Meet Cynthia Sears, Champion of the Arts

Cynthia Sears is a creativity explorer and the founder of the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art (BIMA) on Bainbridge Island in Washington State. She is known for her extensive support of artists, writers and cultural entities. Her collections include paintings and sculptures; antique and finely bound books; and some 1800 artist’s books, which comprise the Cynthia Sears Artist’s Books Collection at BIMA.

A pioneer in cultural support, Sears has collected and donated numerous works of regional artists to BIMA, creating a rich legacy of Pacific Northwest artistic production. Her wide ranging appreciation of the arts is demonstrated in BIMA’s community-centered mission and diverse programming which includes musical and theatrical performance; hands on educational activities; lectures, tours, and a wide array of community outreach events including an online series Artist’s Books Unshelved. This year BIMA is launching four generous biennial awards to support both regional artists and an artist making books. These BRAVA Awards (BIMA Recognizes Achievement in the Visual Arts) are in celebration of the tenth anniversary of BIMA in 2023, and a further expression of Sears’ belief in the value of the arts to human existence.

We conversed via zoom over a span of four months, discussing a range of subjects which touch on aspects of Cynthia’s life and thinking, including her work in radio and film, social and environmental issues, collecting and philanthropy, education, and the arts.

Nanette: What is your background: growing up, education, early careers?

Cynthia: I spent my childhood in Beverly Hills. I went to public school through eighth grade and then to a girls’ boarding school in Virginia, Chatham Hall. I was actually relieved that I wasn’t going to Beverly High because the girls that I knew in 7th and 8th grade who were going there were so much more sophisticated than I was. They were very concerned with boyfriends and convertibles and cashmere sweaters. . . they were already like late teenagers. I wasn’t ready for any of that. The idea of going off to a place where you had lessons in the morning and then rode horses in the afternoon was heaven. My older sister went to Chatham first. I couldn’t wait to go because I met many of her friends, whom she would bring home during vacations. They were great, interesting girls, so I couldn’t wait to go. Going to that boarding school was one of the great experiences of my life.

Then, I went to college at Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania, also a small institution. The entire student body was only 750 girls. It was out in the country and beautiful. I just loved it. It looked like a medieval fortress—towering gray stone buildings which were built out of mica schist which catches the light so that it sparkles in the sun (I learned in my geography class).

I studied English Literature and Latin. I was sure I was going to be a writer. Well, that didn’t happen, but I was convinced of it when I was in college. I had a wonderful experience with terrific people.

Nanette: What happened after college?

Cynthia: After college I got a wonderful job teaching in the Bronx. I was a teacher at the Hoffman School. It was a school for kids who didn’t exactly fit other places, either because the child was super intelligent and could get bored in a regular classroom, or kids who had physical or mental challenges. They were all mixed together in the classes and it really worked. It was extraordinary.

I was hired as a Latin teacher. I taught Latin to second through sixth grades. We made Latin books and grammar books. They would say things like, “If the verb goes at the very end, how do you know who is doing what to whom? Maybe you make sounds so that you know this is the person who is doing the throwing and this is the thing being thrown.” They basically invented the accusative case.

Nanette: Latin isn’t really taught much anymore. People who know Latin know the meanings of almost all the words in Western languages.

Cynthia: Yes, and it’s oh so much fun. At the Hoffman School it had a secondary benefit. Many of the kids who were challenged for one reason or another, had brothers and sister at home going to regular schools. When the children would go home and say that they had learned Latin and could now read Latin, it was a big deal because their siblings weren’t going to get Latin until high school. That turned out to be an important aspect of their success.

I taught at the Hoffman School for three years and then I got married and went back to California and started on a different path.

Nanette: Did you get married to a California boy?

Cynthia: Yes. Both of David’s parents taught at Stanford and he went to Stanford as an undergraduate. I met him when I was visiting my sister who was attending Stanford as well. So we met when I was in college and married years later.

David [David Sears, a professor of psychology] got a position in the Psych Department at UCLA and we ended up living about two miles from where I was born. The weather and outdoor life make it a nice, easy place to raise children.

Nanette: You had a radio show “Writers and Writing” in Los Angeles. Will you share a few memorable stories from that experience.

Cynthia: I had been listening to KPFK in Los Angeles [a station in the Pacifica network of independent media]. I went to the station for one of their fundraising benefits and met some people. They asked what I was interested in and I said writing. They said, “Do you want to invite a writer over and interview him on the radio?”

