Minoosh Zomorodinia is an Iranian-born interdisciplinary artist and curator working in time, space and the natural world. Her current art practice involves nature walks which are documented via smart phone app. The resultant maps are then made tangible via a variety of both old and new technologies. There is an edgy, accessible humor in much of her work, this she calls “the abstract absurd.” actuality, Zomorodinia uses all aspects of her making to parse and comment on current critical issues including borders and territories, colonialism, immigration, culture and identity, stereotyping, relations of the self to the environment, the power of technology, and the art world itself. Her work is both layered and engaging—smart, funny, and often visually exquisite.

Zomorodinia earned an MFA in New Genres from the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). She has a Masters in Graphic Design and a BA in Photography from Azad University in Tehran. She is the recipient of a Southern Exposure’s Alternative Exposure Award, a California Arts Council grant, and a Kala Media Fellowship Award. She has received residencies at Headlands Center for the Arts, Ox-Bow School of Art and Artists’ Residency in Michigan, I-park Foundation in Connecticut, Local Language Residency in Oakland, Santa Fe Art Institute Residency, Djerassi Residency in Woodside, and Recology in South San Francisco. Zomorodinia has exhibited locally and internationally. She volunteers for Southern Exposure Gallery’s Curatorial Council and is a board member of Women Eco Artists Dialog. Zomorodinia currently lives and works in the Bay Area.

We spoke in the studio at Recology, where Minoosh is resuming an artist residency interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

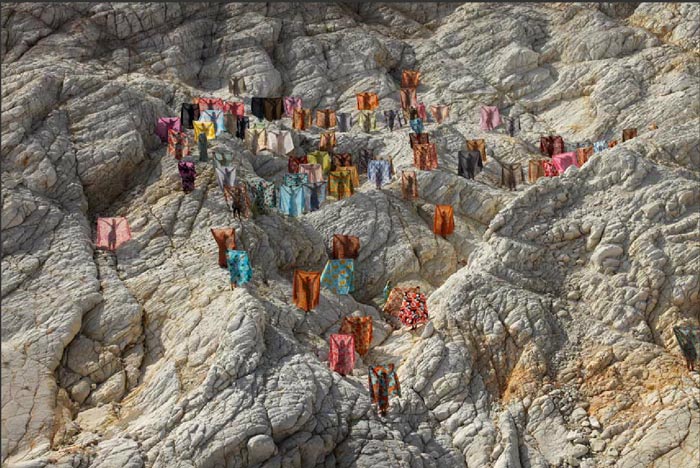

Nanette: A great deal of your work has a focus on the body in nature—often your own body which is shrouded, wrapped, blanketed, responding to external elements. Why the body? Why your own body?

Minoosh: There are different reasons to use the body in my work. First, I want to acknowledge that my friend, Tara Goudarzi, generously accepted to be a model for the Destruction of Nature, Destruction of The Human Being as we were traveling together.

One reason to use the body is expressing self. I spend a lot of time in nature, it’s an extraordinary experience and inspiration for my practice. My mind opens and I see things when I’m in nature. I search for spirituality in nature and some sort of psychology for finding positive energy. I have been wanting to illustrate this feeling in different ways.

Another reason is to dematerialize and use my body as a signifier to lived experience as well as illustrate identity. I believe using my body offers a variety of contexts and perceptions. Employing my body in my work somehow represents time and space, especially in my performance installations. I consider my body as a sculpture—I make myself vulnerable to challenge the perception of the female body, and represent culture and religion. I want to emphasize a political perception from a Muslim woman’s body and how it’s been interpreted in the world.

Nanette: Are you thinking of specific interpretations of a Muslim woman’s body? Can you explain?

