Angelica Muro is an integrated artist, curator, and art educator with a strong interest in cultural criticism. Originally from the Central Valley agricultural community of Hopeton, California, Muro grew up on an apple orchard. As a child she became interested in photography, media imagery and popular culture. Muro served as Gallery Coordinator for WORKS/San José for five years, and as Educational Programmer for Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana (MACLA, San José, California) for three years. She has a B.A. in photography from San José State University, and an MFA from Mills College in Oakland, California. She is currently Director and Chair of Visual and Public Art at California State University, Monterey where she teaches courses in photography, integrated media and media culture.

Angelica Muro is an integrated artist, curator, and art educator with a strong interest in cultural criticism. Originally from the Central Valley agricultural community of Hopeton, California, Muro grew up on an apple orchard. As a child she became interested in photography, media imagery and popular culture. Muro served as Gallery Coordinator for WORKS/San José for five years, and as Educational Programmer for Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana (MACLA, San José, California) for three years. She has a B.A. in photography from San José State University, and an MFA from Mills College in Oakland, California. She is currently Director and Chair of Visual and Public Art at California State University, Monterey where she teaches courses in photography, integrated media and media culture.

Her newest project, created with Juan Luna-Avin, Club Lido: Wild Eyes & Occasional Dreams opened February 12 at Empire Seven Studios in San José. We chatted over tea in early January, at Angelica’s Japantown (San José) bungalow. Reina Sofía, Angelica’s eight-year-old rescue pup, sat on her lap.

Whirligig: How did you come to be an artist?

Angelica: I’ve been interested in art since I was a child, but I was never really good at making—I suppose my vision never matched my actual skill set, it still doesn’t. I remember always trying to make things such as sculptures and drawings, but never having the dexterity. Photography came into my life very early—my fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Dixon, had a pile of National Geographic magazines I was pointed to whenever I finished my assignment early—this was the first time I was truly able to look at images, photographs, people. Since then, it’s become my primary area of interest, socially and culturally.

Whirligig: The first time you were able to look at images or that you became aware of the power of images?

Angelica: Aware of the power, of ways of seeing, of actually looking. We are so visually saturated, so much so that we are not actually seeing. I read recently that the brain is on a need-to-know basis. Our brains store the information in our environment and we don’t actually see it, even as we know it is there.

I very vividly remember looking through these National Geographics and seeing, seeing things that I had never seen before. It was new information. This is why travel is so exciting, it’s overwhelming new information for us that we are absorbing in a completely different way, and we take that absorption as being creative influences.

Whirligig: Much of your work exploits and reveals the tensions between consumer celebrity culture and the realities of working class and immigrant lives in contemporary America, perhaps even specifically California. Who do you see as your audience for this work and what do you hope it achieves?

Angelica: I don’t often think about audience in the traditional sense; although as an educator, I often address ethical concerns involving audience with my students. I happen to live and work in California, so my work deals with the complexities of this eco-system—the spectrum of productivity, exploitation, and the distribution of wealth—and often explores issues of gender, race, and class. I’m interested in social issues, and I find that visual tension inspires me to create.

I think there’s several ways to think about audience—I remember being in graduate school, a time that allowed me to experiment with ideas with a critical, yet limited audience. Suddenly, I had a body of work about being Latina, being a woman, being the daughter of a farmworker, and navigating social constructs. And then my audience became people who where interested in issues of identity. However, my work deals with larger social issues of equalization, socialization, conditioning, and the various codes of gender identification. It’s a dialogue with my community, my artist cohort, scholars, thinkers, curators, and activists who are interested in issues of positionality and privilege. I suppose that in the simplest and most complicated sense, my audience is one interested in issues of difference, otherness, and diasporic culture. I question ideological frameworks of meritocracy, social mobility, and distribution of wealth, because I want to, in small part, be in dialogue with someone, anyone, interested in discourse about the complicated social structure we live in.

Whirligig: Are you satisfied with the conversation the work is generating?

Angelica: I am. I find that when I am making work now, I have an audiene that supports me. I’m allowed to make work without thinking about who I’m going to disappoint because I already have an audience for it. I feel that a conversation is happening, and it is always satisfying and surprising to me. I’m always excited to see how and what people respond to.

With this last body of work, I wasn’t thinking about audience, per say, and it was read in drastically different ways. It had been a while since I had worked exclusively in photography, and it was interesting to have a conversation about process. People were asking me: How did you make that? This was satisfying because my work is usually read as more conceptual.

Whirligig: Do you think the work is or can affect change for disenfranchised individuals?

Angelica: Yes and no. It is a privileged position to be in, to be in this type of dialogue. I’m making art from an advantaged perspective, and I understand that the people who come in contact with it are coming from a privileged perspective themselves. I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that most viewers aren’t able to fully understand it from the disenfranchised viewpoint. I feel like, if anything, my artwork can create a dialogue. However, it’s tremendously difficult to create change through art alone.

