A Conversation with printmaker Rebecca Gilbert

Rebecca Gilbert is a printmaker’s printmaker—impressively knowledgeable about printmaking history, and historical and contemporary print processes. Rebecca astounds with her joyful commitment to a seven year long project based on Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death. Rebecca’s own dance demonstrates an insightful perception of humanity delivered with generosity, depth, and a fresh lightness of the creative spirit.

This conversation took place under a large oak tree during a summer printmaking residency at In Cahoots Residency in Petaluma, California.

Nanette: How did you come to art?

Rebecca: I pretty much always wanted to be an artist. Since elementary school at least. And I was actually just thinking about this the other day. I met my best friend in elementary school, Bobby Riefsnyder, on the first day of kindergarten. We would play together every day after school. I would pretend that I was an art teacher and he would pretend to be a music teacher. We probably played that every day for a couple of years, and it never got old, so I feel like I always knew I wanted to be an artist and I always knew I wanted also to be an educator. Even then, I thought of those as two different things that you could merge into one, and they are two totally different sets of skills. When I went to college, I started as an art education major, because that seemed like the most obvious way to pursue both. I don’t know what art education programs are like now, but at that time, I found that learning about art and making art weren’t very important in that major. All of the focus was on teaching, and art barely even felt secondary, so I changed my major to printmaking.

Nanette: As an undergrad?

Rebecca: As an undergrad, yes.

Nanette: And why printmaking? They actually had a printmaking major?

Rebecca: Yes. I made my first print in high school. It was a monotype. I was thinking about this recently, too. I forgot that monotype is what made me fall in love with printmaking. I was hooked after the very first one, and I very rarely make monotypes these days. My high school had one little press that they would wheel out of the closet every now and then so we could make some prints, and I loved it.

In college, I had taken a bunch of printmaking classes, even as an education major. Besides the process involved in making a print, I just love all the tools and gadgets and presses, and all the printmakers seemed a little dangerous, edgy.

Nanette: More edgy than the other artists?

Rebecca: Yeah, yeah. [laughs]

That was part of what initially drew me to it. There’s such a long list of everything that I love about printmaking that keeps me drawn to it now.

Nanette: So, you were a printmaker right off the bat?

Rebecca: Yes.

Nanette: And then you went to grad school for printmaking, too?

Rebecca: Yes. By the time I finished undergrad, I was 25 years old, in part because I didn’t have an academic advisor, and in part because I changed my major from Art Ed to Printmaking. I also had to work all the way through college to support myself. I did go straight to grad school. I knew that I loved printmaking so much that I wanted to continue that. But, as a 25 year old with a BFA in Printmaking, I thought I knew everything. [laughs] So when I was looking for graduate programs for printmaking, I was looking for something that was printmaking and something else.

I applied to a whole bunch of graduate programs. One of the ones that accepted me was The University of Arts in Philadelphia. They offered an MFA in Printmaking & Book Arts combined. I love books through and through, so it seemed perfect because I got to study bookmaking and book arts and continue with a focus on printmaking. Of course it only took about a week of grad school to realize there was still a whole lot left to learn about printmaking. You know grad school is good at checking you and putting you back in your place really quick, which is great. And, of course, the more you learn about something, the more you realize you don’t know. And here I am all these years later and still learning new things all the time.

Nanette: That’s a good sign.

Rebecca: It is. It’s cool.

Nanette: So you make books, too?

Rebecca: Yes. Not as much as prints and print-based sculptures and objects. Books and bookmaking are an important part of my life, and very directly affect the way I think about making art and images and presenting art and images. But it’s rare that I would make a formal artist book.

Studying printmaking and book arts, I learned to make a lot of book structures and really think about paper, narrative and storytelling, sequence, and all of these valuable things about communication, materials, and construction that I feel directly affects everything I make. Also, since I went to school for printmaking and book arts, I got to do several hands-on book conservation internships where I got to repair historic books and works on paper. Oddly, that led to working with fossils and historic natural history specimens and even insect conservation. Again, the preciousness of history, working with historic objects, materials, bindings, and methods of traditional printmaking also inform my content, my method of research and my method and format for making art too.

