Photographer Marion Patterson has several new bodies of work coming out based on recent travels to Antarctica and the Galapagos. Patterson was mentored by Ansel Adams who became a lifelong friend. She also studied with Dorthea Lange, Pirkle Jones, Jerry Uelsmann, and Minor White. She studied philosophy at Stanford and received her Masters in Interdisciplinary Creative Arts from San Francisco State University. Patterson was faculty at DeAnza and Foothill College for 28 years. She currently makes her home in Anchor Bay, California.

Whirligig: How did you come to paint on your photographs.

Marion: I was a painter first. A watercolor painter. But from an early age it was always photography, and then I fell into the Ansel Adams circle.

When did I start painting again? Maybe when I saw Holly Roberts’ work. She paints thickly and saves only little bits of the photograph. Instead of that approach I wanted part of the photograph to be painted on. I love paint. When I got my Masters at San Francisco State I took a course in animation in which I had to draw on cels. It’s an incredibly complicated thing. I made a camel walking across the screen and all this stuff. It was two or three minutes of film. My instructor said, “Did it come out the way you wanted it to?” and I said, “Yes, and that’s the problem.” It didn’t give me any surprises. The thing with paint is that there is always a surprise. Even with drawing there is a little surprise depending on how you hold the pencil. That’s what I love about paint. It leads you. The camera leads you. The darkroom leads you.

Whirligig: When you are isolating a particular element in an image what are you thinking about?

Marion: It is a matter of how do we see? How do we perceive as we do? Why do we perceive what we do?

I sit in front of the image for a long time and I think what do I see in this flat image? Where is the feeling for me? Then there is that first tentative putting of paint on. With a glossy surface you can lift it right off which you can’t with the Hannemule paper. If I make more prints from Antarctica I want them done on glossy paper where I can move the paint around. On the Hannemule you put the paint on and it’s in. You can’t take it out. You’re stuck. I like to put on the paint, wipe it out and build up layers. Sometimes I make it drip. There are so many things we can do instead of punching apps. Excuse me, but I have this thing about obsessing with the latest apps. I love the fluidity of paint. All of the programs on computers just don’t have that.

Whirligig: When you are reflecting on the pictures from Antarctica where do you go? Is it reflections on your capturing time, or are you right back there, or is it something else?

Marion: A flow in between I’m sure. Or, not even. When I was working on the Antarctica images, and it took me months because the experience was so intense. I put together a little snapshot album of desktop prints. It was all down inside me and I couldn’t will it to come up. It had to come up in its own time.

I made eight different images which I call Cantus Antarcticas, Song of Antarctica. I got that out of my system and said to myself, I need to paint. Without the photographs, I still need to paint. I got a bunch of old matt board and some paper and I started doing these little paintings. I’m not taking these seriously. They are just play. I just needed to get it out of me. Everything started looming up. They are the last of the Andes.

Whirligig: They are very expressive.

Marion: There is an oriental quality. There is an incredible play of light and dark there, and not much in between except the skies were gray. Great skies. So then I decided I would just do line drawings. Then I decided to do diluted oil on top of the photographs.

I’m now mulling over what to do about the Galapagos. This [Antarctica] was my world: the light is so spiritual, the dark looming masses and glaciers, the ice and snow. I would say to people on the trip, “Can you believe what we are looking at?” and everyone said, “There are no words. No words for this.”

Galapagos is very literal. There are the iguanas, the seals, the blue footed boobies. Now I’m at the point where it has been a couple of months. What do I do? It is all color. I have some black and white, infrared and digital. Nothing moves me in all of this.

I have this funny thing that happens when I start really seeing. My fingers start to twitch.

Whirligig: In terms of your life can you look at decades like the 50’s, the 60’s, the 70’s and the 80’s and describe them?

Marion: I’ve been trying to because people have been asking me to write my memoirs. That is where the computer is great. I started writing from 1933–1958. I got myself through Stanford, probably into my second year of art school. That’s when all sorts of things started happening. Art school was a great liberation. Stanford gave me intellectual discipline. But it was crushing. My home life was crushing. Art school was Wheeeeww. And Ansel was there in my class one day. My instructor said, “Ansel, this is Marion Patterson.” Ansel jumped up and said, “You do beautiful work Marion.” I said, “No I don’t.”