Minoosh: I was referring to the works which were performances. A series called Resist, where I am folding the chador, a large piece of cloth that is wrapped around the head and upper body leaving only the face exposed, worn especially by Muslim women. This work started when I first came here. I was newly moved to the United States and I was going to school. I felt so isolated and not part of the community at school. I was experiencing being excluded. I was thinking: I can be a Muslim but I am also a human. I wanted to make a connection with my American fellows who were not familiar with a Muslim body. What I am saying with this work is that one’s appearance creates a form of stereotype that people already have an opinion of. It is about appearance and invisibility. It has become political because it is how it is interpreted. Just by saying “I am from Iran,” in an American context I am considered Middle Eastern and Other. I have been told that utilizing my body in my work is considered political because I am Muslim and I dress in a manner which shows my identity and my culture.

Nanette: Because your choice of dress is identifying?

Minoosh: Yes.

Nanette: Because looking at me one has no idea what my spiritual practice is.

Minoosh: Exactly.

Nanette: It’s an interesting thing.

Minoosh: Yes. I have this argument with people, especially my male friends who are immigrants and from Iran, whose experiences are different from mine. I tell them, “You are not getting any of those impressions from the first look because you are a man, you are not wearing a hijab (head scarf), and people are not afraid of you since you don’t show your religion.”

I’m not sure that this is exactly similar, but it is like how people react when they see a homeless person. Homeless people are invisible because of the assumption of mental illness or whatever is already there. I think stereotypes are there for the Muslim body, especially for women.

Nanette: So, wearing the hijab is creating a political body?

Minoosh: Yes, but it is not intentionally political.

Nanette: And that is a choice that you are making. That is kind of a tricky area to navigate.

Minoosh: What do you mean?

Nanette: Well, you are making a choice to engage in a cultural practice but you are in a different dominant culture where you are a minority in that choice. And that choice could be anything—it could be a braid sticking out of the top of your head or wearing a red shoe on your right foot. It could be anything. But you are feeling erased or invisible because of it. It is like being judged for letting one’s hair turn gray, when one could color it.

Minoosh: But why should I have to do that?

Nanette: So you are saying, why do I have to assimilate culturally to be equal.

Minoosh: Yes. Why do we have to assimilate. Why can’t we be ourselves. That is what I am saying. If we are talking about humanity and that we are all human. Consider how we are with animals and pets. We are okay with stereotyping and being superior to animals, but with nationalities and culture? It is the same thing with transgender people.

Nanette: It’s a form of tribalism. It’s one of the things that troubles me about missionaries—they go to other countries and cultures and tell people they are savages unless they start believing their religion, which is kind of what you are talking about. . . forcing people to assimilate to be accepted.

Minoosh: I’m not forcing people to convert nor am I a missionary, but I do expect respect as a citizen.

Nanette: Wearing the hijab is a political act?

Minoosh: I think so.

Nanette: Why are you choosing to do that?

Minoosh: It’s personal. For me it is because I feel more comfortable. It’s how I grew up. I like how I feel when I am wearing the hijab because I become invisible. People don’t look at me and don’t see me.

Nanette: So you like that and you don’t like that at the same time.

Minoosh: Exactly. I hate segregation and ignorance, but I’m happy that I am invisible and nobody looks at me. At the same time, I don’t like to be ignored. For example, if I try to talk to someone and they leave and ignore me. . . I experience this all the time.

Nanette: Are there additional ways in which your religious beliefs influence and inform your artwork?

Minoosh: I don’t necessarily think that I’m making art that is referencing my beliefs, it’s not intentional, it just shows. It’s because I grew up with it. It’s part of my identity.

Nanette: So what you are saying is that being Muslim is just part of who you are. Is it cultural or is it spiritual?

Minoosh: Part of it is cultural but in my work it is more spiritual. In my work I am using nature. It is very personal. Through the walking I get a lot of signs. It is more about how the mind travels and sees differently. It is a type of spiritual ritual and it is changing. I never had the intention to be a walking artist, but signs came towards me. For example, here at the dump I found a bunch of tapes. How many Muslims do you think would live in this neighborhood? I found a cassette player, turned it on, the tape inside was reciting a surah from the Quran. There are so many things that I am not planning to do, it just comes intuitively. That is how my walking practice started.

