A Conversation with Macy Chadwick

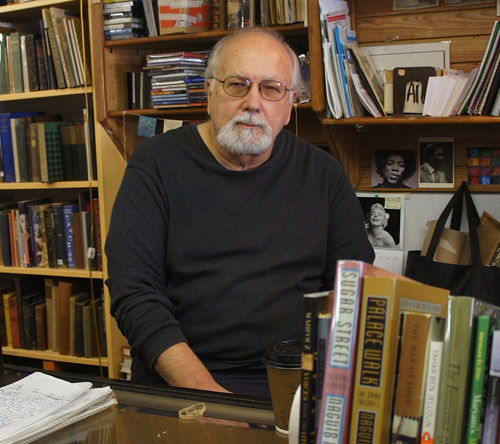

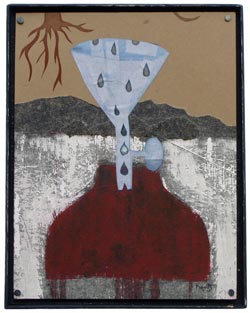

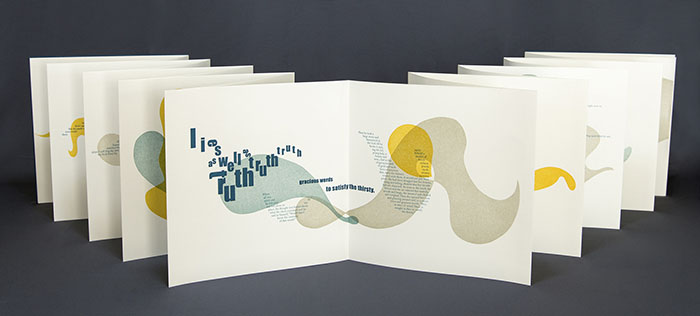

Macy Chadwick is the founder and director of In Cahoots Residency in Petaluma, California. Macy is remarkable as a creative residency host in part because she is exceptionally personable with a wonderful gift of giving a story, often with unpredictable humor and resulting laughter. Her own work as a printmaker and book artist is visually poetic and imbued with a sensitive essence of personal reflection. We talked about her work and the running of In Cahoots while sitting under a large oak tree on the residency grounds.

Nanette: How did you come to art?

Macy: When I was little, I loved all kinds of art, and my mom really encouraged it. I took some after school art classes starting in third grade and continued with that until high school. In order to take the advanced art classes in high school, I had to commit to being an art major in college because the goal of the advanced art classes was to help you prepare a portfolio to apply to college. So I said, yeah, I’ll be an art major in college. Then I decided I really did want to do that. I pursued my BFA, but I was never one of the artsy kids. I didn’t have purple hair or tattoos, still don’t. But I was definitely one of the creative kids, and art has always been a big part of my life.

Nanette: How did you get into printmaking and book arts?

Macy: In undergrad, I was an Illustration major and I never really loved it. I had loved drawing in high school, because that was just what we were offered. In college, I started taking printmaking classes to do my illustrations and then I realized I was actually more interested in making prints about my own ideas and concepts than I was in illustrating other people’s ideas. So, I ended up being a double major in Illustration and Printmaking.

This was at Washington University in St. Louis. I was very interested in putting my prints into a sequence. At the time, they didn’t have book arts there, so I went to the library and checked out the Japanese Stab Binding book—the one with the green cover. I don’t know why, but that’s the only book on book arts techniques that every library seems to have. So, I learned stab binding, and I taught myself a couple of other bindings in undergrad.

Between undergrad and grad school, I took Book Arts classes at Oregon College of Art and Craft with Barb Tetenbaum. It was from Barb that I learned the foundation of everything I know about book arts and letterpress printing. I’ve learned more over the years, but Barb taught me so much. As happens with your first teacher—you still reference what they taught you, and who they admired. Barb admired Tim Barrett, Hedi Kyle, Patty Scobey, Julie Chen, and Gary Frost. So, I still admire all those people, and others, too. I continued to study Book Arts and Printmaking in grad school and then I learned more when I moved to Berkeley to work for Julie Chen.

Nanette: When was that?

Macy: I moved to Berkeley in 2003. I had graduated from Wash U in 1994. The rest of the nineties I lived in Portland, Oregon. I studied with Barb at the Oregon College of Art and Craft, which has since closed. Then I went to grad school at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, from 2001 to 2003. UArts closed recently as well.