the pages flying out (at NUMU)?

Michelle: No. That book is from grad school. Let me connect the two.

When I was in grad school I went to Argentina for the first time with my Argentinian husband. I became very close to two of his cousins and we began a correspondence. I ended up making work about the correspondence. It led me to thinking about what connects us. The cousins were people who did not speak English and who are very different from me. At the same time, they are very much the same. We connected because we have the same sense of humor. . .

When I was in Argentina I saw a reproduction of a painting called South America United by its Rivers. It was South America without boundaries. Usually we think of rivers as lines of demarcation, but I liked the idea of rivers as unification. I started thinking about other things that are naturally unifying.

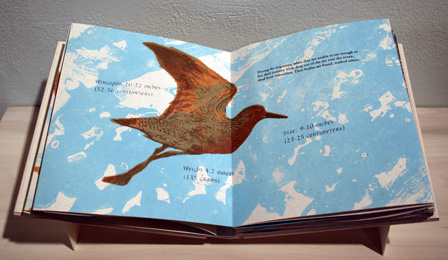

One of the other people I was in grad school with was a very serious birder. We were talking about migration patterns and how these could be a unifying force. There is this endangered bird (that gets a lot of attention) called the Red Knot. It is a long distance flier. It migrates from Tierra del Fuego to the North Pole. It has a stop over in Brazil and a stop over in the Delaware Bay area. It flies for two weeks straight with only those two stops. It stops and eats for two weeks until it doubles its weight, and then it flies. They eat horseshoe crab eggs, which are also used for fishing. So there are a lot of issues, and protections are in place. I think they are down to something like five or six thousand in numbers. They don’t know if this species is going to survive. I was thinking about this bird and ended up making work about this story.

One of the books in my thesis was about this migration. Another was about Argentina’s dirty war.

During the 1970s Argentina was under this military regime which was disappearing people. If people were doing anything against the government, or if the government didn’t like you, they would basically come to your house in the middle of the night, take you from your family, and you would never be seen again. The whole history is not known yet. A couple of the military guards have come forward and said that they would take these people up in planes and fly them over the South Atlantic. Then they would cut their stomachs open and throw them out of the plane into the ocean while they were still alive. Because they were bleeding, sharks would come and take care of the problem. There would be no bodies, usually. But a couple of bodies would wash up on shore. They don’t know how many people this was done to.

Whirligig: This is excessively gruesome.

Michelle: Yes. I’m sorry. So why I was thinking about this in relation to the Red Knot is that they are long distance fliers and are having problems with their food supply so sometimes they starve to death while in midair and fall out of the sky. So I was thinking about flying and falling out of the sky. I ended up making work about this that led me to that piece that is at NUMU right now, which is a little more abstracted. It is about witnessing. It is about a book binder that finds a book and the narrative is about repairing it. They are sewing the signatures together and sort of reading the book. The narrative is going back and forth between bird extinctions and extraordinary renditions (which was a Bush thing) and disappearances. So it is basically about being a witness to history and how it can be very horrifying, but there is this responsibility to watch it and preserve it.

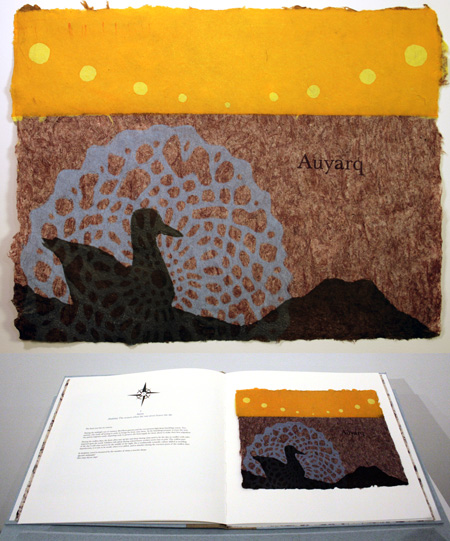

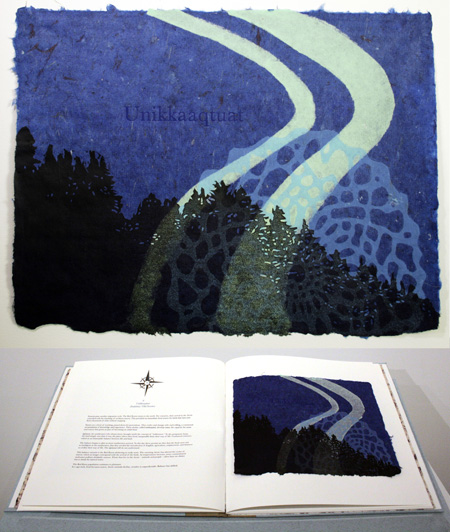

But I was still thinking about the Red Knot and about extinction, and the extinction of languages.

