A Conversation with printmaker Rebecca Gilbert

Rebecca Gilbert is a printmaker’s printmaker—impressively knowledgeable about printmaking history, and historical and contemporary print processes. Rebecca astounds with her joyful commitment to a seven year long project based on Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death. Rebecca’s own dance demonstrates an insightful perception of humanity delivered with generosity, depth, and a fresh lightness of the creative spirit.

This conversation took place under a large oak tree during a summer printmaking residency at In Cahoots Residency in Petaluma, California.

Nanette: How did you come to art?

Rebecca: I pretty much always wanted to be an artist. Since elementary school at least. And I was actually just thinking about this the other day. I met my best friend in elementary school, Bobby Riefsnyder, on the first day of kindergarten. We would play together every day after school. I would pretend that I was an art teacher and he would pretend to be a music teacher. We probably played that every day for a couple of years, and it never got old, so I feel like I always knew I wanted to be an artist and I always knew I wanted also to be an educator. Even then, I thought of those as two different things that you could merge into one, and they are two totally different sets of skills. When I went to college, I started as an art education major, because that seemed like the most obvious way to pursue both. I don’t know what art education programs are like now, but at that time, I found that learning about art and making art weren’t very important in that major. All of the focus was on teaching, and art barely even felt secondary, so I changed my major to printmaking.

Nanette: As an undergrad?

Rebecca: As an undergrad, yes.

Nanette: And why printmaking? They actually had a printmaking major?

Rebecca: Yes. I made my first print in high school. It was a monotype. I was thinking about this recently, too. I forgot that monotype is what made me fall in love with printmaking. I was hooked after the very first one, and I very rarely make monotypes these days. My high school had one little press that they would wheel out of the closet every now and then so we could make some prints, and I loved it.

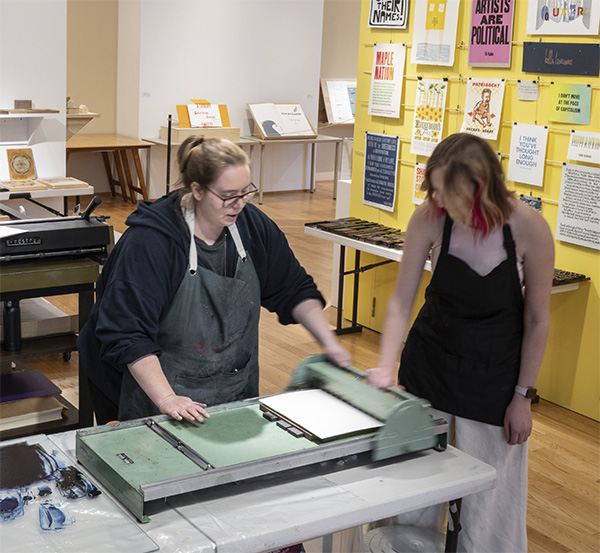

In college, I had taken a bunch of printmaking classes, even as an education major. Besides the process involved in making a print, I just love all the tools and gadgets and presses, and all the printmakers seemed a little dangerous, edgy.

Nanette: More edgy than the other artists?

Rebecca: Yeah, yeah. [laughs]

That was part of what initially drew me to it. There’s such a long list of everything that I love about printmaking that keeps me drawn to it now.

Nanette: So, you were a printmaker right off the bat?