That said, I am currently working on something that could maybe be considered like an artist book in many ways.

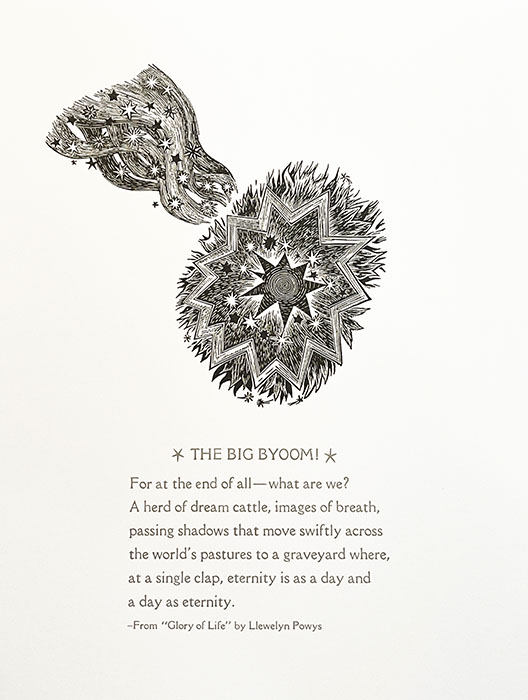

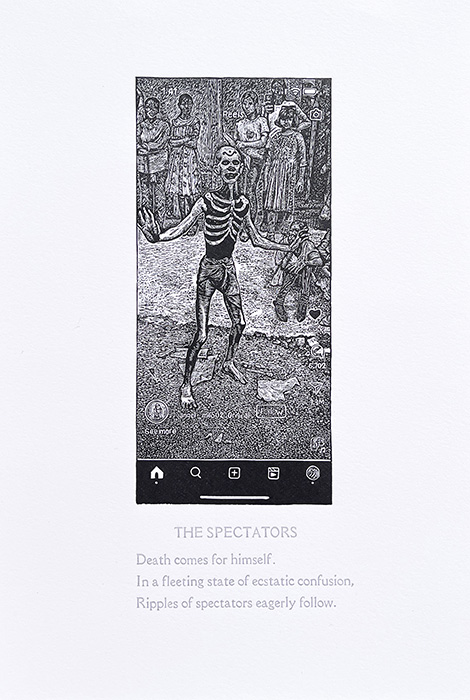

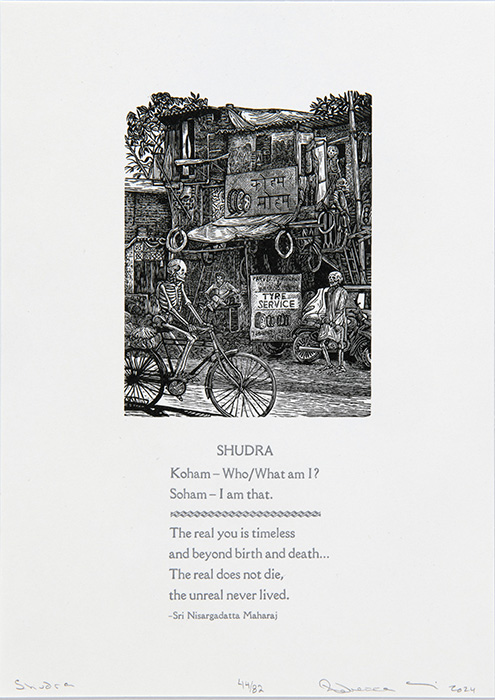

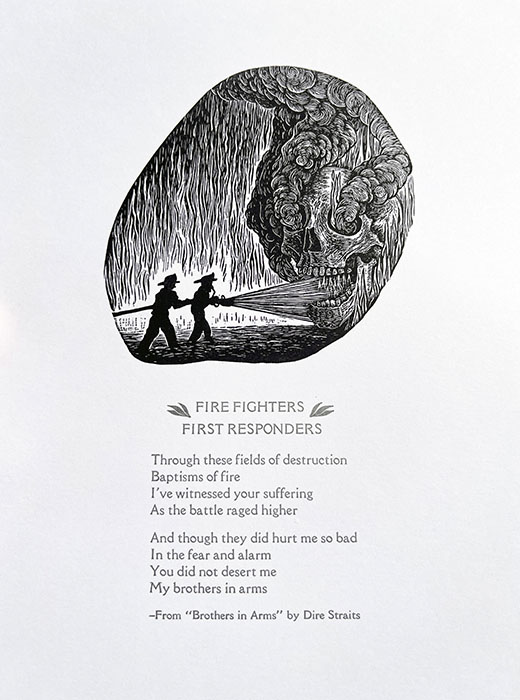

It’s my Dance of Death in Two Parts. It’s a project that I’ve been working on for about six years now. I already completed more than three-fourths of the project. The first half of the project, Part One, was to remake all 41 of Hans Holbein the Younger’s Dance of Death series that was published in 1538. That involved redrawing, engraving, and printing all 41 blocks and printing them with movable type that I also set by hand. For Part Two of the project, I’m matching my recreations of Holbein’s prints with 41 additional Dance of Death prints using my own drawings and curating and even sometimes writing my own text. The project will culminate into a series of 82 Dance of Death Prints. I’m making some available for sale individually, but half of the prints from each edition will be collated into complete boxed sets. I don’t mind saying that the cloth covered clamshell boxes that I’m building to house the prints are stunning. They have two compartments in them and a wood engraving on the cover, so it is very much like an unbound book and could be considered an artist’s book, I suppose. Or it could just be considered a set of prints in a box.

Nanette: How did you come to the Hans Holbein Dance of Death series?

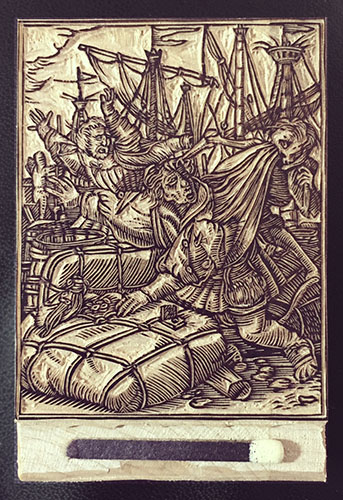

