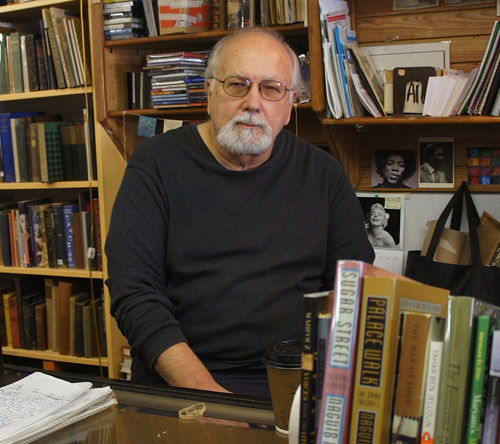

Beau Beausoleil is a San Francisco-based poet and the proprietor of the Great Overland Book Company, which is located in San Francisco’s Inner Sunset neighborhood. Beausoleil has written more than ten books of poetry. His most recent collection, Ways to Reach the Open Boat, was published by Barley Books, UK in 2013.

In 2007 Beausoleil read an article in The New York Times about a car bombing on al-Mutanabbi Street, the historic bookseller’s street in Bagdad. This incident inspired the creation of the al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition, a project which currently has five distinct components: 130 letterpress printed broadsides; 260 artists’ books; a publication of poetry and prose titled Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here; the coordination of poetry readings around the world each year on the March 5th anniversary of the bombing; and most recently Absence and Presence, a call to 260 printmakers for the creation of fine art prints.

The project involves hundreds of artists who have created work specifically as a response to the 2007 bombing; and extensive local and international exhibition schedules, much of which Beausoleil coordinates himself. Complete editions of the visual art responses will ultimately be donated to the Iraqi National Library in Bagdad.

We met in early February over a cup of tea at Beau’s kitchen table.

Whirligig: What is poetry?

Beau: What is poetry? At one point in my life I stood on the corner of Powell and Geary, it was real close to Union Square not that far from Macy’s, and I had a little box next to me on the ground that had a sign that read “Support your local poet.” I would give out multiple copies of a poem that I had printed out to anyone who would take them. They didn’t know that they were poetry. My secret hope was that some patron would appear out of nowhere with a wallet, but of course that never happened.

I usually made enough to print out the next batch of poems. Some people would avoid me. They would go out into the street thinking that I was handing out a religious tract or a political tract of one kind or another. Some people would take them. I’d see them read them. I’d see them crumple them up after half a block and throw them away. But every now and then something would happen. I remember this one guy who took a poem. I watched him walk down Powell and I could see that he was reading the poem. He got about three quarters down the block. He turned around and walked back to me and said in this agitated voice, “I don’t know what this means, but this one line, that speaks to my life.” That’s poetry.

One time I was part of a group that was visiting Folsom Prison where there was a writer’s workshop. The visitors would read and then the prisoners would read. During the break this guy came up to me and said, “Are you Beau Beausoleil?” And I said, “Yes.” He said, “Did you have a poem in . . .” and he named this small magazine, and I said, “Yes.” He said. “Did it go like this. . .” and he recited my poem back to me. I was pretty stunned. He said, “I just wanted to tell you that that is the poem that started me writing.” That’s poetry.

Lorca, the Spanish poet, tells a story about duende. Duende is the inexpressible in art, in beauty. It’s there and you can feel it. Some people can recognize it. It’s an important part of the life of any artist who is really at that point. He tells a story to illustrate it.

There was a flamenco contest in this basement in Spain. All these young women are assembled. They are all in their 20s and beautiful. They are getting ready to go on the stage to perform before these three judges. Suddenly the door opens. A woman in her late 50s walks in, walks straight up to the stage, throws her arms in the air and the judges declare the contest over because they could see that she had duende. That’s poetry.

Poetry is something that gives you back part of your own life. It allows you to see your own life in another form, another way. That’s what poetry is.

Whirligig: What makes a poem successful?

Beau: I like poetry that is useful in the best sense of that word. It can be a very intangible thing, but it’s useful to you in that way. That’s what makes a poem work. There’s a famous story about somebody coming up to Robert Creeley, the poet, after a reading and saying, “You know that last poem that you read, was that a real poem or did you just make it up?”

I started out a very strong narrative poet and then my poetry started to break up and become more abstract. There is a thing about poetry — people want to identify with the poet and the poem. A lot of people write really good narrative poems. I call them toaster poems because they are a poem that somebody can come up to you after the reading and say, “I had a toaster that was just like that.” And you can start a conversation. With other poetry, that is more abstract, there is no toaster in there. People are left with a particular feeling or they are carried to a particular place in their own lives and reflections, but there isn’t anything for them to talk to you about. So a lot of times your poetry can be successful but you never get any feedback on it at all.