Whirligig: How old where you then?

Marion: Twenty-three maybe

Whirligig: It was graduate school?

Marion: Yes, but there were no degrees in photography in those days. My teachers were Dorthea Lange, Minor White, Ansel, and Pirkle Jones, who as a teacher was very encouraging but he wasn’t a powerful influence. The painters were blasting away with abstract expressionism and figurative paintings. It was 1956 – 1958. The beat poets would come in and read. Anna Halprin would come in and dance. It was just a gutsy, gutsy place. I think we were all anarchists, breaking everything loose. The dedication was totally to art, not to ego, not to money, not to materialism, not to getting exhibits. Because there weren’t any in photography, to speak of. It was about exploring the medium, certainly in photography. Abstract expressionism was being done and there was the figurative school in painting. So you get this layering of paint and this richness of paint. Nathan Olivera. Diebenkorn was around. We would go to City Lights in North Beach and hear Ginsberg.

I went to the Guggenheim in New York a couple of years ago. They had an exhibition on the influence of Asian philosophy in American art. I looked around and knew the work. I was there. This was MY world. Â I had come from the philosophy department at Stanford, which was focused on logical positivism and the beginnings of the computer era, to the exuberance of letting the emotions blast out .

I used up all of the photography classes at the California School of Fine Arts in two years. Then I went to Yosemite. I had already bought my land. Built my cabin. I went up there and got fired from the concessioners for mouthing off. Got hired immediately by the Adamses.

I was so screwed up, suicidal, you name it. Ansel said to me, “You are not a misfit. You are an artist. All these things that people are criticizing in you, it is because you are an artist.” I said, “But there is no place for a woman.” He said, “We need women in photography.” It was three years of incredible support. I questioned everything I believed in and did a total revision of who I was. And then it was time to leave. So I went off to Mexico. Ran out of money. Came back.

Whirligig: How old were you at that time?

Marion: I was about twenty-eight.

Whirligig: Were you photographing all this time?

Marion: Yes. Then I went to work for Sunset Magazine as the grunt. I learned a lot about studio photography, commercial photography, how a magazine is put together. I ended up roughing out the layouts, designing the photographs, and getting paid slave wages, but it was a great learning experience.

I saved up enough and I inherited about nineteen hundred dollars, so I got in my little VW and drove down to Oaxaca. I knew I wanted to live in Oaxaca. While I was working at Sunset I had been making prints, using their darkroom on weekends, so in the meantime I had a solo exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art. I came back from Mexico, saw my photographs on the wall and said, “They belong. I don’t have to worry about that again.” I went back down to Mexico and then I had an exhibition at the old Oakland Museum of the Oaxaca photographs. Then I was scrounging it out, hiking the John Muir trail by myself, going off and doing crazy things. It was the 60s and 70s and it was so vibrant. I look at the art scene today and see that it just doesn’t have the guts that we had back then. And it is rigid. I want to see splashes of paint and instead it’s pixels.

I started teaching part time at DeAnza College. I didn’t have a Masters yet. Then I hurt my neck and we thought it was going to be gradual paralysis. I needed to get a master’s degree in order to teach, so I went to the University of Florida to study with Jerry Uelsmann. I could not stand Florida and that whole scene. San Francisco State was just starting an Interdisciplinary Creative Arts major. Ralph Putzker was there, and he got me into that program. I had a blast. I made a little movie that stars Imogen Cunningham. I did graphics. I was in the graduate seminar in photography. I took a course in Myth and Ritual that just sent me way off in Jungian psychology. It was a lively place. Then I taught part time and was doing my own artwork.

When the full-time position came up at Foothill I had been teaching part time for eighteen years, with no benefits of course. I said well it’s close to Yosemite. It’s close to the city. I knew I could shape up the program, so I took the full time job for the benefits and the chance to create what seemed to me to be a meaningful, realistic program. I retired one year early of retirement. So I don’t have much money, but I’ve been to Alaska. I’ve been to Antarctica and the Galapagos. I’ve climbed Kilimanjaro and a little way up Mt. Everest. I’ve seen wild animals in Africa. I want to understand the world.