Rebecca: I teach printmaking in college, and whenever I start teaching a new family of printmaking, I usually give a presentation on the history of the process. When I talk about the history of relief printmaking, I always include an image from Holbein’s Dance of Death series, in part because I just like the imagery. I mean, they look cool, you know, these dancing skeletons. I include it because I like it, but moreover, I include it because it is a really good time in my talk to stop and talk about the division of labor that has existed throughout the history of printmaking, and often still exists today. In the 1500s, it was pretty normal that one person would be the artist, that was Hans Holbein. He made all of the drawings. A block carver named Hans Lützelburger was actually the person that carved all of these miniature blocks. I should stop here to mention these blocks are smaller than two by three inches. A third group of printers printed the series, and it’s very likely that a different set of folks did all of the binding.

Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death is, I think, the most well-known of this theme that has been revisited by artists over and over through the centuries. One reason is the breadth, the impressive number of images in the series. Another reason is simply that the drawings are really incredible. A third reason is the impressiveness of the miniature scale. It takes a tremendous amount of skill and focus to be able to engrave an image so small, and here with Holbein and Lützelburger’s project you have 41! In mine, 82! I’m glad that Hans Lützelburger, the block cutter, gets his due credit because oftentimes a block cutter wouldn’t. And perhaps that’s because it was actually Lützelburger that commissioned Holbein to make the drawings, rather than Holbein making the drawings and commissioning Lützelburger to carve them. It was Lützelburger’s project.

