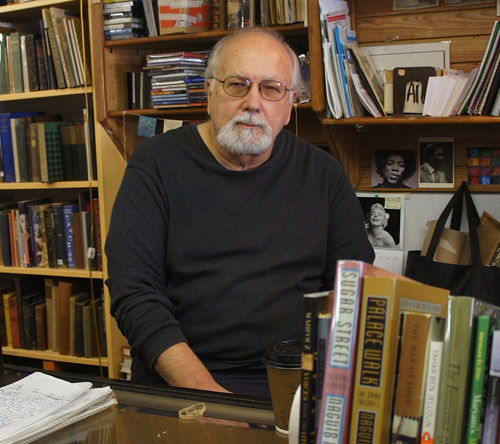

Beau Beausoleil is a San Francisco-based poet and the proprietor of the Great Overland Book Company, which is located in San Francisco’s Inner Sunset neighborhood. Beausoleil has written more than ten books of poetry. His most recent collection, Ways to Reach the Open Boat, was published by Barley Books, UK in 2013.

In 2007 Beausoleil read an article in The New York Times about a car bombing on al-Mutanabbi Street, the historic bookseller’s street in Bagdad. This incident inspired the creation of the al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition, a project which currently has five distinct components: 130 letterpress printed broadsides; 260 artists’ books; a publication of poetry and prose titled Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here; the coordination of poetry readings around the world each year on the March 5th anniversary of the bombing; and most recently Absence and Presence, a call to 260 printmakers for the creation of fine art prints.

The project involves hundreds of artists who have created work specifically as a response to the 2007 bombing; and extensive local and international exhibition schedules, much of which Beausoleil coordinates himself. Complete editions of the visual art responses will ultimately be donated to the Iraqi National Library in Bagdad.

We met in early February over a cup of tea at Beau’s kitchen table.

Whirligig: What is poetry?

Beau: What is poetry? At one point in my life I stood on the corner of Powell and Geary, it was real close to Union Square not that far from Macy’s, and I had a little box next to me on the ground that had a sign that read “Support your local poet.” I would give out multiple copies of a poem that I had printed out to anyone who would take them. They didn’t know that they were poetry. My secret hope was that some patron would appear out of nowhere with a wallet, but of course that never happened.

I usually made enough to print out the next batch of poems. Some people would avoid me. They would go out into the street thinking that I was handing out a religious tract or a political tract of one kind or another. Some people would take them. I’d see them read them. I’d see them crumple them up after half a block and throw them away. But every now and then something would happen. I remember this one guy who took a poem. I watched him walk down Powell and I could see that he was reading the poem. He got about three quarters down the block. He turned around and walked back to me and said in this agitated voice, “I don’t know what this means, but this one line, that speaks to my life.” That’s poetry.

One time I was part of a group that was visiting Folsom Prison where there was a writer’s workshop. The visitors would read and then the prisoners would read. During the break this guy came up to me and said, “Are you Beau Beausoleil?” And I said, “Yes.” He said, “Did you have a poem in . . .” and he named this small magazine, and I said, “Yes.” He said. “Did it go like this. . .” and he recited my poem back to me. I was pretty stunned. He said, “I just wanted to tell you that that is the poem that started me writing.” That’s poetry.

Lorca, the Spanish poet, tells a story about duende. Duende is the inexpressible in art, in beauty. It’s there and you can feel it. Some people can recognize it. It’s an important part of the life of any artist who is really at that point. He tells a story to illustrate it.

There was a flamenco contest in this basement in Spain. All these young women are assembled. They are all in their 20s and beautiful. They are getting ready to go on the stage to perform before these three judges. Suddenly the door opens. A woman in her late 50s walks in, walks straight up to the stage, throws her arms in the air and the judges declare the contest over because they could see that she had duende. That’s poetry.

Poetry is something that gives you back part of your own life. It allows you to see your own life in another form, another way. That’s what poetry is.