In Tierra del Fuego there are indigenous people there called the Yamana. They are down to their last speaker of the language. I began doing research on Inuit languages. They have actually done a lot to preserve them. Their big threat is climate change. If the ice caps melt they will have to disperse and they might lose their language that way. Between all these ideas I made Future Tense. The Yamana are a seafaring people. There is a theory that they don’t have a future tense (linguistically) because their lives were so uncertain they couldn’t see the future. I’m not sure how accurate that is, but I liked the mythology of it. It’s interesting because we are at this point right now where we have global warming and the people who are most affected are the people who are struggling the most. I was trying to tell that story but through the lens of a bird migration.

I started that book in 2008 and finished it in 2014. I felt that I had to do the research and get it as accurate as I could being a person who is not from those cultures.

Whirligig: The pacing and placement of the text on the pages seems particularly significant in this book. What were you thinking about when designing this?

Michelle: I was trying to set a mood, and the placement was about having the most impact. I wanted it to be very sparse and to create an immersive environment where you are surrounded by these paper forms that suggest birds flying into the book, or out of the book. It had a meditative approach.

Whirligig: What is it about papermaking that attracts you?

Michelle: For me, papermaking is always an act of collaboration. The resulting paper isn’t just because I dipped a mold and deckle into a vat and pulled a sheet, it also needed carbon dioxide, the sun, rain and minerals in the soil to grow the plants that provided the paper; I collaborated with nature itself to make paper. All paper is made from cellulose, which is just a polymer of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms (C6H10O5)—elements that were created in the Big Bang—and water (H2O), a compound of more hydrogen and oxygen. Because of this, the origin of each sheet of handmade paper is an elemental connection to everything in the universe.

Whirligig: That is an enormous, widely embracing way in which to view your media.

Michelle: (laughs) It grounds me. I think every papermaker has this experience. When I was living in Richmond I made paper from growing my own flax. I had this moment when I thought, This is here. This ground, the sun. . . I planted the seeds and I watered them, but this story of this paper isn’t just mine. I had to acknowledge that I am working with something that is so connected to the rest of the universe. It wouldn’t exist without these elemental things. This is what I feel when I have my hands in a vat of chaos.

Whirligig: It’s interesting that you think of yourself primarily as a papermaker.

Michelle: Yes, because I trained as a printmaker and printmaking is still a big part of what I do. Paper making is what connects me to the universe.

Whirligig: There is a strong thread of environmental activism in much of your work as well. . .

Michelle: Underneath everything, I’m interested in transformation and interconnection. This leads me to investigate systems of how environmental justice and social justice frequently are in unison. Frequently, environmental issues, and their solutions, are seen as something for people with privilege. However, for many low-income communities, such as Flint, Michigan, or the Fruitvale neighborhood of Oakland, in addition to their struggles for economic justice, are often threatened by contaminated water, air, and soil.

Whirligig: Are there projects in the works on the issues of these specific communities?

Michelle: Not yet. I did a project last year that wasn’t specific about these neighborhoods but it came out of watching the homeless population. This tent city on Division Street was justing exploding. I couldn’t get over the fact that it was called Division Street. Then the Super Bowl came and the city kicked them all out. At the same time I was listening to the news which was all about Syria and refugee camps. I started thinking about how the homeless are economic and technological refugees of America. If you are a veteran or are transgender, or are somebody who lost your job and became homeless, all of this is because of certain factors that are not in your control. It is the same for people who are fleeing Syria because it is so dangerous, but it is out of their control. I was trying to figure out how you can imprint empathy.

Whirligig: What are some of the challenges of making politically activist art?

Michelle: I don’t know if there is a challenge to making the work per se, I think the challenge is more in getting it out there and having the courage to show it to an audience that may disagree with you. I think there are times when I’m branded as a troublemaker, and some institutions are a bit nervous to show work that might offend someone, although that seems to be shifting since the 2016 election. However, it’s important to remember that work that creates dialogue is successful, even if it’s uncomfortable or unexpected, because that means people are thinking.

Whirligig: Agreed. Currently you are working on a project based on Durer’s Rhinoceros. This project includes sewing circles. Tell us about this.

Michelle: The Rhinoceros Project is my collaboration with Anne Beck, who is an artist and papermaker who lives in Mendocino. For this project, we are conducting participatory sewing circles to create a life-size version of Albrecht Durer’s Rhinoceros in embroidery. This embroidery will be used as the basis for an edition of watermarks in handmade paper.