I remember my dear old doctor saying, “You quit Sunset Magazine. That was such a good job.” I said, “Yes.” He said, “People will think you are unstable.” I said, “I am unstable. I don’t want to be stable.” It’s like a doctor up here said, “You’re not going to take Lipitor and all these diabetic medicines?” I said, “I don’t think I’m diabetic for one thing.” She said, “Don’t you want to live another thirty years?” “And be a hundred and three? No way!” I don’t take prescription meds. I walk. I listen to music. I sit on my deck. I play with my cats. It’s a good life here but it’s not enough now.

Whirligig: How long have you been in Anchor Bay?

Marion: You know I lost everything in the fire in Yosemite (1990). I rebuilt, but the spirit was gone. I bought this [home] Winter Solstice 1990. Moved up thirteen years ago full time. Put in some improvements. Put in the whole garden. But there is a lack of stimulation up here. I had all those years of work which had to come out. All those negatives to print and drawings to do. But now that is done and I question if I have the guts to start a whole new life. If I don’t have the guts, forget it. It will be scary. I look around here and 20 years ago I had nothing. I was wiped out. Now I have too much. I love my books. I love folk art. But that’s on the material level.

What I didn’t talk about yet was my being a philosophy major at Stanford and not finding the answers to the BIG questions. I found no answers in Christianity. There was so much more, but where was it? Then listening to KPFA and Alan Watts introduced me to Tibetan Buddhism. So I found my way into a sangha and there I was, sitting there with these high Lamas. The highest. Just sitting on the sofa asking the meaning of things, of life itself. I took a one week workshop with Chogyam Rinpoche in Colorado, and with lots of other teachers and teachings in Nepal. Of course (at the time) Tibet was closed off. I’ve taken two trips to Tibet.

What I didn’t talk about yet was my being a philosophy major at Stanford and not finding the answers to the BIG questions. I found no answers in Christianity. There was so much more, but where was it? Then listening to KPFA and Alan Watts introduced me to Tibetan Buddhism. So I found my way into a sangha and there I was, sitting there with these high Lamas. The highest. Just sitting on the sofa asking the meaning of things, of life itself. I took a one week workshop with Chogyam Rinpoche in Colorado, and with lots of other teachers and teachings in Nepal. Of course (at the time) Tibet was closed off. I’ve taken two trips to Tibet.

I love the oceans. I love the mountains. I love the deserts. There is so much to see.

Whirligig: It seems that being in natural environments as opposed to built environments is important to you?

Marion: Yes. My students use to ask, “When were you the happiest?” And I’d say, “When I had a pack on my back hiking in the Sierra, the Muir trail, any trail. I need space. I need nature. I tried living in San Francisco and I lasted one week. Too much noise. If I move to Carmel it would have to be out in the Valley. Many of my friends are there. There is the Ansel tradition. There is the whole Big Sur tradition. There is a lot of experimentation going on.

We have to discuss. We have to explore rather than saying, “This is true.” The on/off way that it is now.

People say, “Why will you move?” I respond, “There is a door opening. That’s all that I know.” I don’t know what’s out there. It may be a total debacle, but I’ve been through that one before. My closest friends have all died. My home in Yosemite is gone. What’s left? I’ve walked away from Buddhism because the teachings were all looking backwards. I find the experiments in the sciences, especially in physics, are the real philosophy now. The old religions and dogmas and so forth, they’re past. There is excitement about being around Silicon Valley because there is a daring there. I couldn’t go back and live there now. I don’t know what’s going to happen. I’m not in charge. Something has used my life, and I can’t complain, but  it would be nice to have a little more money. . .

Whirligig: Why are you fascinated with the sciences right now?

Marion: Because they are opening up worlds. There are so many possibilities. You look outside beyond the clouds and see that this isn’t all there is. The possibilities are beyond imagining. You can read something about how birds flap their wings. I’m fascinated with that. I’m fascinated with astronomy and especially physics. I’m fascinated with the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS), who also deal with parapsychology. There is so much that I can never understand in this lifetime. Being a Buddhist I do hope I have another go around or thousands of them because I’d love to see how consciousness is evolving. That is part of what’s going on in my work—how perception is evolving. Or our perceptions of our perceptions.