Whirligig: Or a conversation?

Beau: Or a conversation. And all poets want the conversation. All poets read because they want that feeling that they are connected. Even the most abstract ones want that feeling. It just doesn’t necessarily always happen.

Whirligig: How did you come to be a poet?

Beau: I came to be a poet by a very circuitous route. I was working on a ship in the Pacific Ocean. I started writing haiku. I’d been on a little vacation to Japan. I like Japanese culture. I was fascinated by Zen Buddhism at the time. I was in my early twenties. My idea of a poet was that you had to be dead, number one, preferably that you had died in the nineteenth century, even better. I did not know how to be a poet. All I saw were the classic poets and the academic poets. One day I wandered into the library in Honolulu. Hawaii was our homeport. I ended up in the poetry section. I don’t know why. I picked up a copy of Robert Creeley’s For Love. It was poetry in the vernacular, everyday speech. That was my way in.

One thing that poets do is they give each other permission. They open ground and give permission for somebody else to do something different than they’ve been doing. This is probably true of all artists as well.

He gave me permission and I started to write in the vernacular. It was wonderful. It was a gift. So that’s how I started.

For about the first seven years I learned how to write from what I call the wrist down. The poetry didn’t really have anything to do with my life. It had to do with my concerns, but not necessarily my life. Then there was an upheaval in my personal life and poetry just kind of rushed right up my arm into my whole body. That was the point when I really began to write poetry.

Whirligig: To express what you were going through?

Beau: Not so much to address that particular upheaval, although some poems did, but somehow altering my emotional landscape. It again gave me permission to alter the kind of poetry I was writing. My first book only has poems from that point onward. All the years before that, and I wrote a lot, didn’t really have anything to do with me in a way. But then I could feel that they did. I bet that’s true for a lot of artists. You just know that is the real starting point.

Whirligig: How do you read or approach a poem?

Beau: Just open. I have no fixed expectation. I just begin to read it.

A lot of times poems and poets can be different things. I remember once when I first came to the city I was at a reading at the library. There were a number people reading. There was a guy in front of me that was pretty obnoxious — talking when people were reading, he was just being rude, and he was halfway drunk. Then all of a sudden they called the next reader and that guy stands up and goes up and he reads the most extraordinarily beautiful poem. I had to grapple with that. That this is somebody I wouldn’t necessarily want to be in conversation with but he was a helluva poet.

Likewise, I remember one of the first times that I saw a letterpress broadside. I was at book fair and there were these broadsides up. I had not really encountered broadsides before except as images in books, but here I was physically in front of them. I probably read half of the poem on the broadside before I realized it was terrible, but the broadside and the printing were so beautiful that it overcame how lacking in poetry the poem was. I thought: Whoa. That’s a pretty powerful art that can do that.

There are a lot of things to take into consideration when you read a poem. You bring your own experience to any poem that you read. I try to come to a poem with generosity.

It is partly to praise poetry and damn it at the same time, but poetry is really an equal opportunity employer. Anybody can write a poem. It doesn’t necessarily make it a good poem. You have to read poems to find out. The other thing about published poetry is that you not only have to be a good poet, but you have to be lucky at the same time. That’s another thing about the arts in general. There are plenty of really fine poets who have manuscripts in their desk drawer that they have never been able to find a publisher for. They just sit there and we won’t ever know about those people. Luck plays a great deal in who we read, and who we get to read.

Whirligig: What is the pulse of the San Francisco poetry community? Who is reading? Who is listening? Who is paying attention?

Beau: When people buy poetry at my bookstore I always ask them, “Are you a poet?” because frankly I think the only people who read poetry are other poets. And when they say, “I’m not a poet.” I go, “Oh my god, just a pure reader, this a wonderful to encounter.”

I think that poets are aware of the San Francisco poetry community when they need it. When they need a kind of social support. You become aware of other people who are writing in the same way that you are, or you go to workshops or readings. They do tremendous work in supporting each other. They publish each other’s work. They have gatherings of poets. They write about poetics. It’s never been lacking in San Francisco. I can’t give you a specific answer but I know it is there and it’s alive and healthy.

There’s a certain point where that’s not as necessary anymore. I just got to the point where I didn’t need that. I didn’t need to follow what was the most current. I had my own work to do on my own craft and I just did it.