This project came about through conversations with Anne on Facebook (all my best collaborations have started as conversations there). I was interested in the idea of watermarks as a form of supernatural imagery, and had been thinking about Durer’s print in the wake of the declaration in 2011 of the extinction of the Western Black Rhinoceros. Similarly, Anne had has some conversations while teaching about inspiration and Rhinoceri. This led to the two of us talking about ecological value, absurdity, papermaking, colonialism, and imperilism.

The rhinoceros on which Durer based his print was a gift from a Indian sultan to the king of Portugal. When the animal arrived in Europe, it was the first rhinoceros seen there since Roman times, and it led to a resurgence in belief in the writings of antiquity, such as those of Pliny the Elder. In order to curry favor with the pope as he expanded his empire in Asia, the king of Portugal decided to re-gift the rhinoceros to the Vatican. However, on the voyage to Italy, the ship sank, and the rhinoceros, chained to the deck, drowned. Durer actually never even saw the rhinoceros, he based his work on a sketch and a description. There are several inaccuracies in the print. Yet the image became so well known, his work became emblematic of what people believed a rhinoceros looked like. It was actually used in textbooks in Germany until the 1930’s.

Durer’s image was incredibly influential—an image based on it is on the doors of the Pisa Cathedral, and the Medici family even incorporated it into their family crest. The woodblock Durer carved was printed approximately 5000 times during his lifetime, and probably printed around 10,000 more after his death. Artists such as Salvador Dali and Niki de Saint Phalle have created sculptures that reference Durer’s print.

This history led us to discuss making a watermark of Durer’s print, with the idea that it echoed the extinction of the Western Black Rhinoceros—the idea was as if the print itself had vanished from its paper, and only a ghostly image remained.

Our conversation continued. I’m afraid I can’t pinpoint exactly how we came up with the idea of life-size embroidery as our watermark matrix, but it somehow came about during the Dard Hunter conference of 2014 here in San Francisco. But it was at that event that this idea coalesced. We spent about a year doing tests, materials research, planning, and proposing the project to institutions. However, we kept getting rejected. So we revisited the idea of completing the project at a single location, and decided to adapt it to a traveling project with different communities. With this in mind, we officially launched the project at the 2016 San Francisco Center for the Book’s Roadworks Event, where we had our first sewing circle.

Since then, we’ve traveled to Ramon’s Tailor, an alternative arts salon in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, where we were Artists-in-Residence for November 2016 – January 2017. We also participated in the Kala Art Institute’s Print Public event in March. We’re looking forward right now to being part of Sierra Nevada College’s Steamroller Print Festival in April, a sewing circle with Pacific Textile Arts in Fort Bragg, and in June, we’re traveling to the Salina Art Center in Salina, KS, for some sewing circles offered through their institution in partnership with the Rolling Hills Zoo. We’re going to offer a sewing circle in their Rhinoceros barn, near their three living, breathing rhinoceri!

Another interesting and unexpected thing that arose during this project is the number of people who have asked us why we are doing this. I think it just seems so completely bizarre people can’t help it, especially because they are seeing it in progress. This led us to the idea of making a zine to accompany the project that encapsulated all the complexities and relationships we saw in this project. The Codex Book Fair was coming up, so we set that as our deadline. We decided to do this only three weeks before that event, so the pressure was on. The zine, How the Rhinoceros, is based on the idea of a constellation, and maps the interconnecting history and philosophies of colonialism, imperialism, ecological value, scientific knowledge, and understanding that surrounds Albrecht Durer’s print and how it led to our project. The covers are handmade rag paper, with threads from the embroidery trimmings from our watermark included.

The making of this project is of equal importance to our final product, and the most thrilling part of this project is people’s reactions to participating. Primarily, there is the pleasure experienced while sitting and sewing with friends—however, this is often followed by a sense of ownership of the project. After participating, many people are eager to help us find a way to continue, and suggest possible partners. As the Rhinoceros Project continues, a community is growing. Like the constellation in our zine, this community is literally bound together with the threads of that make up the Rhinoceros watermark embroidery.

Whirligig: How will you turn the embroidery, which is very large, into a watermark?

Michelle: We’ve done tests! It is a modified Tibetan, Southeast Asian style of poured paper. The rhinoceros is 7 by 9 feet. It’s life-size. We are working on a modular frame, so that we can do the pours at different sites. We will pour the pulp right on top of the embroidery.

Whirligig: And it doesn’t stick to the embroidery and wreck it?