I had recently met this young Canadian poet, Arthur Lane, who went on to become a distinguished professor, but did not publish much poetry. I thought it sounded like fun and Arthur was a good friend so I thought: How scary can it be? Well, It turns out I have acute mic fright. I was sitting in the broadcast room with a microphone in front of me and I was virtually in tears. Arthur looked at me and said, “I bet you’re wondering where I get my ideas, and I bet you’d like to ask me. . .” I didn’t have to say a thing. He interviewed himself. That was so easy. One thing I am really grateful to Arthur for is that he introduced me to Billy Collins, who was one of his best friends from grad school. They were having a poetry correspondence. Billy Collins has become a really close friend.

For another fundraiser I brought my older daughter, Juliet, when she was in second grade because she was a really good reader. She read Edward Gorey’s The Gashlycrumb Tinies on the air. The verses are so hilarious, especially when read by a seven year old.

By 1969 I was doing a weekly radio show. That turned out to be the most fun, apart from the scary part of dealing with a mic. I could call up any of my heroes who were writers and say “I have a radio program and I would like to interview you on tape.” And they would say, “Sure.” It was magical.

Nanette: It wasn’t a live show?

Cynthia: I interviewed on tape. I only did two live shows with guests that were self starters and happy to talk about themselves. All of the writers were so amazing in person—they were open and generous and funny. The fact that I was so visibly nervous must have been reassuring to them. There are times when the person in control isn’t actually in control and it turns out best.

Nanette: Were you writing at that time yourself?

Cynthia: No, I was writing just the intros and outros for the program.

Nanette: How long did you have the radio show?

Cynthia: Once a week for seven or eight years. I was able to spend a day with Isaac Bashevis Singer, who had just won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and another with John Cheever and John Irving. I spent weeks with Henry Miller because he became a really good friend. He lived nearby in Pacific Palisades. I had become an experienced tape editor because I had all these quavery introductions that sounded like I was on my last legs—I was so trembly in my voice, but with a razor blade and editing tape I could make myself sound brave and confident and literate. Henry had a disconcerting speech habit while he was thinking of the next thing to say: mmmm mmmmm mmmmm. I was able to edit that out and he said I made him sound like Alan Watts. He was so happy. When Henry Miller turned 80, Lawrence Durrell flew in from France and we had parties to celebrate Henry.

I interviewed N. Scott Momaday just after he had won the Pulitzer Prize for House Made of Dawn. I absolutely adored him. I had written a paper on his work while in college. He had the most amazing voice. As I recall he had been trained to be a preacher. . . When I went to interview him he was living outside of Santa Barbara. He talked about the myths and legends of the Kiowa people and then abruptly he had to excuse himself to go to his Gourmet Cooking Club meeting. He did a painting for me of a wolf and an eagle that I still have and treasure.

Nanette: You also worked in the film industry as writer and producer, mostly with documentaries. Your 1978 film, Battered, was strikingly innovative for it’s time—the subject of domestic violence and encompassing realities, the use of a narrative weave to follow multiple characters’ paths, the subtleties of showing rather than telling the individual stories and related issues, the inclusion of Black characters on socially equal footing with white, the absence of sensation and definitive final resolutions, and the fact of being a female writer and producer in a male dominated industry. What can you tell us about this experience—your motivations, challenges, joys. . .

Cynthia: I had become friends with Karen Grassle who was dating a good friend of mine. Karen, at that time, had just started performing in Little House on the Prairie. We were talking about how we wanted to write something; we wanted it to be important and not frivolous. We had independently come to meet a woman who was involved with a battered women’s shelter in Los Angeles. She invited us over to a safe house to talk to some of the women who didn’t mind talking about their experiences. The really distressing thing for us was finding out how many women had been stuck in abusive relationships because they were economically dependent on their husbands. There was nowhere for them to go, nothing for them to do. Most of them tolerated being abused themselves and it was only when their husbands began abusing the children that they would feel it was necessary to get out.

It was an issue that Karen and I were concerned with. At that time Karen was associated with the character Ma on Little House. The studio loved her. So it was an ideal time if we were going to get studio support. It was also a contrast with the character she played on Little House where the only thing that goes wrong was the weather or the crops, certainly nothing within the family.

We decided to write an account of a battered woman. We wanted to have enough characters so that any socio-economic level would be represented, so that it wasn’t just working class men that beat up on their wives. The first person we asked to be in this show was Mike Farrell who was doing M.A.S.H. He played a wonderful loving, gentle character on M.A.S.H. He had a relative who had been abused and thought this was an important topic. As we went on inviting different actors to be a part of this show we found that almost everyone we spoke to had been acquainted with someone who had experience with this issue. That was very shocking to me.