Whirligig: There is a marked shift in the style of your writing from Witness to Aleppo, two collections that are only eight years apart. Talk about this evolution of style and the distinctions between them?

Beau: After a couple of books of narrative poetry I had this desire to strip things away. It was around the time of the language poets in San Francisco. I still had the narrative impulse and there was still narrative in there, as disjointed and disconnected as it might look or sound. I was still a narrative poet in that area. The unfortunate thing was that I was too narrative for most of the language poets and working with language too much for most of the narrative poets so I was kind of on my own ground. Although I can find kinship with people at different times. It was just really an impulse. I wanted to see how close I could get to a kind of utterance that still had a musicality to it. I still wanted to hear that music that is in poetry and that is in language. As soon as I stripped it down I brought it back with some of that fragmentary nature that still exists in my poetry. I’ve come back up to a lot more narrative than I was in something like Aleppo.

Whirligig: Aleppo feels to me like it’s a single poem.

Beau: Could be. It could be a poem in parts. It could be a life in parts. Although even in that there’s one long fragmented narrative piece called The Procession of 100 Horses.

I chose Aleppo because Aleppo has always been a city that people pass through. They were usually on their way to pilgrimages, or conquerers. Everybody that passed through left something of themselves. I was drawn to that idea. It was really important to me at the time. It’s terrible what Aleppo represents right now and what’s happened to it.

Do you have it here?

Whirligig: Yes.

Beau: What’s your impression?

Whirligig: I feel like I am missing context with Aleppo. In Witness the poems are very sensual and I feel very much about being on this planet, being in the body, the sensuality of our interactions. With Aleppo I feel like it is more about the historical nature of the place and about warfare. It’s not?

Beau: No, but your comment makes me think that it’s more about the landscape of our own minds. It’s very interior. It’s very much in the brain as opposed to Witness which is very much about the senses in the body. Aleppo is a very interior book. There is a lot of violence, but it’s not about Aleppo itself. It’s more interior.

There’s a way that you, as a poet, guide language; and then in Aleppo there is an attempt to let the language guide me. That’s what I would say.

You are part of every poem that you read except when the poem excludes you. Sometimes the poem is so polished and so beautiful it won’t let you in. It wants you to admire it.

Whirligig: Do you mean in a self-aware, pretentious sort of manner?

Beau: Yes. That makes me think of another story. There’s a poet named James Wright. James Wright in the 1950s was an academic who wrote academic poetry as you might imagine it — thick, thick, sometimes impenetrable, but beautiful. And then his marriage broke up. He was at a really low point. I don’t know how but he knew Robert Bly who in the late 1950s was a real wild man of poetry. Bly said, “Come and live with my wife and I on this farm.” So he did. He wrote a book which is called This Branch Will Not Break. It is just the most beautiful book because James Wright suddenly was in touch with all of the senses in his body. He has a wonderful poem about lying in a hammock on William Duffy’s farm and he talks about being in the hammock and looking up and seeing the birds. He talks about what he hears, what he sees on this summer day. And the poem just kind of moves down, moves down, and then finally the last line comes out of the blue and he says, “I have wasted my life.” And phew. It just goes right into you. Then after he got back on his feet he went back to writing the same kind of poetry he was writing before.

Whirligig: What is the nature of your writing practice? Are you disciplined or ?

Beau: Because of this project I am involved with (The al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition) I have only started writing again after a couple of years. I would write one poem a year just so they wouldn’t come and take my poetry card away from me, so I could stay a good union member, in good standing with the poetry union. But lately I’ve started writing again. I don’t know why. I would look longingly at my notebook but I would walk past it. Then all of a sudden I just couldn’t ignore it anymore and I started writing again. Maybe even two years ago I began to write more. Now I am writing a lot. I had a book come out last year with a publisher in the UK that I really like a lot.

Whirligig: What’s the title?

Beau:i It’s called Ways To Reach The Open Boat from Barley Books. It’s a letterpress book. Do you want to hear that poem?

crossing

there are ways

to reach

the open boatbut each moment

is less certainthere are ways

through the ruins

of the tonguebut then one is stranded

in the visiblethere are ways

to reach

the open boatbut I cannot contain

my memory

This poem has both the fragmentation and the narrative impulse. It’s between that place of being graspable and ungraspable. It’s open enough so that you can push your own life into it. That’s what I like so much about the way I’m writing right now.

Whirligig: I have been responding to the poems that you attach at the end of your emails because I can go into them.

Beau: That’s the place that I want to be at, where I can bring the way I see things now, but still have that opening for somebody to step into.

