C.K. Itamura is an interdisciplinary artist, designer and producer. Her work responds to a wide range of personal and social content; and is realized as richly engaging, metaphorically layered, participatory, conceptual installations. C.K. is Director of Marketing and Events for San Francisco Center for the Book and a board member for Healdsburg Center for the Arts.

Her most recent work s+oryprobl=m is a three part series of exhibitions which may be experienced at: O’Hanlon Center for the Arts, Loft Gallery in Mill Valley (June– July 2017); The Spinster Sisters in Santa Rosa (April–June 2017), and City Hall Council Chambers also in Santa Rosa (thru May 4, 2017).

We chatted over an early evening cup of tea in mid April.

Whirligig: You are making and exhibiting complex, multi-layered, series of works that are highly metaphorical and cross media distinctions. How would you advise new art audiences to approach and experience your work? What do you hope people will “get” from experiencing your art?

C.K.: I’ll use my piece Ladies (2015) to illustrate your point.

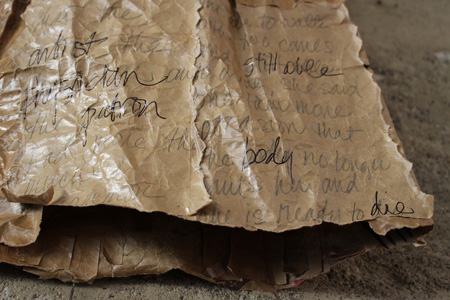

Ladies was inspired by a surreal hours-long conversation I had one afternoon in 2013, with two strangers in an art gallery. One woman was a retired physician with crutches, the other woman was an art patron that I’ve seen at artist receptions but had never spoken with before. Over the course of the afternoon, the retired physician revealed that she wanted to die because her crippled legs prevent her from doing all the things that hold joy for her, such as hiking, swimming and traveling. The art patron revealed that she had lost all of her money and was now living in a van that she had to park in a different place every night to prevent getting into trouble with the police. After the conversation concluded when the gallery closed for the day, I wrote down notes that would remind me of this curious encounter. Two years later, the notes evolved into Ladies, a wall mounted sculpture in the style of a mini-dress that Tina Turner wore on stage during a performance with Mick Jagger on the British stage of the Live Aid Concert in 1985.

Ladies is constructed of torn paper grocery bags; it is a bag dress that suggests the phrase “bag ladies,” term recalled from childhood that was used to describe seemingly homeless women who kept all their belonging in bags they carried with them, from place-to-place, at all times. Ladies is symbolic of contrasts: the facades of the retired physician and the art patron vs. a hidden desire to die and destitution; the opulence of Tina Turner’s memorable performance during a come back era of her career vs. the desperation of forgotten “bag ladies.” Excerpts from the notes I wrote after the curious conversation were written on the paper bag sections in pencil then selected words were traced over in permanent marker. In a final nod to another lady, my maternal grandmother, who hung laundry outside, rain or shine, the inside of the piece is filled with wooden clothes pins that are not plainly visible from the outside, as my grandmother was rarely seen away from her home.

Now, to answer your questions, how would I advise new art audiences to approach and experience my work and what do I hope people will “get” from experiencing my art?—With Ladies, some people may see something that looks like torn paper bags on a wall, others may see the mini-dress shape, others may notice selected words written in marker on it, others may read the notes in pencil written all over the piece, some may even peer inside and find the wooden clothes pins, others may read the title and make associations, while others still may ask for the backstory. There is no correct or expected approach to experiencing my art. The experience of viewing or even being in proximity to my work and viewing it peripherally is the point that connects the viewer to the work and by association to me. I create it, they have some sort of experience with it, we are connected. The experience also creates the opportunity for multiple viewers to be connected to each other through the shared experience, similar to the ways an act of sharing a meal at a table, watching a basketball game at a sports bar, or marching in a crowd in a protest can engender connections. In those places and at those moments connections are established, and connections are the essence of life. The narrative of the backstory is my personal experience with Ladies. Other people will walk away having experienced their own personal interaction with it and they will derive their own narrative about it and may share it if they choose to.

