A Conversation between Bay Area playwright Sharmon Hilfinger and Katherine Bazak

As I sit across the table talking with Sharmon Hilfinger, I see the embodiment of two different women who are elegant, gracious, and intelligent. One is a wife, a mother, a musician; the other is an artist/writer committed to portraying her view of life and the world around her. As a playwright, she has chosen the theater to tell her truths under the guise of entertainment.

Theater is a tough art form to navigate. One must try to get their play off the page and onto the stage. It is impressive to meet someone with Sharmon’s track record. Her produced plays include three dramas and nine ensemble plays with music in collaboration with composer Joan McMillen. These have been produced by San Francisco Bay Area theatre companies, including The Pear Theatre, TheatreFIRST, Inferno Theatre, Menlo Player’s Guild, BootStrap Theater Foundation, as well as Heartland Theatre Company in Illinois. In 1998, she founded BootStrap Theater Foundation which develops and produces original plays by Bay Area playwrights.

Katherine: Let’s start at the beginning. I know that I saw An Ideal Mother some time in the early 90s. Was that your first play?

Sharmon: Well it was’t the first play I’d written, but it was the first play of mine that was produced. I read somewhere that The Menlo Players, at Burgess Park Theater in Menlo Park, was asking for scripts, so I sent it in. The director, Dean Burgee, called me immediately and it was produced in 1992. Beginner’s luck!

Katherine: Had you written anything before 1992?

Sharmon: I had been writing for a long time. I’m not quite sure how to say this—writing was my consolation prize for failure. I was an actor and I was admitted to the Conservatory program at Carnegie Mellon. It was, and still is, a University degree structured as a conservatory program, very unusual at that time. It was heaven! Theater classes all day, crewing shows at night—24/7 theater. It wasn’t easy to get in, and it wasn’t easy to stay in. They had a policy of accepting a certain number of students and cutting 10% of the class after the first year. It was very rigorous and class attendance was mandatory. I was there in 1970 when the Kent State Vietnam War protest killings happened. I cut classes to march on Washington D.C., which did not help my standing in the department. I’m sure there were other reasons (I was not given any kind of performance review) for why I was cut from the program.

That was traumatic! I was devastated. I came home and finished up my BFA in Drama at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington, Illinois (my hometown). IWU is one of those gems of a good liberal arts college and had a very strong drama department. I grew up getting my theater education there because I went to all the plays they put on—the Head of the Drama Department was surprisingly avant-garde. I finished my BFA in drama, but I had it in my head that I couldn’t expect to pursue a professional career in acting, I was a failure, this profession was not for me. So I gave up theater! My creativity had to go somewhere, and I started writing instead. I wrote a novel, and a number of short stories over the following years. Whatever my day job was, I would get up at six in the morning and write before I went to work. First thing in the morning is still the best time for me to write.

Katherine: You left theater and started writing, but you didn’t write plays.

Sharmon: That’s how deeply “being cut” wounded me. Theater rejected me, so I rejected it.

Katherine: So when did you start writing plays?

Sharmon: When my first child, Paz (also a playwright!), was about six months old, I was marveling at how much I loved this new person in my life. I had a lot of ambivalence about being a mother, so all these positive love endorphins were a surprise to me. Somehow, they unlocked the bolt I had secured to bar theater from my life. Suddenly, one day (I remember it very clearly), I said, “But I love theater! Why did I give it up?”

I had an infant, being an actor means spending your nights at the theater, I hadn’t acted for 15 years. I couldn’t see myself auditioning for parts, but I realized that I could write a play. And why hadn’t I thought of that sooner!?

I wrote a one act play and six months later I had a reading of it at the Palo Alto Play Reading Series run by Jeannie Barroga. Like the contact with Dean Burgee at Menlo Player’s Guild, Jeannie was local and the response was very quick. It was a good time to start writing plays in Palo Alto.

Katherine: Did you go back to school and take some writing courses? Best advice you were given about writing?

Sharmon: I took playwriting classes at San Francisco State and I got involved at the, now defunct, Eureka Theater in San Francisco. I took a workshop with Oskar Eustis, who was the co-artistic director with Tony Tacconi at the Eureka and they were in the process of producing Kushner’s Angels In America. That is where I met Ellen McLaughlin, a playwright/ actress who was the original Angel in Angels In America.