You know the thing about writing, and it’s probably true about all art, is that you have to really work to get into that space where it becomes effortless. The thing is you can’t stay there. That’s the strange thing. You have to come back out and then you have to work your way back in again. It’s an exhausting, exhilarating process. I think a lot of people have a sense that a writer just stays there or a poet just stays there, but from my experience it’s impossible to stay there. The highest compliment that a poem can give to the poet is to kill them and keep them there. That’s why you have to leave all the time. You have to come back here into the every day, and then want to go back again, and get as close to that as you can.

Lesson

Trying to pull

yourself back along

the words

trying to get close

to what holds

the flesh to them

So you talk

over the words

You shout

to the words

And the words

sometimes begin

just begin

to drag you along

like a bad leg

to carry you

to a place

where they can

turn and knife like

skin you

into other words

and move you closer

try to kill you

keep you there

or let you hear

however briefly

their deadly harmony

Whirligig: Words are powerful.

Beau: They are.

Whirligig: You have mentioned that one of your favorite poets is Paul Celan, whose work is predominantly about the Holocaust; you have a collection titled Aleppo, a Syrian city with a long history of political dissidence and upheaval; and now you have founded The al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition which is a many fold creative collaboration responding to the 2007 car bombing of the booksellers’ street in Bagdad. Tell us about your attraction to or interest in these areas of human strife.

Beau: When I wrote about Aleppo it was a passing through place that’s how I saw it. It wasn’t really about a place of strife.

My attraction to Paul Celan was on a couple of different levels. He was also really breaking up the language. I use to say that one of my aims was to take the diamond that was the poem and put so much pressure on it that it turned back into coal. Because then it would be useful. Celan’s poems always seem under pressure. Now that pressure for him came from the Holocaust. It wasn’t that I was drawn to that fact or the fact that he lost members of his family, that he was in a work camp. One of the things that I admire about him is that he was originally from Romania and German was not his first language. German was the language of culture. People read in German and sang in German and everything else. He really saw the German language as the language of the oppressor. After the Holocaust and the war ended he made a conscious decision to continue to write in that language, to confront in a sense, the language itself with what it had done, and what people who carry that language had done to others. I just admire that that he would do that.

Whirligig: Did you read him in German?

Beau: No. I’ve read him in English, in translation. About six years ago Andrea and I made a little pilgrimage to the last place that he lived in Paris. He committed suicide. Of course there was no marker or anything, as great a poet as he was. It was wonderful just to stand and walk on the street that I knew that he stood and walked on. Andrea and I named our daughter after him. Her name is Celan. I was drawn to him but not because of the war, but that the idea was one more aspect of the function of language — that you could investigate the very language of those that oppressed you.

I was drawn to the project, and again maybe the similarities here are that the language of my own country kept me at a distance from Iraq, and what was going on in Iraq, and how to respond to what was going on in Iraq. When the bombing happened on the street where I am knew that my bookstore would be if I was an Iraqi, and as a poet I knew that would be my community, that distance just dropped away and I started the project.

Whirligig: You have previously stated that you started The al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition because you were waiting for someone to initiate a response to the bombing (on the local level) and it just wasn’t happening. Why did the bombing of al-Mutanabbi Street resonate with you to the degree that it has?

Beau: Right. I did wait for somebody to do something. I am not an organizer. I’m the guy in the back of the room that always asks the question that upsets somebody. But I knew that there had to be a response.

Whirligig: Initially you were looking for a poetry reading?

Beau: Initially. Right. (laughs)

Comparative

here is a

remembered wayto read

at the tablehere is a way

to curse at moneyto swear

in a ritual kitchento remember

each lodgement

of an intimate tongue

Whirligig: How does the response — artists’ involvement and community engagement — and the current scope of The al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition projects compare to your initial imaginings? Talk about your vision and how it has developed and how it has affected you personally.

Beau: I would say that it developed in a lateral way. I certainly had no idea that it would be what it is today. That it would be as big as it is and have so many parts to it. We’re entering the seventh year. We’ve been pretty far below the media radar in terms of noticing what we do.

It’s affecting me deeply personally through the friendships that I’ve made — with the conversations that I’ve had with others, with my understanding of the Iraqi cultural community, with an understanding of what it means to attack a shared cultural space. What that means historically. It’s been really important for me.