Five people sitting in five different vehicles stuck in a traffic jam on the highway will experience the same traffic jam in different ways: one may miss a flight and be apprehensive of all of the rescheduling they will need to do over the next 24-hours; one may be late for school and be worried they will miss an important lesson; one may spend time listening to the news or to music; one may need to use a restroom and be experiencing physical discomfort; one may spend the time to muse about someone they love. Each individual will have their own personal interaction with the same traffic jam and they will derive their own narrative about it, and may share it if they choose to.

Whirligig: What are you thinking about with the s+oryprobl=m trilogy?

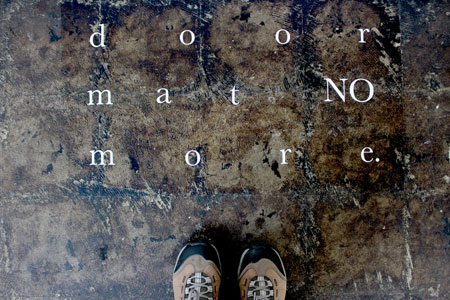

C.K.: After a successful solo exhibition at The Spinster Sisters in 2015, I was invited to have another solo exhibition there in the spring of 2017. In 2016 arrangements were made for solo exhibitions at both the Santa Rosa City Hall in the Council Chambers and in the Loft Gallery at O’Hanlon Center for the Arts to occur in the spring 2017 and the summer of 2017 respectively. I had projects planned for all three exhibitions, but then something unexpected occurred: the turmoil surrounding the 2016 U.S. presidential election and I found myself caught in the storm of the election, the election results and the aftermath.

Immediately after the election results came in, I began work on Great, Fucking Great (2016)—a series of four black flags, some upside down and missing stars combined with a dustpan on the floor—and I completed the project in short order, but afterward, I was paralyzed with guilt for spending time in my studio creating art, as I felt all of my available time and energy could be better spent addressing civics issues, even though I wanted to be in my studio working. I was at odds with myself and I needed to find a way to resolve this issue.

First: I decided to remove myself from my own dilemma and approach the conflict from a neutral perspective.

Second: I decided to take the formula of elementary school story problems and transcribe the elements of my situation into a math problem where the desired outcome would be the determination of the amount of time and energy that could be spent, and mental and emotional toll that could be taken, over a specific duration of time–in this case 1461 days, which is the number of days in a four year U.S. presidential term in office–and be sustainable.

Third: In order to accomplish this I decided that I needed to do something or create something 1461 times so that I could internalize this number. Since drinking a cup of hot tea, chai or sun tea is something I associate with reflection and contemplation, I decided that creating 1461 handmade teacups from tissue paper would suffice.

Fourth: I would determine a sustainable allocation of time and energy, and exact the estimated mental and emotional toll of the endeavor.

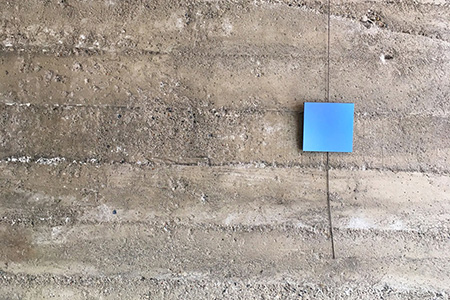

The byproduct of this cathartic exercise became s+oryprobl=m :: fragile vessels, the first installation of the series. s+oryprobl=m :: alternate route and s+oryprobl=m :: x = blue address further predicaments that arose during the creation of the s+oryprobl=m :: fragile vessels.

Whirligig: What is/was the mental and emotional toll of this work?

C.K.: During the process of making all of these 1461 teacups which I was making everywhere–in my studio, in my sunroom, when I would housesit in San Francisco—I was listening to NPR and reading the news, thinking about it. . . so reading and listening to the news ended up being part of the process. I also made some field trips. A notable field trip was to the Veteran’s Memorial Building where there was an exhibition at the San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery that was all by service people, including the Coast Guard. These were current and past service persons who were artists and writers. Everything was unfolding in the news, and I was thinking “Oh my god! We are headed for World War III. Nuclear war. We all have to fight for what is right and spend all of our energy fighting.” All of these things were in my head. That prompted me to make a second field trip to the Rosie the Riveter Museum which is a small little building behind the Craneway Pavillion in Pt. Richmond. They have films and artifacts from WWII about when women had to make the ships and build things because all of the men were away fighting the war. So while I was walking through all of the displays it started to sink into me that not everybody has to be on the front lines.