Nanette: How is walking art?

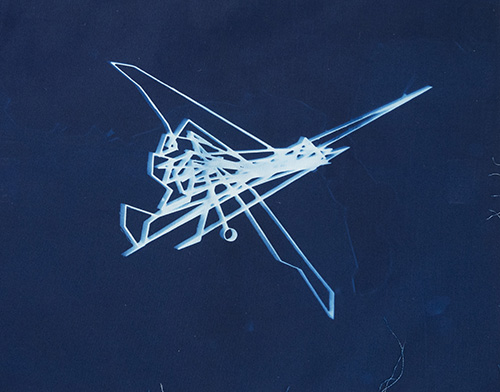

Minoosh: I was first introduced to walking as art by land artist Richard Long. Since I had an interest in nature and ritual, walking as a spiritual action became an important element in my practice.

Before I moved to the United States I made documentary photography. For several years I photographed a special event, Tasoa and Ashora, which is a major religious commemoration of the martyrdom at Karbala of Imam Hussein, a grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. Chel Manbar is accrued once a year in Khorramabad during the month of Muharam on Tasoa. It’s commemorating Imam Hussein, Shia’s leader in Khorramabad, Iran. In this ritual women walk barefoot, silently, light candles on 40 altar sites and make a wish. For three years I traveled to the city to capture this ritual.

My first semester as a student at SFAI I was spending many hours in the film laboratory. We had access to a large archive of 16mm footage. I enjoyed the dark and quiet studio down in the basement. While experimenting with a Bolex 16mm camera and projectors I found a reel which was documentary footage from a Haj pilgrimage, so that became inspiration for my work. There are several rituals in Islam during Haj pilgrimage. One is Tavaf which is a seven times walking around Kaaba. The other is Saay which is a back and forth seven times between Safa and Marwa mountain. I was taking a class with Christian Linden who was teaching on land art at the time, so I wanted to reference these rituals through my practice. I also took a class with Sebastian Alvarez called Ambulation which was specifically about walking artists. I consider my walking as performative acts that there are no audiences to witness. Very recently I learned about the Situationists and derive, so I wanted to be innovative, to put together these concepts and decolonize art history.

Nanette: Decolonizing art history is an ambitious agenda, especially if you are doing it one step at a time. . . to clarify, are you referring to the white male domination of the canon and the art world in general?

Minoosh: For sure. I don’t necessarily shout it out loud. Even with the comedy. . . A lot of my work is about duality and contradiction between two things. So I’m criticizing the art world but at the same time I’m making art. When I was in Iran I was collaborating with Open5 Collective, a group who were making environmental art. The studio was outdoors. The works were ephemeral and not welcomed in gallery spaces because they were not selling, although they were photo documentation. So I think it is the way it is seen in art history. Each next group of artists comes through and wants to challenge and build upon previous artists.

Nanette: What does it mean to be an environmental artist today?

Minoosh: I think it’s difficult to be an environmental artist when sustainability matters for being an artist. For several years I intentionally utilized natural materials, recycled, and conceptually worked with the concept of natural elements—I avoided making objects. But I think environmental artists have to be activists, and I don’t consider myself an activist. I have been advocating environmental issues in my work even though not literally illustrating that.

Nanette: Yet there are strong connections between issues of colonization and environmental stewardship/equity so you actually are an activist. . .