At this point in working on the project, I don’t remember that I started it for the most part. It’s just something that I do, but I don’t think of myself as the person who began this. I have no idea where it’s going to go. Obviously I can’t do it forever. We’ve moved people with this work and it continues. My feeling is that we are clearing out this space where I feel the Iraqi cultural community will see us with some respect. My feeling is they don’t have any reason to want to have anything to do with us. They have every right in the world to look away. The project was started by somebody who lives in the country that invaded them and occupied them for eight years. The aftermath of what we did continues to reverberate throughout Iraq.

Everybody wants resolution you know. They want things tidied up. But there isn’t anything tidy about the project really.

People want a goal. They want a goal that can be accomplished. One metaphor that’s often used is: If this project were about putting a glazed doughnut in the hands of every child in Baghdad there’s no doubt in my mind we would have high school seniors all across the country baking doughnut and loading them into a truck. Why? Because once the doughnut was baked you’d have done your part. That’s not what this is about. I want people to have a sense of personal responsibility, a self-examination of themselves through what this project does and what their relationship is to people who are portrayed as the other. I want them to see the commonality between any Iraqi artist and any artist here, any cultural institution in Iraq and any cultural institution here. That we all stand on the same street together, a street that happens to be called al-Mutanabbi. It’s changed my life completely. I’m grateful for that. I wish I could do more with.

I remember once when I had written a project update, and god knows I write a lot of them. I got an email from a friend named Maysoon that her friend had a friend that was an activist in Bagdad who was taken off the street and died in jail. I just came into this kitchen and I started to weep. I thought: how useless we are. I started this project going and we can’t stop the death of somebody who’s protesting a corrupt, unrepresentative government and I can’t do anything.

I wrote to Maysoon and I said, “I want it to stop. I don’t want to do this anymore. I can’t do anything. I can’t accomplish anything.” She wrote me back and she told me how important it was and what the project was. I understood what she said. The project’s more important than what I feel. It’s more important than how helpless any one of us feels individually. It is a collective voice and it is to some people an irritant. That’s one of the things I like about it. We’re not going to allow the page to be turned on the bombing of al-Mutanabbi Street and all that that contains. You can see in that one bombing the entire war, number one. I always say to people that I don’t want this project to be seen as an anti-war project because I don’t want it to be pushed to the side as one more anti-war project. I say we’re not a healing project. We are a project of witness and we’ll continue to be that.

What we are doing is expanding the whole idea of al-Mutanabbi Street to cultural streets around the world, and to cultural workers around the world. I think that’s a really, really important part of this project.

Whirligig: You think it is a war on culture and intellect and difference?

Beau: I think that it’s a struggle/war for power, and one of the casualties is always culture and cultural workers. So we are a response to that. You don’t have to directly go after culture, but it will be one of the targets on the side as well. Being able to see yourself through your culture is a very important thing. It’s a thing that brings people together, so yeah, why not dismantle that while we’re doing everything else. Why not just eliminate the books that we find offensive, but why not instill a kind of fear in writers and artists and academics so they hesitate before they do something, before they write something. In that way they can do our work for us. And we have that here in this country. We have self-censorship in academia. This is something that this project addresses along with everything else.

Whirligig: In homes we have self-censorship. That reminds me of one of the stories in Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here. A woman is talking to a bookseller and he is telling her about how they blew everything up. She realizes later that he was talking about an event that happened 700 years earlier. It is just so much a part of our history to annihilate and destroy everything that we don’t want to be part of whatever the current regime is.

Beau: Yes.

Whirligig: In your emails to the participants you have expressed the desire that venues exhibiting the project engage in community outreach and be somewhat aligned with a specific project agenda or aesthetic. Talk about this concept. Why is this important?

Beau: This project is composed primarily of visual art at this point — the artists’ books, the broadsides, and now the printmakers. I don’t want this project to turn into an art exhibit. I don’t want somebody to come in the front door, glide along exhibit cases and go out the back door. Things have to be uneven. We have to make the floor uneven in a way. We do that by asking exhibitors to hold readings or a panel. I try to involve the exhibitors so they don’t have that exhibitor distance from the actual exhibition. I can’t control what they do. But I can comment on it if they ask me to. We don’t have a rigid agenda but we do want context. That means trying to contact the Arab American community around where the work is being exhibited, trying to work with Arab American writers and artists, and keeping in touch. It’s just trying to do things and that’s what I ask. Here are some possibilities that you could try. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.