I took a playwriting class from her at the Eureka Theatre in the winter of 1990. It started out with a big group and as the weeks went on, there were fewer and fewer people, because Ellen had a very special style of teaching. I would call it beguiling! Instead of offering a bunch of techniques on how to write a play, she focused on the writing process.

The class whittled down to a small number of us who really wanted this and felt, yeah, this was nourishing to us. When it finished, we kept meeting once a week at one of the writer’s home in San Francisco. Ellen continued to meet with us, but she soon moved to New York. However, she stayed in touch with us and always joined us when she was in town. The group stayed together for years. It was all process-oriented. One of us would give a prompt, and we would all sit and write for 45 minutes and then read what we’d written. We could also bring in things that we were working on and share those as well.

That was the best writing group I ever had! I have remained in touch with Ellen; she has often read drafts of my work and discussed them with me.

Katherine: What is one of the most difficult things about writing plays? Ideas first or characters first? Do you map it all out in the beginning or do you write many drafts?

Sharmon: I’m a firm believer that everybody creates in their own way, a way that works for them. You know people have often given me books on how to write and I’m kind of embarrassed to admit that I don’t really want them.

Katherine: Do you feel that craft is important?

Sharmon: Yes! Craft is important, and you must have an understanding of dramatic structures. I had excellent teachers in the classes and workshops that I took, where I learned the fundamentals, but I regret that I didn’t have a more rigorous education as a playwright.

Katherine: Are you self taught? Would you say that most of your learning came from group readings and feedback, but also, maybe, from just reading plays and going to plays?

Sharmon: I’ve been involved in theater all my life. I acted as a child and by the time I was in high school, I was very serious about it. I was going to theater, reading plays, acting and directing. I learned by doing theater, I learned from the classes I took, and I continued to learn as I worked with directors on productions.

Katherine: I know you’ve written a novel because I remember reading it.

Sharmon: Oh yes, I have written two novels and the thing I’m writing now is probably a novel. It’s a very different kind of writing.

Katherine: Which one do you prefer?

Sharmon: I prefer the stage, probably because that’s what I’ve done the most. But also, because I do love the theater. When I’m writing a play, I’m always (in my head) in the theater. I’m seeing the characters on stage, I’m imagining how I want it to be. Sometimes, I am writing a character with a particular actor in mind, and that helps me create the part. It’s fun!

Writing a novel is much more about creating interior spaces. You’re describing the inner workings of your characters, you’re describing the room they’re in, or the landscape, and all of that description creates the mood. In drama, it’s the character’s actions/interactions that create the mood, along with all the work of the designers—the directing, the set, the costumes, the lighting. The playwright builds the motor for the play, but it’s the collaboration of all the theater artists that create the finished car “for the run.”

Katherine: It seems that language is a difficult medium to work in. If you have to create language for the actor, to create the meaning, the dialogue is really important, how do you write that dialogue? Do you keep a scrapbook a of conversations?

Sharmon: No, I don’t. But a lot of people do.

Katherine: How do you make it sound natural? So it doesn’t sound simple or cliché? Do you put yourself into the characters’ role so in essence you’re playing all the characters?

Sharmon: Yes, absolutely.

Katherine: Many Sharmons out there on stage! Really?

Sharmon: The trick is to fit the language to the character. For example, when I was writing the play about Emily Dickinson, there were a number of direct quotes from Dickinson in the dialogue. So, I had to make sure that the lines that I wrote for her matched her particular diction. Tricky!

Another time I was highly aware of speech patterns was when I was writing Arctic Requiem. I had been to Alaska to spend time with the Inupiat people, four of whom became characters in the play, and I wanted to replicate their speech patterns.

Katherine: How do you choose the topics for your plays?

Sharmon: The plays that I have done fall into two categories: feminist issues and environmental issues.

An Ideal Mother was about a young woman who had been adopted and she was searching for her biological mother. She is an actor in a play (Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan), and she wants to believe that the older woman playing Lady Windermere could be her mother, her ideal mother. Keep in mind that I wrote this play just after my second child was born. Clearly, I was working out what kind of mother I wanted to be.