During WWII there were literally the people who were on the front lines and the people back home who were building the ships and making the weapons, and to take a step back further, and growing the food and making the art. At that point I realized that I don’t have to be on the front lines. I don’t have to spend all of my days writing letters and postcards and organizing meetings and marching every march that I get notification for. That I can exist not on the front lines but on the Rosie the Riveter level, behind the scenes, and offer support in that way. That was a huge realization for me: That I can do what I do and other people can do what they do and every small action multiplies to help in the effort. It was that trip to the Rosie the Riveter Museum that helped me to not feel at odds with myself and to feel good about the work that I am able to do. I was feeling like a dolphin caught up in a net and I was trying to figure out how to get out of the net. This project was how I found my way out of that net. The product was getting back to myself. The byproduct was the physical piece.

Whirligig: Anselm Kiefer once said something to the effect that one has to believe that art can change the world, otherwise it is pure idiocy. Where is that balance for you between making work that is both political and healing and civic action?

C.K.: I’m not operating with the mindset that I intend to make political pieces or create work that will have civic significance. Although, I don’t begin from this point of view things I do may end up that way simply because politics or civic issues are on my mind; I’m really operating on a much more internal level. Often times the byproducts of my processes are community oriented and when they are it is because I personally am grappling with these types of issues, trying to get a grip on them, trying to find something I can do to resolve them, and the results may ultimately have some kind of accidental impact beyond myself.

I didn’t start out making the teacups as an installation work. As the number of teacups grew, they formed a large cloud. Then this cloud of teacups was unintentionally installed directly above the city councils’ heads.

Another example is 5050 constructed of 1000 feet of polyvinyl chloride mounted on galvanized steel pipes which I started because I had turned 50 and didn’t want to be. Although this piece was installed in four different venues, most people observed the piece as a sculptural form and very few ever inquired what the piece was about. Of those who did ask and I obliged, some discovered a common bind with others who had similar apprehensions about or experience with turning 50; they could relate to the piece. The act, the process, the time and effort I spent making it helped me to overcome my apprehension about being 50, and the byproduct of the physical piece itself was something that others found they could relate to. It was similar to s+oryprobl=m :: fragile vessels in that I went through the process of making it and when I completed the piece and came out on the other side of the process I felt that I could live with the situation, and some others have expressed to me their familiarity with a similar initial dilemma of their own.

Whirligig: What were you thinking about with w[o]rdrobe which you exhibited last summer?

C.K.: My original intention with w[o]rdrobe was to bring to light issues regarding consumerism that were weighing heavily on my mind at the time, however, with several friends going through personal crisis, my attention started turning toward their issues and toward reflecting upon my own evolution toward acceptance of the past, present and inevitable, unpredictable future. w[o]rdrobe: Lessons A thru I (2014) was included as an acceptance of the past. Magic Glue (2016) was included as an acceptance of impermanence. Ladies (2015) was included as acceptance of the present. Excerpt I (2015) was included as the desire for immortality. Widows Weeds (2016) was included as an acceptance of death. 5050 (2014) was included as acceptance of the inevitable. 2016 to 2064 (2016) was included as the acceptance of loss. Walk (2016) was included as a call to pay attention to the plight of others.

Whirligig: So what may appear as singular works are actually series of conceptually related projects. Do these thoughts become completed for you with the making and exhibiting of the works or are their threads carried into future works?

C.K.: I am constantly finding patterns in things and when I do I let them morph. Initially with w[o]rdrobe the exhibition was going to be about consumerism, but during the time leading up to the exhibition I had a couple of friends who were going though divorces and another friend who was experiencing major mental health issues. Thoughts about these friends permeated my consciousness and I started creating peaces that were reflected of lifetime experiences of people as they graduate from one experience to another. Ultimately the w[o]rdrobe exhibition ended up having both a thematic and visual tie between wardrobe related shapes—dresses, a dressing table and shoe boxes and the the big 5050 scarf and not being about consumerism.

In some cases an individual work might complete a thought process but in others it might lead to something else, but I won’t know it until I get there.