I read New York Science Times and other things that I can get. I can’t understand it really, but I play with it and I play with the possibilities. Consciousness is evolving so fast now with the influx of Eastern religions and what we are learning about psychology. Just the information sharing, which is overload. I don’t do Facebook because I don’t want to be overloaded with what all these people think about things. But technology is allowing the expansion. I just find the world incredibly fascinating. Even how a cat walks is fascinating to me. I sit on my deck and say to myself, “This is perfection.”

I’ve studied Buddhism for 55 years and have taken a lot of teaching, but I have decided that I want LIFE. I don’t want relief from pain. I think pain is important. I think blundering is important. The whole soup–you should plunge into it. The night before I left for my first trip to Greece, I met with my Buddhist lay teacher and said, “You know, I’m finished with all these texts. All you are doing is looking back. I want to look forward. I want life itself. I’m ditching Buddhism.” Then I went off to Greece which was an incredible trip where so much of life has come together. You can walk where Agamemnon walked. That whole richness that you take in through your pores, not through your brain. I said to Ansel’s daughter and her husband, “I’m liberated from liberation. I am free.” I came back and met with a group and the Buddhist teacher and said, “I hate to say so but all of this is over for me. I feel liberated from liberation.” She said, “You are liberated!” I thought, Yes, but I think there is a bit more to it than that. But I am free of it. Free of all the dogma. Free of all the book learning. The wisdom of the great thinkers is to be read, and then forget what you read. I think these cats have got it right. They eat and they sleep and they are dependent.

So many of my friends are dead. I’ve thought, well, what else is there? The next adventure. I’m close to dying and I’ve been there on the other side with an out of body experience.

Whirligig: Would you regard your studio practice of being a photographer all these years as part of a mindfulness practice?

Marion: Absolutely. Why did I choose photography, writing with light. I’ve always been drawn to light. The first word I spoke was sunshine. I  used to be called Little Sunshine. Strangers  have called me sunshine. Wynn Bullock said, “Light is the ultimate truth.” It is all about light. So photography was natural.

Whirligig: How did you get your first camera?

Marion: It was WW2. I was eight or nine years old. Merchants would put up items and you could bid your savings stamps or savings bonds on these things. There was a camera and I really want that camera. I had saved up 35 cents. We were very poor so 35 cents was a lot of money to me. I bid my 35 cents on the camera and the bidding went out of sight. So I told my brother to take me home. We were walking out of the crowd when this man appeared and put the camera in my hand. He said, “I know you want this” and he disappeared. Who was he? He gave me my first camera. With all the teaching, I think I’ve repaid him his gift. Our lives go the way they are suppose to go even with rough times.

Whirligig: Where did you grow up at?

Marion: Burlingame. I was born in San Francisco.

Whirligig: Can you talk about teaching.

Marion: I loved teaching up until the last couple of years, when the students started wanting to know how to get an A or how to make money. For me the camera can be a passage to what’s out there and what’s inside us. With a camera, we can become one with what we are looking at, and through that, we can access our inner landscape. When I look at someone’s photograph, I want to know what the photographer is trying to say to me. I ask the person, “What do you want me to feel? What are you feeling?” Then I hear, “Feel? Look at the histogram.” And I say, “Not enough.” We are in this gee whiz stage of digital photography. I think the need for something more will rise and begin to achieve a balance. I hope so.

Whirligig: I think we’ve been in a gee whiz stage since the Industrial Revolution.

Marion: That was the big change. Now we have these endless wars. There is now a new fad which is the coming of the Maitraya Buddha. The Maitraya is supposed to be the next incarnation who will bring world peace. There is even some guy who thinks he is the Maitraya. Well, he has a big job ahead of him.

Whirligig: You were a functioning adult at the advent of television. You saw that revolution. You saw the advent of the personal computer in 1985, and now we are here.