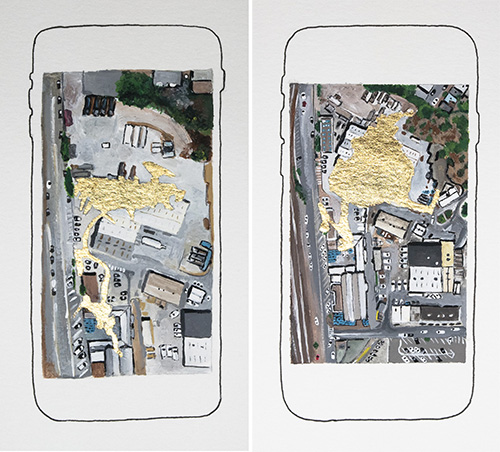

Minoosh: I’m not sure of that. I may go somewhere to better understand a border or a neighborhood but I don’t comment on that. I use those acts as a metaphor. But the way this started was in 2016 when the immigration policy in the United States was about to change. I decided to respond by claiming the land virtually. I start walking in different public places, especially in national parks. I claim ownership of the land that does not belong to me. It’s this idea of abstract absurd.

Nanette: But the act of doing it is an act of activism.

Minoosh: You call that activism?

Nanette: I do. I think that this is part of today. It’s very current. Women artists have been doing it for decades despite how they identify intersectionally. It’s in all of the identity politics of today, whether it is gender or racial, and race isn’t even a real thing, it’s something that we have created. People who are saying “I am here.” That is an act of activism. Just like making art about nature is saying, “Pay attention to this.”

Minoosh: Don’t you think that is your description?

Nanette: Yes.

Minoosh: The way I look at activism is when you go out and advocate for bigger issues and are not thinking about making art. Doing the activism for a result in society. Making yourself vulnerable for others. I call that activism rather than what I do in my studio or in my solo walks.

Nanette: In your artist’s statement: What do you mean by “the power of technology as a colonial structure.”

Minoosh: All of this time I’ve been using my smart phone, which I consider to be the most available technology, to document my routes and make maps of my walks. One has to have Internet access just to go around and track one’s path. The GPS tries to follow your route, but it’s not very accurate. It jumps. Even if you don’t have the Internet or your phone is dead, it still tracks your path and records. So now I have many images and recordings and maps of my walking in actual physical space, but I question, how much of this data is accurate. Who is deciding this is the border between America and Canada. These lines, these borders, are all given to us, how much is accurate from the technology. I’m trying to say that technology is so powerful that it can easily interpret and change reality. But also how long does it last? I have all of this data but who knows in ten years if it will be accurate. It’s like with wars and battles. . . how much of that history and memories and stories are coming back to us accurately. The power of technology is in the ways it can be easily changed, informed and interpreted because of limitations in its current accuracy. We can easily change things.

Nanette: One can easily colonize because of that? Because of the way that technology works, it can easily allow people who are in power to expand their boundaries?

Minoosh: I think it can. Who can just say No? It is so easy to see this in my normal, not very complicated app, that everyone has on their phone. I can change the accuracy of where I’ve been and I make that a record. And it is not accurate. It can be used for other purposes… If you look at the maps… What used to be Iran in the past? There is some battle and the borders change. In the past that happened through war and now it happens through technology. In my recent series Made Lands, I’m interested in using technology to re-form and re-imagine the memory from the physical land.

Nanette: You are talking about memory and how shallow human memory is and that technology is extending our memory. In some of our previous cultures if libraries got burnt we lost all of that information and history.

Minoosh: Yes. In my new work, memory is an important element. I take photos of my walks and through some glitch the images change. What I am trying to say with these distorted images is: what will be the memory of this space? The maps are documented with the recording of the walks, but the memory is through photographs.

Nanette: And our memories are not accurate.

Nanette: True. It will be interesting to see what our memories of this pandemic will be like. How many of us will remember about teaching in person. I found myself thinking it was easier to teach on zoom. . . How have we been changed? We are dependent on these technologies. I’m not saying bad or good, but noticing through my own life.

Whirligig: You often work with others. Tell us about a few of your favorite or most successful collaborations.