A History of Things That Never Happened was a romp through great literary heroines: Catherine in Wuthering Heights, Anna Karenina, and Isabel Archer in Portrait of a Lady. The main character, Elaine, fantasizes scenes for each of these heroines in which they make one small change in their action at a critical moment, thus transforming them into empowered, rather than tragic, women. Elaine does this as she is reviewing her own history of relationships with men. A review of “things that never happened.”

The next play I wrote was my first collaboration with composer Joan McMillen. We met in Judith Komoroske’s Dance Studio in Menlo Park. Joan improvised on the piano for Judith’s dance classes and I was very fortunate to be in the adult class.

I asked Joan if I could try improvising on the violin with her on the piano, and she was game. We had a wonderful time making up music together, and soon we were talking about making a play together. Joan loved the story of the Imaginal Disks that are the cells in caterpillars that carry the instructions for the butterfly. Imaginal Disks became the name of the play. We wrote it as a coming-of-age story about a young girl, Franny, who is very imaginative, but not very good at school. Her father works for a company (not specified, but think Monsanto) that is genetically modifying corn to make it more productive and, in his words, “help save the world.” He is a single parent, and he would like to be able to modify/manipulate Franny’s behavior to make her more productive at school. Franny adores her father, but then she learns from her science teacher that the corn he is creating is killing the monarch butterflies. As Franny comes out of her pre-pubescent cocoon, she questions her father’s work and forces him to see the world in a different light.

This play followed a fairly traditional Musical Theater format, with songs interspersed with dialogue. I wrote the lyrics for the songs and Joan composed. She accompanied in the performances with cellist Moses Sedler and percussionist Judy Kasle.

Joan and I wanted to keep working together and we were approached by Bear Capron, who was the drama teacher at Castilleja School in Palo Alto. With Bear, we created a summer improv workshop for high schoolers in which the improvisations were all about environmental issues. After the summer workshop, Joan and I took material and created got water? The play takes place in a high school during a time of severe water shortage. The students are issued water canteens and have to line up for their allotment. There are those who follow the rules, and those who take advantage, and there is the corporation that comes in to take over the water supply and sell the rationed water. That’s when the students mobilize in protest.

The cast was made up of teens from local high schools and we took it up to the San Francisco Fringe Festival. We also gave two performances open to the public at Castilleja.

Katherine: What came next?

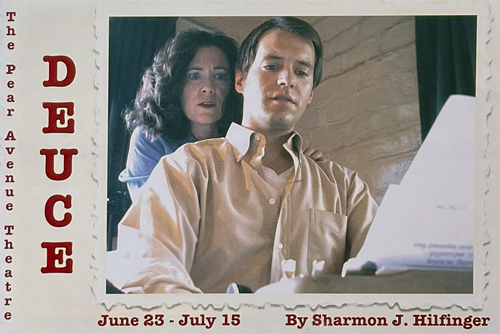

Sharmon: I had a production of Deuce at The Pear Theatre. This is a three-person drama, again dealing with feminist issues. The main character, Reddy, is a forty-year old academic who takes a sabbatical to write about her former professor who has died. She had a secretive love affair with him when she was his student. She arranges to do research in the professor’s writing studio with all of his papers, but arrives to find that his son is now living there. The son’s presence complicates everything. He’s protective of his territory, of his father’s legacy, and he’s very attractive. Reddy repeats the “older-wiser-lover” with the younger initiate, this time reversing the sexes. She also uncovers the unsavory truth that her professor had serial affairs with his students, that she had not been the only one. The relationship between Reddy and the son turns into competition over who has ownership of the father’s sullied story. And then Reddy discovers she is pregnant. It’s not a happy ending!

Katherine: I remember thinking of Wendy Wasserstein as l watched that play. . .

Sharmon: I’m flattered! But while that was being produced, Joan and I were brainstorming what to do next. When we finished got water? Joan said, “I want to do something that has to do with women. Women and creativity.”

