A Conversation with printmaker Sophie Loubere

Sophie Loubere stands out as an artist invested in the conceptual nature of historical imagery while exploring materials and processes. She moves deftly through a range of studio practices — working with wood type on a Vandercook, hand working intaglio plates, exploring natural dyes, papermaking, creating multimedia installations, book arts, and writing. We met during a summertime printmaking residency at In Cahoots Residency in Petaluma, California. Our conversation took place in the etching studio towards the end of our residency.

Nanette: How did you come to art?

Sophie: I started in elementary school, and it was just something that I was good at. I started using chalk pastels, making pastel paintings, getting positive responses, and then I just kept on going. Eventually it was just one of those things where it just felt like it was what I needed to do, which I’m sure a lot of artists can relate to.

Nanette: Did you go to art school right after high school?

Sophie: I went to the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, and I was an art major. But while I was there, I was just feeling like the curriculum wasn’t really serving my needs, so I wound up transferring to Rhode Island School of Design in their illustration program.

I’ve always been interested in words and books and writing . So for a while, I thought that I would potentially become an illustrator. But then my interests just wound up being a little too noncommercial, a little too artsy fartsy, more interested in material, more interested in concept, and making artist books as opposed to illustrations for editorial and things like that.

When I went into the illustration program, I didn’t fully understand that the conventional commercial way of making money doing illustration would be to make illustrations for editorial magazines or for working in animation and designing characters for game studios and things like that.That just was not really where my interests lay. Then one winter session, I wound up taking a printmaking course, Painterly Prints, and I learned aquatint and monoprinting.

After that I was really into etching. I spent my senior year mostly doing etching projects working on this extended sort of book project. After I graduated, I set up my own studio in Seattle. I was working as a graphic designer and publications manager at a nonprofit art school. I had a little studio and I wound up getting some grant money so I was able to get a little press. Then I basically just explored varieties of ways of doing printmaking. I was feeling a little bit frustrated because I didn’t have a conventional printmaking background because I hadn’t majored in it when I was an undergrad. I was trying to learn from books, YouTube videos. I taught myself how to mezzotint, and eventually I just felt like I needed some more specific background. I applied for grad school. I got into a grad school that had a pretty in-depth printmaking program and that’s where I honed both my practice as well as my printmaking skills.

Nanette: So you’re primarily a printmaker?

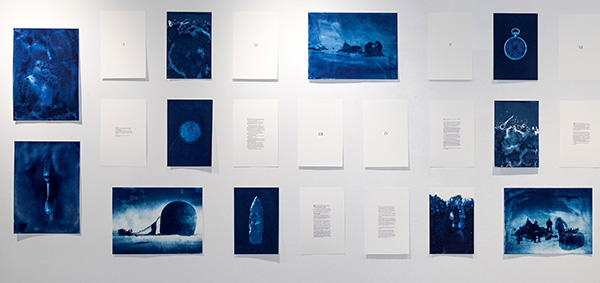

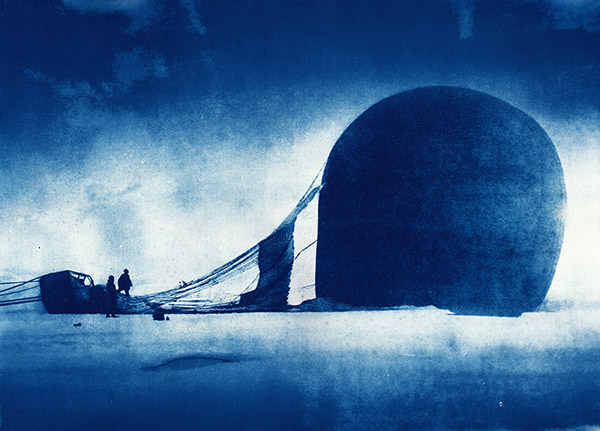

Sophie: At this point, yes. I’m open to making in pretty much any particular way. I have worked with fabrics before. I’ve done installation. I’ve done audio and video work to go along with the prints. But I think that primarily when I’m thinking conceptually, the majority of the time it winds up being a print in some way or other, and print doesn’t necessarily mean something that is like a letterpress print. I also have done things working with cyanotypes and alternative photography. I view those things as prints as well.

In my view, there’s a lot of different meshing that goes on between all these different artistic media. I would say that printmaking falls into a lot of different categories.

Nanette: Are you still making books?