Nanette: You would think that collaboration has to continue for a long time, but that’s never the case for me. In my opinion, collaboration is successful when I learn something new from it and take it with me. Back in Iran, I collaborated with a group of Iranian artists Open5 Collective for six years. I had so many great times and memories working with them in Iran. I dream of those times now. Moving to the U.S. disconnected us. I believe it was the right time for me to start working independently and focus on my own projects rather than collaborative projects. When you work collectively, sometimes you get lost and can’t find your way.

I have collaborated with The Walk Discourse for two years, which was a monthly walk led by different artists in the Bay Area. I think it was very successful for me in terms of working with a non-Iranian collaborator and pushing the envelope. I’m a shy person but this activity helped me to grow personally. I learned a lot from Astrid Kaemmering about how to build a community. She helped me realize that I should believe in what I intuitively have started to create.

Another collaboration was a film project Golden which took over two and half years to finish. It was sometimes challenging and fun and my first time working with a poet. This collaboration came out of the Djerassi Residency in 2016 where I met Annie Albagli, Cintia Santana, and Carolina Chen.

Nanette: Is there a specific project which taught you something vital, something which transformed you or your practice?

Minoosh: Maybe I can say the first collaboration that I did in Iran with Open5 Collective was a seed for my long term practice. It helped me to make art collectively without description of roles and responsibilities. It was a huge provocative move for me. And The Walk Discourse helped me to connect with a new community and develop my walking project.

Nanette: Your work is highly conceptual. . . Currently you are making objects. What does the object do for you personally that is different from media-based and performative artworks?

Minoosh: Objects are more like something that you can sell, that you can participate in the show, because not every show wants conceptual art. They want to sell. One of the reasons I started making these objects was exactly that. Not everyone needs performance and depending on what you’re aiming for you can sell that object as something that is tangible that shows part of what you have been making. Your creative process becomes an object that people can see. But honestly, it was more of my struggle. How can I make performances as an object. The only thing that I could think of was documenting by video and photo. It was later I turned to sculpture.

Nanette: Do you like making the objects?

Minoosh: I started with craft as a hobby. When I started grad school at SFAI I wanted to challenge myself to be an artist but not make any objects. It was challenging to make art that is interesting and considered good art but not have an object, but it was very helpful and I am glad that I did that because it pushed me towards stronger conceptual work.

Nanette: Some of the photographs of your performance works are really quite exquisite and the videos hold up on their own as well.

Minoosh: But in the art world video is considered by its production and is endlessly reproducible. Whereas painting is considered differently. I’m also considering the challenge of making something that is not reproducible. So it is also playing with the idea of originality. It is more valuable when it is unique, it is only one.

Nanette: That’s part of the canon. If it’s unique it has more value.

With exhibitions like Hofreh at Peephole Cinema (SF), and Emotional Numbness the impact of war on the human psyche and ecosystems (U.S and Tehran) you are developing a reputation as a curator to watch. What is the role of exhibition curation in your practice?

Minoosh: One of the things about being an artist is that you have so little time. What I like about curation is that you create opportunities for other artists. There are some ideas I am very interested in working with and curation is a great way to talk about what interests you through other lenses. I think I use it as a type of messaging about things that I like to think about and talk about.

Nanette: In the last five years you have achieved a significant list of Bay Area artist residencies and a few across the states as well. Talk about your experiences as artist-in-residence and the role residencies play in your art practice.

Minoosh: It’s amazing. I am so lucky to be in this place even though so much happened at the same time. I haven’t always been getting the residencies. I have been an alternate and I always say Yes to things. The residencies that are not in the Bay Area have been more successful. When I am in the Bay Area I still have to work. But the ones that are so far away that I have to fly there, I just do art and no work. What I found about residencies is the time is very productive when I know it is one month and I will be in a place and I have to make something. Maybe having a deadline is helpful and not having distractions, and being focused. The distractions from the daily jobs or whatever you normally do is so different from being on a residency. The residencies I’ve had outside of the Bay Area have been so productive. At Ox-bow I made so much work. The ideas that come with that time. Also, you get to meet so many people. You get to meet a lot of curators and I have made some friends through residencies. Connection, community, networking.