After a lot of discussion we decided we wanted to work with famous women artists. Originally, we were going to have a bunch of women artists together in a play, but that was way too chaotic and we decided to do them one at a time. We chose Emily Dickinson and Georgia O’Keeffe, both American icons in their fields. They were very different people, from different historical times. Georgia was born exactly 18 months after Emily died. They were both affected by deeply entrenched prejudices against women as creative writers and artists.

We were interested in the struggles they had that were connected to their creative work. Emily worked mostly in secret, while Georgia became a very well-known artist in her lifetime. With both of them, there came a time of deep depression; with Emily it was possibly a psychotic breakdown. In both cases, hanging on to their creativity helped pull them out of these depths.

Joan and I saw emotional struggles in both of these women that were familiar to us in our own lives, our own struggles to make space in our lives to create, and an awareness that turning to our creative work had helped process and pull us through emotional difficulties. For us, it was affirming to get to know Dickinson and O’Keeffe; we were in such amazing company while we worked on these plays!

Katherine: In Tell It Slant, the play about Emily Dickinson, you introduced a kind of dance movement with a cord into the structure of the play. . .

Sharmon: Yes. This was when Joan and I really “hit our stride!” We didn’t want to stick with the Musical Theater format that we had used in Imaginal Disks and got water? We wanted the play to be an ensemble piece, with all the actors on stage all the time, playing multiple roles, lots of movement and the music woven into the fabric of the play. Joan was at the piano throughout the rehearsal process, and she started to improvise underneath scenes, creating musical commentary for the scenes.

She also wrote exquisite music to score the Emily Dickinson poems that were sung. This music stands on its own. We have lots of CDs, if anyone wants to hear it!

The cord that you mention was used as a prop throughout the play. It represented a line which could be all sorts of things: a laundry line, a line of poetry, the noose that Emily considers hanging herself from. It was a part of the continual choreographic staging that our director, Rachel Anderson created.

Rachel created an amazingly collaborative rehearsal room and out of this came the kind of ensemble theater piece that Joan and I had envisioned. I think that our idea of “ensemble work” was probably informed by our musical backgrounds. By this time, Joan and I were also playing classical chamber music together—small ensemble works that don’t rely on conductors, but rather very close listening among the members.

Tell It Slant was a co-production with BootStrap Theatre Foundation and The Pear Theatre in Mountain View. We later took it to the Fort Mason Center Southside Theater in San Francisco.

Katherine: So did you do Hanging Georgia, about Georgia O’Keeffe, after that?

Sharmon: Yes, we created Hanging Georgia with most of the same actors from Tell It Slant. We had a sense of “being a company,” something that is hard to achieve here, with the way theater work is structured as a gig-economy. We were not able to continue with Rachel Anderson as director because she had moved away. But we wanted to keep the same style of production: ensemble, music and movement integrated throughout, all actors on stage at all times so there was transparency about the process of telling the story. We were very lucky to get Jake Margolin as our director and he understood our aesthetic.

Joan’s music was often focused on creating a sense of the physical environment of the scenes. We were with Georgia as a young woman in Texas, so she had a kind of country-cowboy piece; at Steiglitz’s family homestead at Lake George, so there was a very lively roaring-twenties picnic song; there was an evocative New Mexico shaman-like song. Again, Joan was onstage, performing throughout, adding her improvisations as background to the scenes.

BootStrap co-produced this with TheatreFIRST at what is now called the Potrero Stage in San Francisco. We did it there first and then we remounted it at The Pear.

Katherine: I remember you had some kind of copyright issues with O’Keeffe’s estate.

Sharmon: Yes, you helped me with that! You were the one who told me we had to get permission from the O’Keeffe estate. Our original idea, (which in retrospect I thought, “thank God we couldn’t do that!”) was to have photographs of O’Keeffe’s artwork projected on a screen when she had scenes that were around the time she was painting a particular painting. But we were not allowed by the O’Keeffe Foundation to use images of any of her paintings. A blessing in disguise, because I think it would’ve totally upstaged what was going on, and that’s where everybody’s focus would’ve gone and it wouldn’t have worked out. Jake, our director, came up with the idea to use empty frames, knowing that people are familiar with her work. We had displays of her paintings (photos cut out of books we bought!) in the lobby. It really worked well.