Michelle: No. A little bit of fibers might stick, but it works. Right now we are going to make three because there are three white rhinos left in Kenya. When we started this project there were five, and we were going to make five, but now there are three.

We are hoping to sell them to support one of our partners, the International Rhino Foundation. They do research and support for rangers who guard the rhinos. The idea is that we will feed some of the funds back into that.

Whirligig: Did you hear that South Africa just opened up the trade in Rhino horn?

Michelle: Yes. I don’t know how to feel about this. I don’t really know enough. There are arguments for both sides. Some are hoping that it will stop poaching because there are people who raise rhinos. The horn is like our nails and can be harvested without killing the animal. It grows back. I think poachers kill the animal because it easier than tranquilizing them.

Whirligig: You are also teaching at a number of Bay Area Universities and Art Centers. Can you talk about engagement and interaction with today’s art students?

Michelle: Currently, I’m teaching printmaking at Stanford and San José State University, which have very different populations. However, a commonality that I see throughout is an interest in social justice. Students today are much more informed than I was when I was as an undergrad, and they are passionate about making the world better. They are super motivated towards activism, organizing, and using art as dialogue for social change. They’re just as confused as everyone else as to how to do that, but they give me hope.

I like the mental challenge of teaching. It feels important. I need to feel like what I do every day matters.

Whirligig: What is going on with the large scale hanging paper experiments?

Michelle: The paper sculptures are tied into my time at the School of Visual Philosophy (SVP). Last fall, they invited me to do a residency there in paper sculpture. They also gave me a stipend so I could afford to do the residency! However, the greatest thing about the residency was that they didn’t want me to plan a project, they wanted me to experiment, and even said it was okay that if everything I made was a failure. It was a bit scary at first, and I’m still figuring out what these sculptures mean in relation to my more largely narrative-driven work. And I’m also not sure if having to adapt one’s vision as an artist to something completely new is scarier than the original risk.

Part of the residency was also to co-teach a class with Yori Seager, who co-founded SVP and is a traditionally trained sculptor. Yori is very interested in developing a teaching methodology that incorporates teaching questioning and meaning into learning process. Teaching with him was really great, because as someone who teaching a lot of process-driven classes (printmaking, papermaking), often you get caught up in making sure everyone knows what they’re doing and don’t get to consider content till later. But with Yori there, he brought up questions about meaning as we were working. So this way, the students considered the significance of what they were doing and its possibilities as they were learning process.

Even though my time at SVP is up, I’m still working on the sculptures, trying to figure out where they’re going, and how to integrate them into my overall body of work.

Whirligig: What brought you to the Bay Area?

Michelle: I originally moved to the Bay Area from Philadelphia with my partner, who had an opportunity out here. However, I would say living in California really has an affect on a person, and it’s certainly changed both my studio practice and me. I’m very influenced by the landscape around me, and the colors and wide-open spaces of California have certainly infused my work.

Whirligig: How so?

Michelle: When I was on the East Coast a lot of my work was very contained and boxed in. In an East Coast city there is a geometry, and the sky is a strip. When I first moved here the sky seemed so big. Things grow here all year round, and bloom. Even during the drought there was still lots of color. In Philly and New York at this time of year it can be very gray. There is a certain sense in California of re-invention. I think Californians feel like they can reinvent themselves. You can just plant. Even in a broken sidewalk something finds a place to grow there.

Whirligig: How did you become involved with papermaking?

Michelle: When I first saw it as an undergrad I thought is was so amazing so I took a couple of workshops in how to pull sheets. When I went to grad school I made sure it was somewhere that had paper making. There is so much to learn just to make sheets. When I began it was about making perfect sheets. Then there are the What if questions. And the what does it mean if questions: What does it mean if I use recycled materials or if I use pure abaca? What does it mean if I grow my own fiber. What does it mean if the sheets aren’t perfect. It is this constant expanding thing of potential.

Whirligig: If you were not a papermaker what would you be and why?

Michelle: I think I would still be a printmaker. I think I have always been drawn to process based arts. I loved clay as an undergrad. That might have been a direction that I would have gone. I remember painting and thinking I was suppose to be a painter, but my mind wouldn’t be focused on it. My mind would be elsewhere. I think I like processes that require me to move. I need to engage my body.

Photos by and courtesy of Michelle Wilson: El Proceso at NUMU (photo by Robert Wuilfe); Book Bombs; Corn, Incorporated; Vueles; Vueles; Future Tense; Future Tense; Rhinoceros Project sewing circle at Kala; Rhinoceros Project sewing circle at Ramon’s Tailor; Division, installation view.