Nanette: What and who inspires you to create?

Minoosh: I think I can get inspiration from anything. Everything makes me curious. Just thinking about the moment is fascinating. Inspirational? Love of looking at art. Nature. The sky. Sometimes crazy things like the colors of little leaves, anything that gets my attention at the moment. Also, the News. Especially, depending on the times, I listen to the news when I work. I get bombarded with all that’s happening. It’s the best way that I can be informed about what’s happening in the world. I don’t want to be isolated and stay in my cocoon. I want to grow and know what is going on in this country. I get inspiration from that because I try to respond and act. Not be passive in the world.

Nanette: Tell us about your educational background, how you came to be an artist and how you came to make your home in the Bay Area.

Minoosh: In high school in Iran we take an exam and apply to college. I was accepted for mathematics. I am a twin. My sister was accepted to art school and my parents wanted us to stay together. Move forward to the United States 20 plus years. I wanted to show my work. I was tired of so many things in Iran. The art world there is a very dirty scene. I got a show in Durango, Colorado. I hadn’t planned to come to the United States. But my friend said let’s go and we figured out the process to apply for a visa. I was surprised because no women my age get that visa. I remember I brought my portfolio to show at the embassy which was in Dubai because Iran doesn’t have an American embassy. So I had the show in Durango. I was supposed to go back to Iran after a month, but I found out about going to school. I applied and was accepted. Now I have been here for eleven years.

I ended up in the Bay Area because I have a relative here who I could stay with. Then I started school. It was very challenging because I had to figure everything out. My parents wanted me to go back. But I didn’t want to go back. First I went to community college which was very expensive for an international student. I finished there and I was about to leave when I got a scholarship to SFAI for graduate school. So it was a lot of time being in school.

Nanette: You went to community college here? Which one?

Minoosh: Berkeley. I highly recommend it. They have a really good multimedia program. I had the best teachers ever. The education is so different from in Iran. I had no idea what to expect because there is no one in my family or friends who knows how it works here. I am the first woman, and at the time the first person, in my family to have a higher education. It’s so hard being the first person and not knowing anything. . .

Nanette: Because you didn’t have that mentoring.

Minoosh: Exactly.

Nanette: Did coming to the U.S. change your art? Was your work conceptual in Iran?

Minoosh: I was doing photography. I wasn’t making commercial work. I was very interested in documentary photography. I was documenting a lot of ceremonies, rituals and traditions in Iran. That is where religion plays in my work. In Iran, the focus in Art History is on European and Western Art History. It’s not about Iranian artists. So I learned a bit about conceptual work there. There is not a lot of information or focus in the Iranian educational system about Iranian artists in Iran.

Nanette: So when you were in Iran did you know about Shirin Neshat?

Minoosh: I did know about her because she is very famous, but she is also from America and is considered an American artist.

Nanette: But wasn’t she born in Iran?

Minoosh: Yes, but she came here when she was 17. She is living in exile. I think she considers herself to be Iranian-American now. A lot of people come here because of persecution, their lives are threatened, or because they don’t like the Islamic Iranian Republic, or because they don’t want to wear the hijab. They can’t go back. They have to stay. I think that is part of her life.

Nanette: Are you allowed to tell me what you are working on, here at Recology?

Minoosh: I’m not sure what I’m working on. I have all of this architectural stuff and I’m trying to make spaces. When I started the residency here I was thinking about having a house, a home, and I picked these materials. Then pandemic happened. . . some of these items are about respiration and air. And now I’m thinking about why have I collected these specific materials. There is a lot happening in here. What gets your attention?

Whirligig Interview by Nanette Wylde.

Minoosh’s website: rahelehzomorodinia.com

All images used with permission. Copyright Minoosh Zomorodinia.