Katherine: Then you and Joan did another ecological play, Arctic Requiem: The story of Luke Cole and Kivalina. You knew the main character in this play, he existed and his story is a very powerful one.

Sharmon: Yes, I knew Luke, very briefly. I’m a friend of his wife, who is an actor, Nancy Shelby. She came to me and said, “We’re going to Argentina. Do you have any advice about where to go?” It turned out that we were going to be in Argentina at that time and told them to please come and visit us. (I married an Argentinian and we live there for part of every year.) So Luke and Nancy came to our house in Argentina for three days. Before that I had only met him briefly, shook his hand once at the intermission of a play and that was about it. Luke, an environmental justice lawyer, was on a six month sabbatical trip.

During those three days he mentioned that the reason he was able to take a sabbatical was because he had finally settled this case in Kivalina. I asked him about the case and he explained that it was about this zinc mine that had completely polluted the water of this Inupiat Village in Kivalina, Alaska. Luke was a good storyteller. He talked about a meeting that he, as the lawyer for the people of Kivalina, had with the lawyers from the zinc mine in which they said that the mine would no longer be violating the EPA standards for polluting the water, so Kivalina (and Luke) would no longer have a case against them. As he pushed them for details on how they were reducing the toxins in the water, it finally came out that they weren’t changing anything in their water processing; they had convinced the EPA to change their standards so that their level of toxicity would be EPA acceptable.

That’s all I knew about Luke and Kivalina.

We had such a good time together and he was going off to Antarctica and then to Africa and we said good-bye and we’ll see you in June when you come back to San Francisco. We were all looking forward to continuing this friendship. Then on June 9th, I got a telephone call that he had been killed and Nancy had lost an eye in a car accident in Africa.

We went to his memorial service at Cowell Theatre in San Francisco. The place was packed! There were so many people who spoke, including a delegation from Kivalina who came to honor him. Toward the end of the service a speaker asked that anyone in the auditorium “who feels that their life has been affected by Luke Cole to stand up,” and everybody jumped to their feet! I had not realized that he was such a huge force in the environmental justice movement. His passing was a significant loss to the environmental justice movement. Not long after that, I wrote to Nancy and I said I would like to write a play about Luke and Kivalina but I wanted to check with her, is this okay? Her response was, “It’s okay but I can’t have anything to do with it.” By the time Joan and I got around to actually working on the project, Nancy was involved. She put us in touch with Luke’s colleagues and with the people in Kivalina. Joan and I went to Kivalina and stayed in the house of one of the villagers for a week. As it evolved, Nancy became very, very involved and then became my co-producer. She helped put together the creative team. She was the one who brought Giulio Perrone to the team as set designer, and now Gulio is a part of my life. Which was a good thing!

Katherine: The play was so beautiful especially the way you meshed the reality of the issue of pollution with the spirituality of the native people. You had that wonderful actor who played the Raven. He was a dancer so you got this wonderful dance movement into the play.

Sharmon: Yes. That was probably the hardest play that I’ve done for multiple reasons. Joan and I had the aesthetic that we had created with Tell It Slant and Hanging Georgia. The “company” with those two productions were all younger people, they were open to trying something that was different than what they had done before. With Arctic Requiem, we had very seasoned actors and a director, whom we discovered as the process unfolded, didn’t really share our aesthetic. So, there was a lot of tension in the rehearsal room.

That said, Arctic Requiem was our biggest box office success. I guess the tension pushed everyone to make it work.

Katherine: We didn’t talk about your play The Gods Must Be Crazy: A Dark Comedy for Dark Times. Why did you write it?

Sharmon: That came about because of Giulio Perrone, who was the set designer for Arctic Requiem. He also has his own company, Inferno Theatre, and after Arctic Requiem closed, he came to me and said, “I’d like to keep working with you. Write something and we’ll produce it together.”

The last three plays that I had written had all been about real people: Dickinson, O’Keeffe, Luke Cole and the people of Kivalina. I was ready to write something where I was not beholden to the constraints and details of being historically accurate. The mythological Raven was one of the characters in Arctic Requiem that I really liked; Raven is a trickster and a lot of fun to play with. He is also part of the creation myth of the Eskimo people. And there was a character in Tell It Slant, Demiurge, that I felt I wasn’t finished writing about. So I started with those two characters and let them kind of inform me about what I might write.