When I look at the Chicano art movement, or the Feminist art movement, I see that it has been very difficult to affect change through art alone. Many of us continue to experience the same struggles despite past efforts to create change for those of us on the margins. Latinos are about to become the majority in this country, and yet we have little political efficacy. I do think that art can affect political efficacy because it creates a dialogue, but I’m not sure that art on it’s own can. Maybe it has for some people, but I don’t know that my art does that. I’m still trying to figure this out for myself—what change is created through the conversation. Because you know, we’ve talked. We’ve talked as groups, as individuals, as colleagues, as artist cohorts, as scholars, as thinkers, we’ve talked. And yet what is the real change that we are seeing?

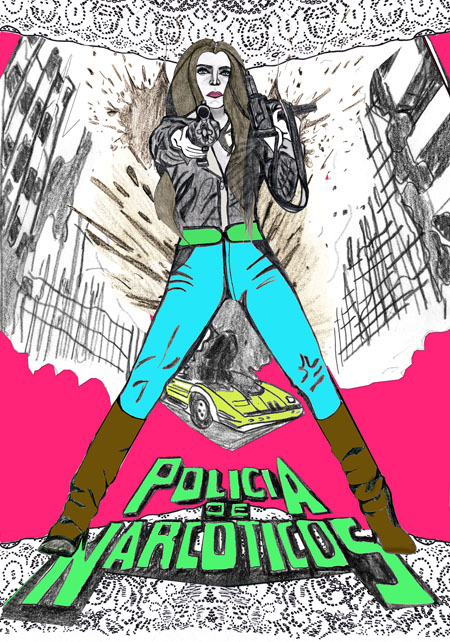

Whirligig: What compels you to create work about narco-culture?

Angelica: I grew up around mediated images of narco-culture—movies, music, television, and news. Culturally, narco-culture has been a part of my vocabulary since childhood—narco-traffico, narco-corrido, narco-cultura. I remember watching a movie as a young child, and although not the primary premise, drugs were being smuggled through a child’s corpse. As an impressionable child, I was fully introduced to the propaganda and culture of fear inherent within narco-culture. Even as a child, I understood that this was fear. A fear combined with the hype and allure that promised a way out of destitution. Narco-culture and social-economic class have a symbiotic relationship. What’s more, a recent, heavily circulated Rolling Stone Magazine video shows infamous drug cartel leader, El Chapo Guzman, conducting a selfie interview that emphasized a narrative of poverty and oppression. Dogmatic agenda aside, we’re dealing with very real social issues that cannot be dismissed as propaganda. Statistically, it is more difficult than ever to overcome the social economic class we were born into, yet (as Americans) we are taught the economic and moral principles of meritocracy—we are told that if we work hard enough, we’ll achieve something better for ourselves and our loved ones—this principle fails to consider the systematic failures of our society—primarily, that there is not enough equal opportunity.

I’m interested in narco-culture because, yes, it’s about subversive systems, power, control, greed, terrorism and corruption, but it’s also class warfare. I don’t condone intimidation through violence, crime, murder, trafficking, death, rape—but I have to acknowledge that these atrocities are featured in any number of narratives that are underscored by the search for a better life. The search for “something better” is often paved with hardship, unfairness, and desperation. It’s complex and rooted in issues of survival that almost always lead to corruption and criminal behavior. Narco-culture often affects communities that have no other recourse, plan, or opportunity. There’s a reason that the glamorization of narco-culture is something that preoccupies the media and peeks our interest through pop-culture references. Narco-culture is a contradiction—romanticized and appropriated by the very people is hurts the most. Guns, violence, destruction—these are the things that affect the least privileged in our society. This is what I’m interested in exploring, how one effectively grapples with issues of inequity with little to no political efficacy.

Whirligig: What do you make of the recent run on El Chapo style shirts and the Sean Penn interview with El Chapo?

Angelica: It’s interesting because I just read something that Sean Penn said, that the interview was unsuccessful because it didn’t affect policy on drug trafficking. And I thought: That was his point? That he would actually think that one interview would affect drug trafficking policy! It’s going to require so much more because it’s so complex. It’s thought-provoking in terms of the notion of change and what affects it. We are a society that has been taught that one person can affect change, which is bullshit. One person, one thing, one event cannot affect change. I’ve lived long enough to see horrific, monstrous events happen repeatedly, and I used to think that those events in themselves would create change. Now I see it more in terms of responding through a personal sense agency.

I recently attended a talk by MacArturos (Latino MacArthur fellows), and someone in the audience wanted to know who tomorrow’s leaders are. People want to know: Who am I following next? One of the panelists responded, “The thing that your generation needs to do is to stop looking for leaders and be the leaders.”

Getting back to the shirt-style question, there’s propaganda and consumerism that comes out of anything that’s extreme or easily ridiculed—it’s so obvious and so matter-of-fact. This whole thing is a spectacle.

The night I got the little ping on my phone that El Chapo and Sean Penn did this interview, I thought, of course, it’s only the next step in the spectacle. People don’t take it seriously; they think it’s funny. On the other end of the spectrum we have something like Donald Trump running for president. We aren’t being asked to take our political actions seriously. There is sarcasm and paradox in everything. Collectively things are so complicated, and we’re in real trouble. The fact that Sean Penn went into the jungle to do this is such a farce.