One piece included in w[o]rdrobe is a piece, Magic Glue (2016) that is made almost entirely out of glue. This piece was created as I was internally processing the divorces of two of my friends and the that I live in Sonoma County which has a huge wedding industry and the fact that some people think that a the ceremony of a wedding itself is some kind of magic glue that will make a couple invincible. In addition to the dress Magic Glue consists of is a large puddle of glue on the floor beneath the dress and two empty bottles of glue in the puddle. The bottles each have a label that says, “Works 50% of the time. Magic Glue comes without a lifetime guarantee.” I had just put the dress on the wall, even with the puddle and the glue bottles, it would not have completed the message without the text. My belief, my commentary, my process of this work arrived at completion when I put this text on the bottles in fine print; this was the moment of completion for that project.

Whirligig: Let’s talk about the metaphors. Where do they come from and what are they expressing for you?

C.K.: Ah, the metaphors! For as long as I can remember, the metaphors–I can remember happily experiencing this when I was as young as three, four and five years old–quite literally feel like quick little sparks or tiny electrical connections happening in my head, synapses in action. I call them “sizzles.” A single sensory prompt–it can be a faint scent of cedar, a taste of curry, a warm pile of laundry, an angle of afternoon sunlight, the sound of footsteps on gravel. It can even be a temperature, such as my favorite one (72 degrees for instance), a degree of elevation or a level of humidity–automatically triggers a probe that retrieves related data stored someplace in my brain and returns the results sometimes with some pomp and circumstance and at other times with no ceremony at all.

It’s like sending somebody into a storage warehouse to look inside the storage units and asking them to bring back anything they can find that is related to tennis. A second or two later they return to you excited with their arms full of these things: two people arguing over whose turn it is to do the dishes, a book about the Cuban Missile Crisis, a desktop-sized model of a pendulum made out of brass, and also a tennis ball, a tennis racket, a badminton racket, a plastic badminton birdie, a real bird, a bird feeder, a sack of bird seed, and one “everything” bagel covered in sesame, poppy and sunflower seeds with a side order of lox and a smear of cream cheese. There I go with the metaphors and associations again! To me, it’s evidence that everything is connected in some way or another, like a big net or a hammock that I can let go, fall into and feel comfortable in. I think poets and fighter pilots might be wired in a similar way, and perhaps improvisational actors and stand up comedians too.

Whirligig: It sounds like you have the gift of not self-editing, the freedom of embracing your own thought flows and the confidence to allow these to feed the work. What is the metaphor of the oyster eating in The Oyster Piece?

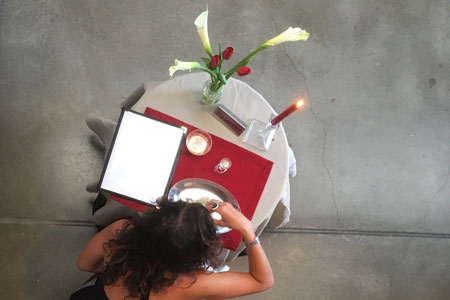

C.K.: I was invited to show a work in an erotic art exhibition. But there is not a single piece I have ever done that would fit in an erotic art exhibition. I haven’t even ever drawn a naked body. I couldn’t just make a work for this show. I just couldn’t do that. It would have to be something that I had already done. The only thing I had was this poem about an oyster that I wrote about ten years ago that has erotic connotations. I had been carrying this idea in my head about how I would perform this poem, I just never did it. So the piece is a performance that involves a Maitre d’, a waitstaff and a chef. It takes place during the reception. People are invited to make a reservation to eat an oyster. When it is their reservation time, they are seated and given a menu, which has instructions. Part of the instructions is to turn the page and read the poem. While they are reading the poem they are served an oyster and champagne. When they have completed eating their oyster, they are given a piece of paper on a small tray; instead of a bill it’s the colophon for this life-size diorama participatory poetry chapbook. We had so much interest we served 19 people. The poem was meant to be played out in this way. The Oyster Piece is an example of a work that may never have been exhibited if it hadn’t been for the invitation to show in this erotic exhibition.

Whirligig: You appear to be exceptionally prolific. How did you come to be an artist and what is in your secret sauce?