We asked Levar Burton and he said he was interested. We showed him a sample of the script and he said, “Oh typical, you’re making a Black man into a batterer.” We said, “No. All of the men in this story are guilty of spousal abuse and lack self control. But in fact, Levar, your character is the only one with a successful outcome.” We didn’t really know what we were doing but we wanted to have every possible outcome. One woman was going to die. One was going to get a divorce. One was going to go to counseling with her husband, that was Levar’s character. He was happy with that outcome.

Howard Duff, whom I had grown up listening to as Sam Spade on the radio, was the character whose wife dies as a result of her abuse. Mike Farrell played the husband whose wife ends up divorcing him. We found that, when we were preparing for a rehearsal all of the people involved—makeup, costumes, cinematography—would want to talk about the issue. So we would have, kind of, discussion sessions—talking at the beginning and showing the resources that were available at the time. I think it was an important movie at the time. I’m very proud of it.

Nanette: Do you think it had an effect on the larger population in bringing awareness to domestic abuse?

Cynthia: I was hopeful when it was going on the air that it was going to solve the problem. I was convinced of that. So of course I was disappointed when it didn’t. But I think it made a difference. All the local hot lines reported a lot of calls and visits. It probably did as much as a single show could.

Nanette: How was it working in a male dominated field?

Cynthia: It was interesting. At NBC at that time there was a great deal of support for this project and I’m not really sure why. It was a Monday night “movie of the week.”

Nanette: You and Karen wrote the script?

Cynthia: Yes. We had done a couple of storylines for Little House.

Nanette: Did you do other documentaries?

Cynthia: I did not. I always intended to. An organization grew out of the movie that still exists in Los Angeles. It’s now called Peace Over Violence. I was involved with getting that established and creating a board of directors for it, and working with the Santa Monica rape treatment program. I sort of left writing at that point.

Nanette: Are you a maker of objects as well as a cultural worker?

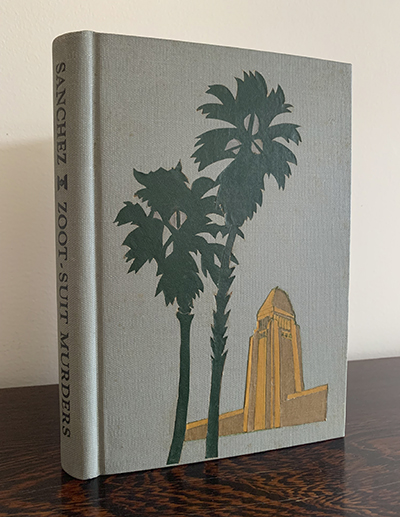

Cynthia: When I first met Frank [Buxton] he was a bookbinder. He had a bindery in Hollywood. I had come across an antique book that had become completely unbound. I took it to the bindery to see if someone could repair it. I met Frank. He fixed that book. I immediately went home and started looking for more books that needed repair. I took a bookbinding class with him. So I have bound books myself, and I collaborated with Frank on three or four. I never got good enough to do a full leather binding. I would do designs in book cloth with inlaid book cloth. People would get hysterical because you don’t take book cloth and make an inlaid pattern with it.

Nanette: I think now people are doing that. You are an innovator there.

One of the activities that you are currently known for is your extensive collecting of artist’s books. Do you recall your first encounter with an artist book?

Cynthia: My sister gave me Susan King’s Women and Cars as a Christmas present. It was a landmark book at the time. Then I was in San Francisco and went into an art gallery. I saw across the room what looked like a cave. I went up close and saw at the very back of the cave the figure of a tiny octopus. I asked the gallery owner “What is that?” They said it was “an artist’s book by Julie Chen.”

Nanette: There is a thread of the book in your life from that first book you took to get rebound and met Frank. . .

Cynthia: Here it is repaired by Frank. [Cynthia shows me the book.] It is a friendship book from the early 1800s by Emily D. I got excited at one point and thought it might be Emily Dickinson, but no, it’s not. Her friends would come over and spend time at the vicarage where Emily lived. Her father was a pastor. When her friends would stay the night they would write a poem or paint a picture directly in the book. It was a blank book, not a published book. The art done by these young people is breathtaking. Just so beautiful. The poems are not all that great, but they are charming.

Nanette: How did you come across this book.