Marion: With these little machines. You’ve used that one word, personal, which says it all. Everything is about self. Facebook is about self. My self. My cell phone. My. My. My. It’s isolation. We are self isolating because of our little machines. But it is a little machine that brought us together today. It’s a tool. Technology is just a tool. It is not the answer. I don’t know where the new wisdom is coming from. I think it is out there. Groups like IONS are getting into alternative medicine, parapsychology, the real sciences. I don’t know what is going to bring it all together. In Antarctica you watch the ice fields crumbling. On the next trip I’d like to go to the Arctic and see the Polar Bears before they are gone. I don’t know if we can save this planet.

Years and years ago I said to my philosophy professor, who was a great love of my life (I kept up with him until his death), “I think humans will have to go if the planet is to be saved.” He was horrified.

I don’t know. Do I hope at all? I’m going to wait and see what happens. I’m very concerned about the planet and what is happening to humankind. This terrible disparity. One in six people in the US are starving. There are some people who are so affluent, yet it is all crumbling. I think the Dalai Lama is in despair. Using non-violence and not saving Tibet. There is a certain advantage to being as old as I am. I won’t have to live another 30 years and watch this great shift. I love China, but they are ruthless.

Whirligig: I think the planet will eventually shake us off like a bad case of fleas. Humans are smart and cunning but the planet is powerful.

Marion: Look at this climate change.

Whirligig: What are the most special places you have visited.

Marion: Yosemite will always be my home. It is my heart. The trip to Antarctica—it was a great group of people, a great ship, a great itinerary, but it is that untouched space. It is raw. It is primal. You can’t live there. Thank heavens. There are various research stations that have been abandoned. Antarctica is spiritually primal. Galapagos is primal but it is in a physical way, going back millennia with all these strange creatures.

Being in the Himalayas in the moonlight. Everest is not a beautiful mountain. But they call it the Great Mother. I thought it was the ultimate until I saw Antarctica. I thought nothing could compare with photographing Mt. Everest, Tibet, in the moonlight with the stars moving across the sky. But Antarctica is beyond that because there is no trace of mankind there. The penguins’ only predators are the seals. It is shear beauty. It’s austere. It’s foreboding. There is a humor to the penguins. There is an incredible beauty to how the albatross fly. It is pure. Years ago I had a dream of being out in space, visiting planets and stars. I came to a planet, an ice body. It was all white and so beautiful. I can still see it in my head.

When I had my out of body experience in the Sierra when my body pooped out and I suddenly realized I wasn’t going to make it, I realized I was out there way up above. I could see some guy running and telling me I was going to be rescued by helicopter and I had to come back. I didn’t want to come back. There was a dark tunnel, maybe the chakras. I was trying to realign with my body but I was thinking, “Just let me go back out there.” I was free, and everything was so beautiful. That was way before anyone talked or wrote about out of body experiences.

Whirligig: So what happened?

Marion: I was hiking and met this young guy on the trail. The first night I felt a tearing sensation in my side. I was going out with Brett Weston at the time and the ranger was a friend of Brett’s. So I said I had a sore knee. I didn’t want to say I had gut trouble. So I said, “What’s the easiest way out of here?” It turned out that completing the trip would have been the sensible thing to do so I kept on hiking. I got weaker and weaker and couldn’t carry my pack. I got to Evolution Lake and just collapsed. The young guy ran four miles back to the ranger station. The ranger commandeered a horse and called in a helicopter the next morning, so they hauled me out. It was probably a ruptured ovarian cyst.

But I had that [out of body] experience. Same with Carl Jung. He didn’t want to come back. There is so much more.

Whirligig: Are there other places?

Marion: The opera, going to Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival with a handsome man I met on a camel in China. When I was at Stanford and thereafter I ushered at the opera house just to be with music. I have no talent but I love it, maybe more than anything. So I’ve gone to musical performances here and there.

I love the Amazon River. Again it is space untouched. Wilderness. Flying over Denali after a new snow. That mountain is so beautiful. Of course Everest and Tibet. When I came back from my first trip to Tibet, within hours I was sitting down with a very high Lama in Palo Alto. I said, “What am I doing here. Tibet is home.” I knew Tibet backwards and forwards. I could walk around Lhasa before the Chinese trashed it. It was home. So what am I doing in this body, in this house in Palo Alto?” He said, “You have work to do. Now get to work.” It’s a long process. My consciousness has evolved over perhaps millennia  and I hope it will keep on. I think I’ve always been in touch with the non-physical that I am. That’s why when you are out photographing you get rid of yourself. You are no longer stuck with yourself. You are seeing beyond. When you sit and play with your art, that something happens.