C.K.: Rather than art being some sort of profession, I believe that art is a way of moving through time and space and relating to elements. Over time, I’ve come to realize that art isn’t something I need to strive for or arrive at; I’ve been inside it and it has been inside of me all along. I also believe that the purpose of visiting a museum or gallery or exhibition or performance or concert or venue or restaurant is to appreciate the work of others and to pay respect to the artists who create the visual art, dance, music, ambiance, food and drink; and that the act of being inspired–rather than being something that is gleaned from being in proximity or audience to somebody else’s observations, experiences, processes and methods–happens during the course of each of our own everyday lives. Giving some advice to a friend who going through a divorce, a surreal afternoon conversation with strangers, reflecting on relationships gone by, a humorous twisted story, a milestone anniversary, a life too short, riding an urban train, a walk around unfamiliar parts of neighborhoods, mismatched socks, the sky, fear, joy, love: these things and more are all inspirations.

My mantra, my artist statement, my secret sauce so-to-speak is this: whatever works. If I don’t feel like being in my studio or if I don’t feel like creating something on any given day, I simply won’t do it. Instead, I’ll stare at a blank wall, go for a hike, or clean out my car, or pull weeds, or make a pot of soup, or try to play the bass or guitar, or whatever works on any given day. When I feel like being in my studio or creating something that’s when I do it; I do it when I feel like doing it, otherwise it’s a waste of life. I’ve been known to give up sleep, sunlight and social life in order to work on my projects, when I feel like it, and I’m on a roll. I also don’t impose restrictions on myself to work with only a select group of materials and tools. It seems unnecessarily self-limiting to think, for instance, “I’m a printmaker, so I don’t do sculpture.” or “I can’t incorporate music into my work because I am a visual artist.” or “I only work with glue because I’m trying to master glue.” This kind of thought process is stifling to me. Life is short. “You only live once. The sky is the limit. Go for it.” so the sayings go and I wholeheartedly agree.

Whirligig: What is your educational background?

C.K.: I basically graduated from high school, thought I would go to CCA in Oakland but I couldn’t financially make it work. So that was the end of that. I went to work for a bank and became a database implementation consultant for 15 years.

I guess I’m an outsider artist in that way. I took a lot of high school art classes and got to design a bicycle patch when I was in elementary school. I never studied art at the college level. I’ve just always done art in some form, not always visual. It’s been a sort of hands on, ad hoc, make it up as you go along sort of training. I’ve always been involved in artistic things–music, dance, radio production, theater. I’ve always thought that live events are an art form. I volunteered in a lot of different arts organizations.

One of the projects that I worked on as a database implementation consultant was for the San Francisco Opera. So I was behind the scenes at the San Francisco Opera for a year and a half. It was fascinating. Being in that environment and learning about everything and who did what was so exciting. In all of the offices they had an intercom system so no matter where you were in this maze of offices behind the scenes, you could hear what was going on on the stage during rehearsals. It was such an inspiration. I decided that when I was done with the project I was going to do something different that was fun and that I would love because I don’t love databases. Up until that time I did not know a lot of people who were doing art full time for a living. I just knew people who were doing it part time and struggling. Everyone in that opera house was doing it full time. So I left that job and worked for several different theater companies as stage manager and production manager, and for multiple live event production companies producing large scale concerts, fairs and festivals.

Whirligig: How do you make your living now?

C.K.: Now I work for a non-profit arts organization which is very different than working for a corporation. As the Director of Marketing and Events for San Francisco Center for the Book, I’m working for a mission, for a common good purpose, rather than making money for shareholders of a corporation. People say, “how can you work full time and be a full time artist?” I don’t sleep. <laughs> I’m engaged in art all of the time even if not in my studio. The field trips, the research, the thinking. . .

Whirligig: You are also actively engaged with several arts organizations including the Healdsburg Center for the Arts. How does working and volunteering for arts organizations inform your own work and thinking?

C.K.: Rather than my work and volunteering for these organizations informing my work and thinking, the reverse is true in that I use my work and thinking to benefit these organizations and help them to further their missions.

Whirligig: As a curator what types of exhibitions are you interested in and what are you looking for when selecting artwork for group shows?

C.K.: For exhibitions my radar naturally seeks out honest, authentic work created of the artists’ unique personal experiences.

Whirligig: Which contemporary artists do you find most inspiring or exciting and why?

C.K. Contemporary artists I am excited about–I am careful not to use the phrases “inspired by” or “excited by” here, but rather I am intentionally using the phrase “excited about“—are people I know personally, have interacted with, and appreciate and I do not limit the definition of “artists” visual artists. I recently met Marty McCutcheon whose video work I am excited about. I am also excited about the work Michael Recchiuti does with chocolate, Scott Heath and Ellen Cavalli do with heirloom apples, Isa Jacoby does with produce, Conrad Praetzel does with music, Laine Justice does with stories and paint, Ledoh does with Butoh, Brian Singer does with OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder), Hugh Livingston does with sound and space, and what Spike Kahn does with entire buildings. I could go on and on.