Cynthia: It was in an antique store in England. I absolutely loved it and handled it so much showing friends and such that it became completely disbound. So I took it to Frank and he fixed it and everything else. [Cynthia and Frank married in 1982.]

Nanette: Were you collecting books at that time?

Cynthia: I just found this one. I have always loved books. My love of them evolved. Initially I was collecting old books and a lot of blank books that people had written poetry in or used as a sketch book. I started looking specifically for artist’s books after I bought Julie Chen’s Octopus.

Nanette: How did you come to found Bainbridge Island Museum of Art?

Cynthia: Frank and I were thinking of moving to Bainbridge Island from Los Angeles. Friends had told us it was the best place in the world and a haven for artists. So we came up to look and were looking around in town. We went into one little gallery and asked where is the art that this island is so famous for. They said, “Oh, it’s in private houses. You’ll get to know people and they will invite you in.” It was at that point before we moved here that I thought this island needed an art museum. There is no point in being an island devoted to art if no one can see the work. This was 1989. We had come up to visit Richard and Margaret Stine, but we wanted to surprise them and didn’t tell them we were coming and they were away for the weekend. We didn’t know what else to do so we bought a house.

Nanette: Is that the same house you are now living in?

Cynthia: It is. We were looking for a place to rent because we thought it was pretty terrific here, but there were no rentals available at all. This house had just come on the market. We had been driving around and it was raining hard. There are glass panels in the front door of our house, and you can look right through to the sliding glass windows of the living room. As we were walking up to the front door the rain stopped and as we looked through the glass there was a rainbow coming down into the water. Frank said, “That’s kind of blatant. I don’t think we can afford to overlook this.” So we bought the house.

I started talking to people to see if there was a way for the people on the island to share art they owned for a month. I was asking a lot of people about this, including my older daughter Juliet who had also moved to the island. Juliet is a horsewoman. She said, “Mom, if you want people to lend you their horses, first you have to show them that you have a decent barn to keep them in.” So we started a “barn raising.” It was as simple as that. It worked. I found it really invigorating. The artists are always so happy to participate. We are coming up on our tenth anniversary in June so I may have forgotten some of the drudge. It’s sort of like childbirth. I remember now that it was just the easiest thing in the world.

Nanette: How long did it take to break ground after you started fundraising?

Cynthia: To break ground? Just over a year.

Nanette: Wow. That is incredible. The museum is a non-profit and you were able to go that fast?

Cynthia: It wasn’t like I was standing on Winslow Avenue saying “We need a museum.” There was also a bit of serendipity because the museum site had just become vacant. People were talking about putting a parking lot there. It’s the first corner you see when you come off the ferry. I knew that if the museum was going to represent the town it needed to have a prominent place. I was able to buy the land on that first corner, and that was great. We have more parking lots than we know what to do with on the island.

Nanette: Did you run the museum initially or did you hire right away?

Cynthia: We hired Greg Robinson right away. He is now our superb head curator. As far as being an administrator, Sheila Hughes is brilliant in that role.

Nanette: So you were the vision.

Cynthia: Yes.

Nanette: What is the history of the Cynthia Sears Artist’s Books Collection. How has the collection developed and evolved over time?

Cynthia: I really didn’t think of it as a collection until Catherine Alice Michaelis started working for me. She was very clear that it was. I just thought they were books that I didn’t want to be very far away from, ever.

Nanette: So they were still at home.

Cynthia: Yes. The collection as a whole only just this year went to the museum for storage. They’ve always been a part of the museum, but they didn’t live there.

Nanette: But you have a display room for books with cases. . .

Cynthia: Yes. The Sherry Grover Gallery was from the very beginning intended to have nothing but artist’s books. The gallery is named after my closest friend who died a few years ago. She was an amazing person.

Nanette: Are you involved on deciding on the book exhibitions.

Cynthia: Yes for the books. Catherine Alice and I do all the book displays. A new one every four months. Every three years we are allowed to break out of the gallery and take the whole top floor of the museum with the books. That is when you really have a chance to see them. We have petting zoos to allow children to touch the books.

Nanette: Do you have a collecting agenda?

Cynthia: Anything I see that I love. It’s my greedy side.

Nanette: What makes an artwork successful?

Cynthia: If it captures the imagination of the viewer. Whatever that means. It has to stir the blood to be successful.

Nanette: Bainbridge Island Museum of Art has a specific focus on regional artists. Who are the regional artists that you find to be particularly engaging?

