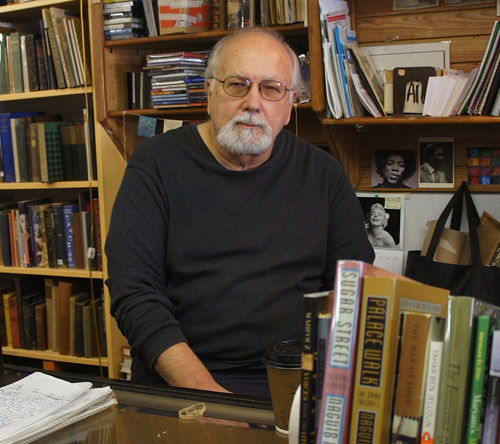

Michelle Wilson is a papermaker in an extremely complex sense. Her work with paper is both conceptual and concrete as it extends from the making of sheets for artist’s books and printmaking to social practice, sculpture and installation. As a somewhat recent transplant to the Bay Area, Wilson has quickly embedded herself and her work into the consciousness of the local art scene with a residency at the School of Visual Philosophy, a Small Plates commission from San Francisco Center for the Book, teaching at both San José State and Stanford, engagement with a handful of arts organizations, and many exhibitions.

This summer, Wilson’s collaboration with Anne Beck, The Rhinoceros Project, travels to the Salina Art Center (Salina, Kansas), Shotwell Paper Mill (San Francisco, California), the Healdsburg Center for the Arts (Healdsburg, California), and later this fall to the Janet Turner Print Museum in Chico, California. Her work is included in The Power of the Page: Artist Books as Agents for Change at the New Museum of Los Gatos (NUMU in Los Gatos, California), and Pulp as Portal, Socially Engaged Hand Papermaking at the Salina Art Center in Salina, KS. Wilson has a BFA from Moore College of Art and Design, and an MFA from the University of the Arts, both in Philadelphia.

We got together on a lovely spring afternoon towards the end of the semester to talk about art and teaching.

Nanette: I first became acquainted with your work in 2010 at an SGCI Conference in Philadelphia, occurring at the same time as Philagrafika, where I came upon a Book Bomb intervention in a public park. How did this collaboration with Mary Tasillo come about?

Michelle: Book Bombs began as a question I posed on Facebook. I was reading about yarn bombing, the tradition of knitting or crocheting something that is then bombed— left in a public space—a form of craft meets street art. I’m not a knitter or a crocheter; I’m a book artist, and so I posted a status update, “What would it mean to book bomb?” Mary took me seriously, and through our conversation, we discussed where people read in public space, who owns public space, and it led us to the idea of park benches. In Philly, every park bench has this center bar installed that is called the “arm rest,” but is designed to prevent a homeless person from sleeping comfortably on a bench. This seemed like an ideal place to install a book. Our project grew from this initial idea. And thus, Book Bombs was born.

Nanette: What were you envisioning regarding the scope and effects of Book Bombs?

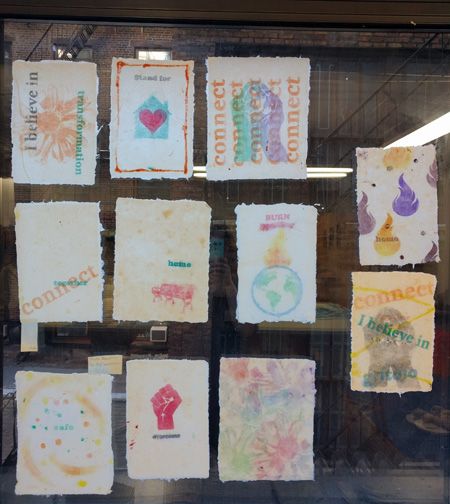

Michelle: We originally saw Book Bombs as just a project for Philagrafika 2010. However, we’ve had so much fun, we’ve continued. It’s been tricky to keep it up transcontinentally, but we manage. Most recently, we did a sort of intervention-workshop at the Center for Book Arts in New York called Keeping the Fire Alive. This was designed as a workshop for activists who were interested in using papermaking in their work, as well using it as a form of self-care against fatigue and for continued resistance. We’d originally proposed the workshop during the summer of 2016, before the election, thinking it would be a very different conversation.

Nanette: How is papermaking used for self-care?