Whirligig: Is your studio actually a peach farm? Do you consider yourself a farmer (of sorts)?

C.K.: The name Peach Farm Studio is an ode to my paternal grandparents who were peach farmers in the Central Valley of California. They lost everything due to Executive Order 9066, the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. After they were released from the internment camps, they found another orchard and began peach farming anew. Although I was born in San Francisco, far from peach orchards of any kind, I do remember trips to the countryside and visiting orchards and fruit stands. I have an affinity for planting, growing, harvesting and preparing my own simple food. In a postage stamp sized garden, growing tomatoes, beans and basil, and making a simple salad or topping for pasta are some of the most personally satisfying things I do.

Whirligig: That naming is a lovely remembrance and homage. The internment of Japanese Americans was such a horrific act, yet surprisingly even in California where it happened, the public does not hear that much about it, at least not until recently. I learned about it as a child from a neighborhood mom, but it was not addressed in any of my U.S or California history lessons, and in my experience, is rarely talked about, unlike some other historical atrocities. It seems to mostly come to the forefront though the arts such as the work of Bruce and Norman Yonemoto or Tamiko Thiel. Did your grandparents talk about their experiences with you? Has this entered into your work?

C.K.: I have two sets of grandparents. My Hawaii grandparents did not get interned. Their experience was completely different and was not affected in the same way. The Californian grandparents were the ones who had to go to the internment camp. My grandfather died before I was born so I didn’t hear any stories from him. My grandmother did not speak English. I don’t speak Japanese. I’m fourth generation Japanese in this country. I joke with people by saying I’m even lucky I can use chopsticks. My California grandparents were second generation, born in Hawaii. Because they were born in Hawaii they never needed to learn English. It was a very closed society. They didn’t need to interact outside of their own neighborhoods. So we never really communicated directly.

My dad and uncles were just little kids when they were in an internment camp and my dad doesn’t really remember very much. So I didn’t get stories from family. I probably learned about the internment camps from the same sources as you did because of the gap in language and in generations. I’ve probably learned more in the last five years because of all of the art exhibitions about it.

Whirligig: It’s not really a part of your work then.

C.K.: It’s not really a part of my work. After the war, when they grew up, my dad and my uncles all went off to the military and then had regular jobs. All they ever wanted was to blend in. With my relatives it was like “That happened and now I’m going to study to be an engineer. That happened and now we are going to move on.” It’s not that it’s a secret. I think it’s more that maybe it’s a cultural thing that you accept that it happened, that you can’t do anything about it, and don’t dwell on it. You find a way to move on.

Whirligig: What’s next?

C.K.: After the third installment of the s+oryprobl=m series, s+oryprobl=m :: x = blue has been completed, I will spend some time writing and sorting. My habit with my projects is to verbally, in person, tell the backstory behind my projects to a few friends and acquaintances who ask me about the pieces at artist’s receptions. However I am increasingly being asked to write the backstories down so that people who aren’t in the same space and time with me can have the opportunity to learn about the backstories too. So, I will be documenting the backstories behind some of my projects created from 2013 thru 2017, and I will sort through the process photographs I took during the creation of many of the projects. These will be compiled into a catalog that I expect to complete during the autumn of 2017.

Whirligig Interview by Nanette Wylde.

C.K.Itamura’s website: www.peachfarmstudio.net

Photos: C.K.Itamura with Walk (2016) and 2016 thru 2064 (2016): Michelle Feileacan Photography; Behavior (2015): C.K. Itamura; Ladies (detail): C.K. Itamura; s+oryprobl=m :: alternate route (2017): C.K. Itamura; s+oryprobl=m :: fragile vessels (2017): Blaze Event Photography; 5050 (2014): C.K. Itamura; w[o]rdrobe (2016) : C.K. Itamura; Oyster Piece, Player #10 (2017) : C.K. Itamura; Oyster Piece (2017) : C.K. Itamura; Remodel (2016) : C.K. Itamura; Big Blue Sky & The Distractions (2017) : C.K. Itamura.