Nanette: But we think of them as Holbein’s work?

Rebecca: Yes, but it was more of a collaboration. I don’t mean to take away from the credit due Holbein. But it was more of a collaboration.

So there’s the artist, the block cutter, and then, you know, sometimes even a third person does the printing and a fourth person does the binding. I would look at this year after year, semester after semester, talking to my students. And every time I would think, oh, I wish I was Hans Lützelburger. I wish I was the one that got to carve these drawings. One day I was talking to my husband, Naren, and I was like, you know, nothing is stopping me. I can do it if I want. And because Lützelburger didn’t even do the drawings, I would be doing what Lützelburger did. I really felt like I was communing with Holbein and Lützelburger all these years while I was staring through magnification engraving these images.

Nanette: Because you did exact copies?

Rebecca: Yes.

Nanette: At the same scale?

Rebecca: Yes.

Nanette: It’s not like you had those original blocks that you could print.

Rebecca: Right. Though I will say, at least Lützelburger had the drawings on the blocks, because I had to get the drawings on the blocks, too, which took a long time. [laughs] It was excruciating and hard.

So, I’m standing in my living room talking to Naren (my husband). I’ll never forget this moment. Where we were standing. I was like, I’m going to do it. I’m going to remake all 41. And then in the very next instant, I realized that if it was going to be a relevant and worthwhile project, I had to match those 41 Holbein images with 41 of my own drawings and prints. So within about a minute, I went from not having the project to having this enormous project. I got started later that day and I have worked on it almost every single day since I started.

Nanette: Wow. Almost six years now. How many years do you project out to complete?

Rebecca: I think I have a little bit over a year’s worth of work left.

I’m not making the work for an exhibit. I’m making the work to make the work, but I do have an exhibit lined up at the Print Center in Philadelphia in 2027.

It wouldn’t even be an option to rush the project if I wanted to, because everything about the process of making it is so naturally slow and demands a lot of time.

Just for clarification, Holbein and Lützelburger’s blocks were wood cuts and mine are wood engraving. The difference is plank grain and end grain, and the carving tools. Woodcut is carved into plank grain wood, and because it’s plank grain wood, you’re using gouges and knives. For wood engraving, you’re using a hardwood. You typically don’t use a hardwood for wood cut. You use more of a medium hardness of wood. For wood engraving, you’re using an end grain hardwood.

Nanette: Is this how you came to wood engraving?

Rebecca: It was the influence of book conservation and the history of traditional printmaking that brought wood engraving to me. I was working at a Rare Books Library in a Natural History Museum called the Wagner Free Institute of Science. I worked there for 11 years. A lot of the collection featured wood engraved illustrations, and I would spend hours with these books every day intimately looking through all the images.

At this point, I had an MFA in printmaking and years of printmaking experience under my belt, but I had never met a wood engraver or anyone that even talked about wood engraving. So I’m looking at these illustrations and it’s saying next to it that it’s an engraving and I’m like, I know what an engraving is. It’s not that.

It took a while to find someone that taught wood engraving. I ended up finding Jim Horton, who’s a master wood engraver. He lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He was teaching a week-long workshop at Augusta Heritage Center in West Virginia. I took my husband with me and we went to West Virginia, and I took this week-long wood engraving workshop. Everything just clicked immediately because up to that point, I really focused on woodcut and etching and dry point. I feel like in some ways, wood engraving is a marriage of that because you have the relief process of carving into wood, but that fine line work of etching. Of course, it’s a white line instead of a black line that you’re carving. And I love it. I’m hooked. I think it’s pretty obvious.

Nanette: So wood engraving is your focus now.