Whirligig: Do you still have a darkroom?

Marion: Yes. Out in the garage. One of Ansel’s assistants built my darkroom. He was my height so he built my ideal darkroom. It is my dream darkroom.

Whirligig: Do you have some favorite anecdotes from your time with Ansel?

Marion: He was the most brilliant, as far as IQ, talented, generous, wise, warm, funny person that I ever met. I loved to hear him play the piano. He could have been a first rate concert pianist. I was down there the day he died and Vladimir Ashkenazy, the pianist, was doing a recital. Ashkenazy said, “I would do anything for this man.”

I had dreamt the night before that it was going to be that day. I adored Ansel because he was music. He could write beautifully. He was dominated by light. Which I am. He wasn’t my ideal man. I think Peter was. But he was so much more than a father figure. He was a friend. He was a colleague. The works.

His wife, Virginia, made it all possible. After Ansel died all the friends who always came for dinner and drinks just disappeared. Virginia was the one that made sure all the cocktails and food were there. And all the hanger-ons disappeared. I was disgusted. Ansel and I had some deep, deep talks, and Virginia was the mother I always wished I had had, because my mother didn’t have a clue who I was. She tried to make me into a nice Stanford girl who married a nice Stanford boy and made lots and lots of money, and had two kids. That wasn’t me at all so there was a terrible disconnect between who I was suppose to be and who I really was. Virginia nurtured who I was. I always say they saved my life.

As far as anecdotes. . . I had just gotten a tape recorder and I said to Ansel, “I’m going to ask you some questions and I want you to answer in dog barks.” Because he could imitate anything. So I said, “Mr. Adams. What do you think of the state of the environment under James Watts, Secretary of the Interior?” And he would howl. Somebody has got to say that this was a down to earth, funny human being.

Every time I had a question he would answer it but then take it a lot farther. I learned the zone system right from the horse’s mouth, and I still use it.

Lange gave me an awareness of the human condition. Minor White opened up the whole spiritual end. Here’s an anecdote. I was staying with Ansel. Virginia was away somewhere. A friend of mine, Helen Wallis and I were in the house with Minor White and Ansel. Minor White said, “Tell me Marion. What is your astrological chart like?” I said, “I’m a triple Taurus with three in Virgo and only one planet is in opposition.” “Oh yes,” says Minor, “Oh yes. That explains why you’re drawn to nature” and blah blah blah. Ansel was frowning. Then he said, “Marion what film developer are you using? what paper?” So I said, “FG7.” After dinner, Minor pulls me over and says, “You don’t believe that stuff Ansel is talking about is important, do you?” and I said, “Well, yeah.” Ansel pulls me over, “You don’t believe that baloney about astrology do you?” “Well, yeah”

So in spite of all my turmoil, whoever is in charge has taken me on an amazing journey—internal and external.

Whirligig: Do you think you have normal turmoil or has your turmoil been extraordinary?

Marion: I think I was acutely sensitve. My mother was forty-four when I was born so I was either dingy or bright, or a mixture. My father died when I was four. I adored my father. My mother was a disciplinarian. She was from New England. There was one way to do things and if I didn’t do exactly what she said, I had to drop my pants, bend over her knees, and get a serious spanking. I got a lot of physical punishment and it was a humiliation. At age four when my father died I just apparently quit eating. They pumped me up with tonic, and I am still going.

I’ve always known things which you can’t explain rationally. So I tried to please my mother, otherwise I’d be punished. I learned not to be creative and not to listen to my intuition. My brother became difficult. He physically beat me, and I became afraid of him, although we had good times, too. With no father and this rigid mother where the word sex was not mentioned at all . . . He didn’t have close friends with whom he could talk about all this . I had Ansel, Virginia, and K. Lee Manuel. Over the years I’ve worked out so much fear, insecurity, and alienation, but much is still there.