Sarah Bodman, who is the UK coordinator for the broadsides and the artists’ books, and I made a decision about not publishing the names of the artists who were in each exhibition. This was not something for their CV. This was a collective voice. We didn’t want people to feel disappointed, “Why isn’t my work in a particular exhibit?” Our feeling was that we would publish any announcement sent to us by an exhibitor, we would send along every review and photos. But we were not going to publish names. This was a philosophical point. There was a group of people that got very angry about this. We told them that if you write to one of us asking if your work is in a particular exhibit we will write back telling you if you are or aren’t, but we don’t want to publish names. This wasn’t a huge group that did this. One thing that I got more than once was, “If I knew if my work was in the exhibit than I could invite my friends and people I know who live in the area.” My feeling is why wouldn’t those friends go even if you weren’t in the exhibition. Isn’t that what this project is about? To see this work and to think about this work? My feeling is that even if you are not in a particular exhibit, you are in the exhibit because the only way we got the exhibit is because of the body of work that has been created, and you are part of that body of work.

Whirligig: I think part of this relates to what you were saying at the beginning of our conversation about all poets wanting a conversation about their poems. It is just that these are visual artists who want a conversation. I think it is challenging for those of us in the Western world to think of ourselves as part of a collective. I also think that some people might not have yet embodied the concept of witness.

Your Standards

five trucks in a row

are an unmistakable

sign of cool days

and late nightsyou understand loss

as a version of luckas something exacting

under the lamp of

nightmarepeople are often happy

in the summerthese are your standards

Whirligig: In the broadside aspect of the project there are 130 participants, one for each of the individuals who were injured or killed in the bombing. For both the artists’ book and fine art print aspects of the project you have sought 260 participants. Why double the number? How is this number significant?

Beau: My feeling is always (through the arts) to keep what is happening in Iraq, the Middle East and North Africa in the forefront of people’s minds. We originally planned to get 130 artists for the artists’ books response. Then we got there. I wrote to Sarah and asked her what she thought if we tried to get to 200. She wrote back something like “Sure. Why not? Let’s keep going.” So we issued another call. Then I asked her what if we got to the symbolic number of 260? She’s always been game. When I first got the idea for the artists’ book project I wrote her and I told her why I wanted to do it and I asked her if she would be co-coordinator on it. I finally ended my email by saying, “Is this crazy, you know, in terms of what I am taking on here or what we are taking on.” She wrote back and said, “Of course it’s crazy. Let’s do this.” That’s the kind of people I want to work with.

So when I decided to do the printmaking response I wanted a body of work that big. We can split it up and have 50 prints at a particular gallery and that will carry enough internal emotional weight to push across what we’re trying to get at. I don’t want an exhibit so small that the work begins to be examined on an individual basis in a strange way. That’s not what we’re about either. I also think that the work informs each other when you have at least 50 pieces.

Taking on the printmakers. . . I try not to think about it too much, but I have learned some things. This time I sought out a whole bunch of coordinators. Now we have six coordinators including one in the UK, and one in Australia who covers Australia and New Zealand as well. We really want one in the Middle East, and one in North Africa. It will happen or it won’t happen.

Whirligig: Would that be a risky position for someone?

Beau: Yes. When we sent out the material for the show in Cairo it was held by customs for 10 days. I really sweated that out. I thought somebody is going to see something. In the books and broadsides there is blood and references to blood and references to a car bombing. I thought: oh god. And then they let them through.

I can’t think of a more perfect time for it to be in Cairo than at this moment. A project that’s about the free exchange of ideas and personal freedom. We’re going to open there March fifth so that will be great. I want to show in other places in the Middle East but it has not been easy to find places.

Whirligig: Are they having readings in Cairo?

Beau: Yes. On March 5th it will be the opening day of the exhibit and Sinan Antoon, an Iraqi poet from our project, is going to be the keynote speaker.

Whirligig: Would you say the project is actually about the free exchange of ideas and individual freedom?

Beau: It’s one of the things. It’s about a number of things really. When I was in the UK the BBC radio wanted to interview me so they did what they call a preliminary interview on the telephone. One of the questions the person asked me was “What is your goal?” I said “We don’t have any goal.” It really bothered her, so much so that I didn’t get the interview. This project doesn’t have a goal except to exist.

Whirligig: But it does have an agenda.

Beau: Even agenda sounds pejorative in a way. It has ideas and issues that we speak to, but not one that we make anyone adhere to. You could be with us or not be with us. People will interpret the project, and have, in lots of different ways.

There is going to be an exhibit of all of the artists’ books at the Rochester Public Library in June. They decided to focus on censorship. That’s part of our project. It’s not the main part of the project. The logo they’re using is something like al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here: Begin the Conversation. They want that as an aspect.

I never tell people what they must do. When I am in first contact with an exhibitor I tell them what we hope they will do. I try to let them know what the project is and what we are trying to address. I let them know this is not an art project because that is often what they want. Or they start off wanting this to be a memorial project.