Rebecca: Yeah, well, I still do a lot of larger scale color woodcut. I haven’t been sharing that as much lately. And I will admit this Dance of Death project is the most important thing in my whole life because the point of it is to memorialize my husband Naren and our love by getting it into as many library and museum collections as possible. There will be a dedication page and it’s all dedicated to Naren. I’m so glad he was here when I started the project. I didn’t mention for the interview that he died very shortly after I started the project. But in addition to the dedication page, he actually posed for the project when he was still here. And I’ll say, a lot of people ask how I’m able to stick with a project this big for so long. It’s easy to stick with it because Naren was here when I started it. He was really excited about the project, and when he posed for one of the prints, he was really excited to be included. He was a rare book dealer and an editor and a whole bunch of wonderful things. But he also did some online gaming, and that is how he is depicted in the series. He was happy that he was included and that gaming was also included. So it’s really easy to stick with the project, because it’s all for him. And I’ll just tell you this project really helped me through very, very, very dark days. It has given me purpose, and it gave me something to focus on and something to sit with during lockdown and extreme grief.

The dedication page is for Naren. His visual likeness is in there. A few of his poems are also included as texts that accompany some of the images. There’s an image of me as the printmaker that includes one of his poems. And then there is another image that is the Caregiver/Caretaker/Master Gardener, that is also printed with one of his poems.

There’s another print I made, just a year or two ago that includes a poem written by Naren’s best friend, Jim. I’m glad that Jim could be included and I feel like that brings Naren in even more. Naren is in the project through and through, like the lyrics, like the songs that we would sit on the stoop and sing together while we were drinking beers in the evening and things like that.

Nanette: You have about a year left, and you’re into your part of the series, your interpretation. Have all of the drawings been made?

Rebecca: No.

Nanette: It’s really interesting to me that, if it was me and I was working on such a long project, the end look of my prints would be way different than the beginning look of my prints. How is that working out for you?

Rebecca: Well, that is happening a little bit, and I think it’s very cool. One little clarification is that I haven’t been doing the prints in any particular order. Even from the beginning, I was working on Holbein’s and mine at the same time. And I was just choosing images randomly from Holbein, and then, I’d get an idea for one of my own and do that. But then because Naren died, I mean, I won’t even attempt to find words for the devastation, but I was not feeling inspired or creative. I was feeling everything else. So having all of Holbein’s images, I could sit and focus on that and transfer an image and ink it in and engrave, and just pour myself into this intense labor without having to feel creative or artistic. I think for that reason, the first couple of years that I was working on this, I definitely leaned toward doing way more Holbein than doing my own. And then before I knew it, a little over a year ago, I didn’t even realize I was working on the final Holbein and then I realized I had done them all. So it did just kind of end up that way, that I had completed those first.

Recently, I was collating some prints together because I was traveling to teach and give a talk at Frogman’s, and I just wanted to show some prints. I looked at some of the earlier ones, and for a minute I almost felt a little bit embarrassed, because in my view, they’re not as good as how I’m engraving now. But then, luckily, I immediately had the common sense to realize, if I’m engraving for hours every single day for six years and they’re not getting better? That’s when I would be embarrassed. Yeah. There’s nothing embarrassing about getting better at engraving. That is what I want to do. So I actually think that’s pretty cool.

Nanette: Are you thinking about a project beyond?

Rebecca: Oh, yeah. I just have so many ideas and projects, and I’m always working on multiple things at the same time. There aren’t enough hours in the day.

The projects I’m working on in the background are large multi-block reduction color woodcuts of spirits that mostly manifest themselves in the form of fireballs. There are lots of different stories around the globe of spirits manifesting in that way. I’ve gotten to see a few in different places over my lifetime. In a way, depicting the feeling or visual of that is impossible, so I need to figure out why I’m doing it and what I’m trying to do or say with it. In the meantime, I’m just working on a whole bunch of different ways to draw them and print them, and we’ll see where it goes.