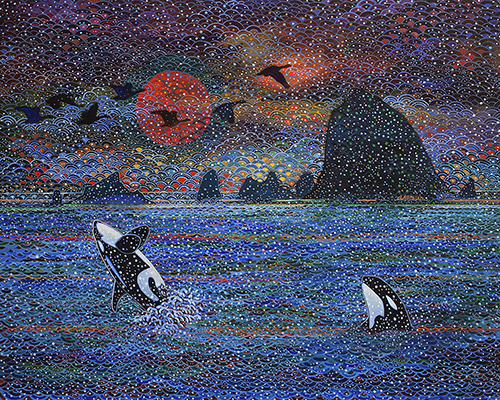

Cynthia: The first artist on the island whose work I bought was Gayle Bard. Her paintings are landscapes, but to me she is painting air. Early on, I bought two large pieces of hers, each one about 10′ wide by 8′ tall and they fill the room with a sense of fresh air! Another favorite artist of mine is Kurt Solmssen. Many of Kurt’s paintings are interiors, scenes of domestic life. He often uses his own home and family as his subjects. And still another favorite is a Mexican-born painter, Alfredo Arreguin who lives in Seattle. His work is simply magical.

Nanette: You show these works next door at a gallery called Yonder?

Cynthia: Yonder is our guest house next door. It is where we entertain. It is called Yonder because when we were building it a friend from the South kept asking, “How are things going over yonder?” Then everyone started calling it that. It is a guest house, a party house and a gallery.

Another Bainbridge artist I collect is Johnpaul Jones. He is an architect. He was the lead design consultant of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. The paintings and drawings I have of his are all animals. Beautiful paintings of local critters: birds, foxes, owls, ravens, coyotes.

Nanette: Why do you think Bainbridge Island is a mecca for artists?

Cynthia: It might have something to do with the fact that it was for a long time the summer home for Seattlites. They were people who appreciated art. It just seems to be a given that people care about art when they are on Bainbridge Island.

Nanette: What goals are you currently working on and what do you hope to achieve with them?

Cynthia: I want to ensure that the museum is absolutely solid. So I am working on the endowment. I don’t want it to be left up to any individual to have to rescue it.

I would like to do what I can to encourage people to collect artist’s books so that book artists have an audience that wants their work. I feel that collecting art/appreciating art is somehow somewhat passive because it’s all given to you right on the canvas. The reason I like artist’s books so much is because you have to read the book to get it. It invites you in and is a very active engagement. But just saying that doesn’t convince people that they should start collecting artist’s books.

Nanette: How do you think going to all girl schools impacted your life and your decisions?

Cynthia: I think that for women a single sex school is absolutely enabling. I was able to focus so much more on what I was learning and wanted to do with my life in high school and college than I ever did in grammar school. Obviously there is or should be a maturation that is taking place, but I was totally distracted by boys when I was in a mixed class. I never wanted to sound too brainy or compete with them. It was only when nobody was saying anything that I would raise my hand. So for me it was very liberating to not be conscious of myself as a maturing girl, and whatever that meant. I would recommend a single sex school in general, although my daughters went to public high schools. It’s funny I didn’t pass that belief or gene onto my girls and they have done just fine.

Nanette: It’s different times. . .

Cynthia: Yes. I just loved being in the all girl classes.

Nanette: Tell me a bit about your younger daughter Olivia.

Cynthia: Olivia is a poet and translator. She runs an organization in San Francisco called CAT, The Center for the Art of Translation. It publishes translations from an astonishing number of languages into English. They also publish a journal of original translations each year.

Nanette: What are some of your other philanthropic interests?

Cynthia: I love and support, as much as I can, all of the arts. I love theater arts, film, silent film, really any of the arts. But it is very intentional. I took a trip in a private plane and eventually felt very guilty knowing just what that one trip could do to the environment. I ended up making eleven gifts to organizations that protect the environment and analyze things like the ecological effects of our activities. That giving was about things I felt guilty about, giving to organizations that are doing important work. A lot of years ago everyone just thought everything was going to last forever, and one didn’t have to give it [the environment] a second thought. Man, were we wrong.

Nanette: Why are the arts important?

Cynthia: That’s like asking, Why is life important? It’s so huge to even approach as a question. It’s like asking, What is the meaning of life?

Interview by Nanette Wylde with thanks to Myrna Ougland, Catherine Alice Michaelis, and BIMA.

All images courtesy of Cynthia Sears, the artists, BIMA, or otherwise stated.