The premise became the gods are not happy with what humans are doing with the earth’s environment, so they get together to figure out what they need to do. I decided to assemble a diverse group of gods. I started finding all these weird gods, like Lui Hsing the Chinese god of jobs, salaries and fortune; Dhumavati, the Indian god of poverty; Pachamama an Incan earth mother; Ra, the Egyptian sun god. The play’s conceit is that these gods are appalled by the human-related activities impacting the earth, but can these gods help the situation or would they be just as unruly as the humans? Ultimately, the gods kidnap two powerful men (unnamed, but they really resembled the Koch brothers) in their efforts to regain control of the earth’s environment.

This was a co-production of BootStrap and Inferno. Giulio directed the production and Joan and I were the musicians on piano and violin. We had not originally planned it that way, as Giulio had asked a wonderful Persian percussionist to provide the music/soundscape, but he pulled out right before we started rehearsals. So, Joan and I created some music and pulled together other existing music. It was an eclectic mix of music to accompany these diverse gods.

Katherine: How did this play come to be performed at the Brower Center in Berkeley?

Sharmon: Well, as Giulio and I were planning the production, we were looking for a venue in the East Bay. I went online and found the Brower Center in Berkeley. I contacted them and said, here’s who we are, we are doing an environmental play and could we do some performances there? It would be perfect. The executive director wrote back immediately and said yes. It was another one of those convergences that are so empowering when they happen so easily. We performed it there one weekend, and the other performances were at the Preservation Church in Oakland.

At the Brower Center we were looking for a way to make this more than just a theater performance, we wanted it to be a community event. We invited a panel of environmental leaders to speak afterwards. Ingrid Brostrom from Luke Cole’s environmental law firm, The Center for Race, Poverty and The Environment; Sumona Majumdar, Executive Director at Earth Island Institute (which was founded by David Brower); and Dr Janice L. Kirsch, MD, MPH of The Climate Mobalization. They each talked about pressing environmental issues that their organizations are working on. It was very well attended, which was gratifying.

Katherine: I know writing a play is hard but ultimately you have to get it produced! Was that the impetus for BootStrap?

Sharmon: Yes. I took on everything when I started BootStrap. I had to because, quite honestly, I had this huge hiatus in my theater career. When I started writing plays, I had absolutely no network at all, nothing. You can’t do anything without a network, especially in theater, because you rely on other people to create a play—it’s not just you, the writer, sitting alone in a room.

I mentioned earlier that I was taking classes at the Eureka Theatre while they were producing Tony Kushner’s Angels In America. Around that time, we went to a fundraiser for the Eureka and Tony Kushner was there. I asked him where he would recommend I send my plays. He said, “Produce them yourself!” I took him to heart.

It was about a year and a half later that An Ideal Mother was in rehearsal at Menlo Players. Dean Burgee let me sit in all the rehearsals and participate in some of the design decisions. After that experience, I said, “Okay, I can do this, I can produce a play.” I founded BootStrap Theater Foundation in 1998 in order to produce A History of Things That Never Happened. And, of course, I was completely naïve about what I was getting into!

So for me, the hardest thing in writing a play? It’s getting it all the way to the stage.

Katherine: You have had plays at Zspace, at the Magic Theatre, The Pear and other venues in San Francisco.

I think that’s amazing because I know it’s not easy, it takes a lot of pushing and drive.

Sharmon: And a lot of fundraising!

I always say doing a play, the way I have done it, where each time we have to raise the money, find the space, hire all the artists, build the set, make the costumes, run the rehearsals, create all the marketing, sell the tickets—it’s like a start up. You have to start everything up, build the product, and then it has a shelf life of four weeks. It’s insane, and I love it!

Katherine Bazak is a painter who works primarily with the human figure. Its potential for change, movement and intellect appeal to her optimistic view of life. She finds the figure to be a fascinating subject that demands close observation. She has a BFA in Painting/Printmaking from Virginia Commonwealth University and an MFA in Painting from the University of Wisconsin.