I also have a collaborative project queued up with my friend Brien Biedler. He is a tool-maker as well as a very masterful bookbinder and artist. Our plan is to write a story and illustrate, print, and bind it together. I’m really looking forward to working with him more. I know our project is going to be so good!

Nanette: Your left inner arm tattoo looks like a wood engraving. Did you design that?

Rebecca: Only in part. It was a process getting this tattoo. I got it from an artist in Manhattan named Anil Gupta, and he only does custom tattoos. He had tattooed Naren’s forearm years ago. And not only because I am in love with Naren and he’s wonderful, but it’s the most beautiful tattoo I had ever seen in my life. Everyone else that saw it agreed. It was really stunning and delicate. The technique, the image, the meaning, everything was really stunning. Naren and I had always talked about me eventually going and getting a tattoo there. Unfortunately, I didn’t get it until after Naren died.

To get a custom tattoo from Anil Gupta requires writing an essay about why you want a tattoo, what kind of tattoo you think you might want, and then sending a folder of reference material, including images of things that inspire you that you think about. Once I did that, I went and spent an entire day with him in his studio just talking to him and getting to know him. We talked about Naren, what I had written to him, and the images that I had collected. The entire day while we sat and spoke, he drew. And as he was drawing, I said, I like that, and no, I don’t like that. Everything he was drawing was from our conversation. By the very end of the day, he had a sketch. I went back home to Philly and I came back a month later, and he started the tattoo. He tattooed for eight straight hours, but it wasn’t finished. Then I had to go home and let my skin heal for a month and then go back again and get it completed. He did draw it and tattoo it in the style of an engraving, since that’s such an important part of my life. The image is the earth, and you can see North America at the top. Then along the top of the earth is this mountain range, which is actually Naren’s heartbeat. In the middle of the heartbeat is his name in Sanskrit, standing on top of the earth. Then soaring through a night sky over top of the earth toward a giant flaming sun, is a comet with chunks and steam trailing off of it. Originally, we were thinking that Naren was the name and that I was supposed to be the comet. That was Anil Gupta being really supportive of me sitting and crying in his studio and just, you know, trying to empower me. But really, and I think this is okay, I feel more like this is me (and I’m pointing to Naren’s name) because I’m still planted on the earth, and this huge and powerful comet is actually Naren, because he’s free.

Nanette: Wow, it’s really beautiful.

Rebecca: Thank you.

Rebecca Gilbert is a Philadelphia-based artist whose work exemplifies a dedication to traditional printmaking processes. Influenced by years of experience in book arts and rare book conservation, her innovation in executing these processes in combination with cut paper and assemblage, push the boundaries of what a print can be.

Rebecca earned her MFA in Printmaking & Book Arts from The University of the Arts, and her BFA in Printmaking from Marshall University. She has extensive experience teaching printmaking and book arts at numerous institutions of higher education. She is an active member and serves on the board of The Wood Engravers’ Network, a non-profit organization dedicated to the advancement and appreciation of wood engraving, its practice, and its history; and she is represented by The Print Center Gallery in Philadelphia.

Rebecca’s prints can be found in numerous public collections, including the Victoria & Albert Museum, Ashmolean Museum, Gregynog Hall & Library, Zuckerman Museum of Art Archives, St. Bride Foundation, the Free Library of Philadelphia Print and Picture Collection, and Princeton University Library’s Graphic Arts Collection. She maintains an active exhibition record, and has extensively exhibited her work regionally, nationally, and internationally, including in galleries and museums in New York, California, Spain, Canada, Korea, Estonia, France, and England.

Among Rebecca’s most recent awards are an Independence Foundation Grant to support her current project, A Dance of Death in Two Parts; a Victor Hammer Fellowship from Wells College in Aurora, New York; an Illuminate the Arts Grant; a Creative Research and Innovation Grant; and a Winterthur Artist/Maker Fellowship

rebeccaprint.com

@rebecca_print

In Cahoots Residency

This interview was conducted in August 2025 at In Cahoots Residency by Nanette Wylde.