As soon as things get put at a safe distance you know you’re in trouble right away. Al-Mutanabbi Street is as present to us as any street. We are not talking about a labor strike from 1934 that we are all doing work in honor of people who put themselves on the line.

There’s definite things that I’ve come to realize in organizing a project like this. There are stratagems that arts organizations use to keep you at arms length. They often want to defuse potential things that they think might happen. We’ve lost two shows. One in the Netherlands where they wanted to put the equivalent of disclaimers on the exhibit cases. They wanted to have a panel criticizing the project, mostly on the lines of why aren’t there more people from the Middle East in this project? But the reality of this project is that it is more about people in the West being able to see the commonality between al-Mutanabbi Street and their own streets. If this was only a project that was made up only of people from the Middle East and North Africa, artists and writers, and it only contained them, it would be one more case of people in the West going to an exhibit and looking at the work of the other. That’s not what this is about. That exhibit never happened.

Then we lost the exhibit in Los Angeles. The director there wrote me, and it’s always someone on the board, even though the director is fine with it. She wrote me and said somebody on the board felt there wasn’t enough art in the artists’ books. If you look at the artists’ books that’s kind of hard to believe. I wrote her back and I said, “If the museum wants to cancel the exhibit you have to write me a better note, because this isn’t good enough.” A week later she wrote me another note that said the real reason is funding. That’s always a good one.

Whirligig: Because it doesn’t really cost much, does it?

Beau: Right. We charge no fee. We ride whatever insurance they have. We ship the stuff to them. We often have people in the area who could work as volunteers and install. The only thing we ask is that they ship the work on to the next venue or back to me here. But somebody got nervous about it.

Whirligig: One of those things that happens in some institutions like that is they have a concern if there is a big donor that might be offended and then their funding gets cut. They don’t want to lose their money.

Beau: Here’s a story. A couple years ago I had a coordinator at one of our reading series at the bookstore who was a Stegner Fellow in poetry. He coordinated for about a year and we had a lot of poets who were Stegner fellowship poets come up and read at the store. It was really great–a lot of good poets. I asked him as we were approaching March 5th one year how about if we had a reading at Stanford. He said, “Let me post it to some of our professors.” He did and they said yes. It went up the chain until it got to the administration and they said No. This isn’t going to happen. They said that the reading might possibly offend a future donor. Not even a donor that they had.

Whirligig: That’s scary.

Beau: It is scary.

Whirligig: How did you come to own a bookstore and what is that like?

Beau: I’m a poet and a poet has to have a day job.

The Water

she who

sees

the floorshe is

the one

pretending

to be

aloneshe is

the only

eyewitness

to her

childhoodshe wants

to restto notice

herself

in bed

to cover

herself

with the

thin

early lightthat has

pushed

its way

into

the kitchen

What is it like to have a book store? It’s a struggle, a constant struggle. Your emotional life rides along with how much you took in the day before. So a good day you are wildly optimistic and a bad day you’re depressed. It wasn’t that way before the Internet.

Whirligig: Do you have a favorite bookstore story?

Beau: So many. Those stories happen quite frequently. It is the essence of human interaction. Essentially a bookseller is like a dry bartender. People will pour out their life stories to you. The way that they engage that is through the book that they are buying. You make a comment and they make a reply. You make another comment. . . You have the power to be able to say without saying it, tell me about your life, tell me why this book is important to you. What other books do you like? Why are you here and not there? People will just stand there and tell you in a fairly concise way. It’s a wonderful part of being a bookseller.

Here is one of my favorite bookstore stories. It just floated up. We had a store in Sausalito for a couple years and there was a guy who made his living making musical instruments. He would come in and see what new books we might have gotten, anything concerning making musical instruments. He made guitars and other things. I was looking at a book on bullfighting. I had it open on the counter. He looked over and said, “I fought in that ring.” I said, “What?” He said, “Yeah, I was a bullfighter.” So half challenging him I said “bring me in a picture of you and your suit of lights and I’ll put it up.” He came back the next day with a picture. He was in a suit of lights, in a ring. He was looking across, obviously looking at the bull just coming in, and sizing it up. It was a great photo. The look in his eyes–intense, concentrated. He fought in Mexico. He fought in Spain. He told me some stories about that. I asked him what he had done before that. Well, in still another lifetime he had been a marine in the Korean War and was part of the famous retreat of the marines from the Chosin Reservoir in winter. They were fighting a much superior force of Chinese who were pushing them back, and they survived. The people that made it back in the dead of winter. He had gone through all of that to deciding what to do next. . . I’ll be a bullfighter.