When I said I’m liberated from liberation it was like ditching all that karma. I’m free.

I was so driven all my life. But my artwork is not about making money. I’m dumb. I cannot self promote. Money doesn’t matter. I have enough. Fame. I could have been famous but Ansel said, “Don’t do what I’ve done.” He said, “At one point I wish I could have been more like Edward Weston.” Weston basically lived in poverty. His whole life was focused on his photographs. Ansel was just too brillant to be stuck in one form or another. He was so complex.

Whirligig: Did he find celebrity to be weighting?

Marion: Yes. Definitely. He said, “Sometimes I don’t know who I am anymore. There is this persona out there of who I am but where am I? Please don’t do what I did.” Â Yet he loved the fame, and he deserved it. He gave all the technical expertise, such as the Zone System, for all photographers to use. He would be appalled at the price of his photographs now.

Whirligig: Or the hoopla over the negatives found in Fresno.

Marion: Which are so clearly not Ansel’s. Ansel would never have those people down in there. The one that they show a lot which is the Jeffrey Pine on Sentinal Dome, has a wonderful shape in the tree. The other guy, the psuedo Ansel just photographs it. Ansel photographed it with each shape relating to the other, the tree to the rocks below to the clouds. Anne Helms, Ansel’s daughter, said, “I feel sorry for the guy. He thought he had millions of dollars.” But we now know that somebody’s uncle took them. Some gallery owner and some lawyer thought they could make money off of this poor custodian from Fresno.

Whirligig: You mentioned you had an affair with Brett Weston. Do you want to talk about that?

Marion: (giggles) I always call it my obligatory affair with Brett Weston. All the young women photographers, and there weren’t that many of them back then, ended up having an affair with Brett. It was just part of. . .

Ansel said, “He’s not a nice person, Marion.” “Yeah but. . .”

He was glamorous, but he was cold. He treated women like they were just good for a f___ and a breakfast or something. There was a great glamour to it. I went to Baja California with him and another couple and that was the end of that affair. He was very patronizing towards women. They were just to be used. Same with Edward Weston. I was very close to Charis Weston, Edward’s second wife, who did much of his writing for him, ghost writing. I had her come up to Foothill where I was going to show a couple of Edward Weston films and she was going to speak. I plopped a bottle of wine down, and I don’t know how I ever threaded that projector. We were absolutely crocked. She said, “What do you think Brett’s IQ is?” and I said, “Eewww. I think maybe 90.” She said, “You are so generous.” He was not very bright.

Weston taught the boys to distrust women. Use women for sex. To drive their cars and carry the camera gear at times. No respect for women.

Whirligig: Maybe that’s why Sherrie Levine chose his work to copy when making her statement about celebrity being a white male photographer.

Marion: It’s still that way. It took Imogen Cunningham to age 84 before she got recognition, and Ruth Bernhard was 90. I think my legacy is through teaching. I owe that to Ansel and Virginia.

Whirligig: What would be your advice to young people wanting to pursue a life of art and creativity?

Marion: Stay out of school.

Whirligig: Do you think school wrecks them?

Marion: I think it can. Good teachers see the student and do little nudgings. They see the passion and the excitement, and let them find their own way. And they let them try each tangent. If it’s a dead end, fine. Try the next tangent. That’s where our community colleges are so valuable. If you are going for a degree you have to please your teacher. I got two Cs in art at Stanford because I challenged my instructor. The next quarter I kissied up to him and I got an A. It made me so disgusted that the next quarter I went my own way and got a C. But that’s a bad teacher and we’ve all had them.

Whirligig: In 1992, to initiate discussion among colleagues you passed out an article called “No more PoMo” What was that about?

Marion: I don’t remember that, but I remember taking on the art historians by saying, “I find Post Modernism boring.” What I was reacting against was a certain glibness, propagandizing, over intellectualizing about Post Modernism at that time. It was didactic. I was coming out of that free wheeling, let it all hang out, 50s and 60s, abstract expressionism. I heard John Baldessari lecture and I thought, “Spare me. What are you saying!” Peter Galassi out of MOMA NY, too. Afterwards I said to several people, “What did he say?” Nobody could answer. To me it was like there was a sterility to Post Modernism. I was almost comparing it to Russian poster art with the Bolsheviks when there was that postery, didactic simplicity. That’s what I was reacting against.