You have to love that. That is typical of the kind of story that can emerge in a bookstore where somebody just starts talking about a particular part of their life. We’re all enriched by the stories that people tell us. If you are a writer or an artist you often have friends who are writers or artists. If you’re a young poet and you break up with somebody, you will always have a friend who will say, “You’ll get a great poem out of that.” My response was always to say, “There are the poems you write and the poems you live.” That can be the same for stories. Some people hear a story and can incorporate it into their work directly. For other people that can become a kind of interior part of the scaffolding that makes up their own imagination. They are wonderful. I love storytelling and have always been a storyteller.

Whirligig: What or who are you currently reading?

Beau: I’m about to start Sinan Antoon’s novel called The Corpse Washer set in Iraq.

I often look at books of poetry as they are coming across the counter and read one or two poems. We have an infrequent poetry series at the store and I usually stay so I hear a lot of contemporary poetry. I tend to read the same people that have always inspired me. Though I’ve met a lot of poets through the project and I’ve certainly read a lot more Middle Eastern and Arab American poets since the project started, many of whom I greatly admire.

You know I don’t make any money from the project, but I’ve been rewarded by friendships and being able to read the work of people I’ve come to know and that’s been a tremendous payback.

Whirligig: A project I suspect, that’s taking a full time job worth of hours every week, if not more.

Beau: So many emails that I have to write to people for various reasons. I get up early and then try to put in some time just writing people back, trying to stay abreast, exhibits opening. . . somebody has a question . . .

Whirligig: What advice do you have for those new to poetry reading?

Beau: Don’t read poetry to understand it. Read poetry in the same way that you listen to music. Try to absorbed the poem. Try to let the poem settle on you. Read it once. Try to find the music in it and where it touches your own life. Then you can read it with more specificity later if you want to, or you could just leave it at that reading. Don’t try to walk away from poems with meaning. Try to walk away from poems with pleasure.

Whirligig: and advice to people who are new to poetry writing?

Beau: I would say it’s both the easiest and the hardest thing you’ll ever do. I would say, don’t fool yourself. I would say, find one person who will be your most honest listener to your poem, because if you get to the point that you can write, and you know you can write, and you have someone who really listens to your poem, you will know immediately when you have read a bad line. You can get technically good enough to write a line, and somebody else can say “oh that sounds good,” but when you have someone who can really listen to your poem, they don’t even have to say anything when you get to that that line. It will ring so incredibly false that you’ll have to go back and change it. It’s an interesting process.

Whirligig: Do you mean not even from looking at them but from your own speaking it to them?

Beau: Yes. You couldn’t do that if they weren’t there. You couldn’t have that feeling.

Whirligig: So it’s the witness.

Beau: It is the witness exactly. You need a witness to the poem.

Whirligig: In this life what is most important?

Beau: I think what’s most important in this life is those you love. As a poet, being truthful to what I write.

Whirligig: Is there anything you would like people to know?

Beau: When we had the exhibit in Boston I spoke to a lot of people in a lot of different situations. I began to feel that it was the 1930s and I was a labor organizer. I could practically get up on the table. I’ve done the work on this project long enough so that I can talk extemporaneously about it. I don’t need notes or anything else. It’s almost a stump speech. So one of the things that interests me is finding new words, a new way to describe the project.

In the project email I sent this morning I was apologetic in a sense because I said as a poet this is how it write, this is how I think. I don’t think in real concrete ways, that this is what I’d like you to do. I speak more to the heart and the reasons why somebody should do something. That’s just who I am. Sometimes I have to be real specific. I have to say the work is going to get to you by this date. I ask a lot of people to do things. That has been one of the joys of the project. Finding circles of people who will do things for the project. People will help if they have the time. They will do something. I love those people. They will take the extra step. I keep running into those people and that is really a great feeling to know that there are people out there like that.

Four Crossing Dreams

1.

Out by the road

I wave to my daughterWe are both looking back

2.

Twice to the left

was waterAnd I beckoned to it

3.

My son is shaking

twelve dry peppershe is whispering the words

that he needs to suffer4.

I am angry with sudden hope

crossing, Comparative, Your Standards, Water, and Four Crossing Dreams from Ways to Reach the Open Boat, Barley Books.

Lesson from What Happens, Cloud Marauder Press.

All poems copyright and courtesy of Beau Beausoleil.

Barley Books

An Inventory Of Al-Mutanabbi Street, UK site

Al-Muranabbi Street Starts Here