I happen to love beauty along with expression from the heart which is what art is about. To see somebody photograph Edward Weston’s photographs and put that on the wall was to me “So what? Where’s your heart?” I wasn’t finding the heart. Much of the same problem now is with the excitement over art made on the computer. There was a recent cover of the New Yorker which was obviously made on the computer and I was asking myself, “Why do I find this lacking? What frustrates me?” Because anytime something frustrates me there is a door opening. There was nothing tactile about it. I looked inside and it’s a David Hockney. My hero. But that is Hockney. He is always experimenting. He is always pushing it. He plays with art. So along came another cover and I looked at it and there is a complexity in the colors. I looked inside and it’s a Thiebaud. I put the two together and I am drawn to the Thiebaud.

Whirligig: But Thiebaud would never have faxed his drawings to his gallery in the 1990’s.

Marion: RIght, and I thought that was a kick. I love Hockney’s whimsy. I loved it when Hockney went back to drawing because he is a wonderful wonderful draftsman, expressive. But he got swept up in the fads like when he thought he discovered the camera obscura was used by Vermeer. We’ve known that for ages Hockney, come on.

Do you know this book Infinite City by Rebecca Solnit? I loved her writing because she is an environmentalist. She got the idea of doing San Francisco via maps. She calls them maps and atlases. Here is one: Where the Poisons Are. Where the Foodie Stuff Is. She is really getting San Francisco and the San Francisco style.

Whirligig: There is something very smart about this book, about honing in and researching the wonder and curiosity. All those things which inspire us to get excited.

Marion: Yes. But what I’m really excited about is this image of a bird in flight in the science section of the New York times.

Whirligig: And that goes back to Muybridge.

Marion: Yes.

Whirligig: Is there anything else you want to say?

Marion: Have confidence in your path. You don’t know where you are going but you are being taken somewhere. Keep your heart open no matter how much pain comes in because pain is a great teacher. I love Joseph Campbell. I took a 10 day workshop from Joe before he became famous. He said, “It doesn’t matter if you win or lose. Why not win.” That just turned me around.

Whirligig: Why?

Marion: Because I was brought up not to be smart because the boys won’t like you if you are smart. All these doors are shut because you are a woman. Defer to men. If you win you are going to be shot down. So “if it doesn’t matter if you win or lose why not win” was like Oh! you just gave me the freedom to achieve and to be me. Not what mother wants. I have followed my bliss.

Play. Laugh. Dance. Sing. Delight in everything. It’s all a dance. And read T.S. Elliot’s Four Quartets. It’s all in the Four Quartets.

One time when I was in despair because nobody was buying my work and I was broke, I phoned Minor White. He said, “What’s wrong?” I said, “I’m tired of doing work that nobody looks at and nobody wants. I just want to quit all this.” He said, “If one person is inspired by seeing something you have done you must keep working. Now forget about yourself. Get to work. Take chances.”

Whirligig interview by Kent Manske and Nanette Wylde.

You can see more of Marion’s artwork in this monograph:

Grains of Sand: Photographs by Marion Patterson, Stanford University Press, 2002.

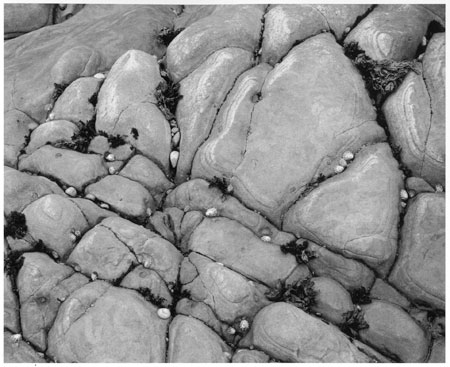

Images from the top: Antarctica; Antarctica Warming; Antarctica; Filaree; Grasses; Manchester Beach, Mendocino; Weston Beach, Pt. Lobos. Courtesy of and copyright Marion Patterson.