When Pablo Escobar was at the height of his trafficking, he was like the seventh wealthiest man on the planet. People had photos of him in their homes like he was a saint. People are going to latch onto anything that is fantasy-based, which is one of many things that interests me about my students. Millennials are really into things that are fantasy-based. We are escaping. We are living vicariously through a drug lord in hiding. We think, isn’t he a bad ass because he could escape from jail.

Whirligig: What is this fascination and romanticization we have with things that are below our moral compass? The run on El Chapo style shirts is by upper and middle class white guys.

Angelica: I call it evolved morality. When things that were completely off limits in recent memory become mainstream through socialization and conditioning. I think the obsession white middle or upper class kids or men have with El Chapo, who is a marginalized figure, is extremely gender-based. There’s going to be a fascination with these types of figures because what’s tougher or more badass than a Mexican drug lord. It’s the same with hip hop. Hip hop is incredibly homophobic, misogynistic, and can even be racist, and yet the majority of people that purchase hip hop music, that listen to hip hop music, are middle class white boys. In part, because it tells them something about toughness and hyper masculinity.

Whirligig: Is this something they are not able to embody?

Angelica: Yes. Hyper-masculinity is something that they are taught to value. It’s about “everything that I am not,” and “what is toughness?” It is very interesting and again, a contradiction.

Whirligig: Can you talk about the challenges of chairing a university art department and working with today’s developing artists. How are both of these affecting your thinking and your making?

Angelica: This is a challenging question. I find myself in an academic setting that is shifting drastically. The program I chair is socially driven, so we encourage students to address issues that are important to them, to think about their position and how it relates to others, and what it means to be creating community-sensitive work. That said, the disconnect between teacher and student is greater than I’ve ever seen.

How do we critically engage a group of individuals that have completely broken down the third wall—that is to say, there is no privacy in their lives; and “knowledge” available on demand. Exposure and lack of privacy is just par for the course, and they often view scholarly activities as optional—often placing little to no value on writing, traditional research, or even reading. Ironically, if they valued theses academic tenets, they would be the most informed, critically thinking, over sharing demographic we’ve ever seen. This makes our jobs as educators more difficult—the student expectation is one that circumvents long held social and academic tenets, and further upholds a student driven culture that treats academic requirements as light suggestions. This logic manifests in behavior such as skipping class because you can find a similar lecture on YouTube.

This brings me back to the disconnect between student and teacher—we are experiencing a real academic shift, and I don’t see it as a trend. Most educators don’t feel that they need to change the way they teach (after all, this seems to have worked for the last century). Teaching is challenging; chairing an art department in challenging. Educating artists who will become the new creative leaders requires more than just arts training. As an educator, I now have to consider my student’s psychological, philosophical, and academic well-being—that is to say, aside from the educational component, we are now being asked to consider a student’s emotional well-being and their life outside of what we know. To answer your original question, teaching and chairing affects everything.

I tell my students, “You can only do your personal best,” because they get so overwhelmed—we’re talking about positionality and what is their place in this world, and they get so overwhelmed by vast amounts of information. I get overwhelmed by the information. I have to take this advice for myself as well—”where is it in this whole academic system that I can affect the most change? At the heart of it, and this seems like a simple, obvious answer, I affect most change as an educator. I love what I do, but sometime it doesn’t feel like it’s enough.

I also feel that this is a question that artists have more than other academics: Why am I teaching? Why am I doing this? Why am I in academia? I know artist colleagues who have either left or rejected full time tenure-track teaching positions because it doesn’t fit in with the ideas they have for themselves. It’s about finding a balance between being self-sufficient and productive.

Whirligig: I think in part it’s because to teach and to be a creative person we access two different parts of the brain. For many other academics teaching is about their research. I think it’s harder for us to make the switch in our brains between teaching and our research, because in the creative disciplines we go to a difference place.

Angelica: We do. I think there needs to be more reciprocity for us in our teaching. It is so hard for administrators to understand what we do and what our research is. I don’t know if others who teach in the humanities are able to come home from work and turn it all off. Because I don’t, not ever. It is a constant, 24 hour, seven days a week situation when you are an artist, and if you are serious about it, and in it for the long haul, it’s a lifestyle not a job.

Whirligig: And teaching is that too. They never end with each other.

Angelica: Yes, absolutely. I was invited to speak at a conference at the Ford Foundation on Art and Social Engagement in January, and I was talking about myself as an artist educator, and this constant dialogue and negotiation we have with our students, and about the issues specific to Millennials. It’s a challenging notion, art and social engagement. The social woes are blatantly obvious, but not all artists are interested in community. That, coupled with the shift we are seeing in academia, is problematic. I feel like other academics aren’t necessarily willing to talk about this change because they see all of this more as a trend. They have been doing this for 30 years and they think this will also run its course. But for me, as a relatively new educator, I am much more interested in the social and cultural implications, which can’t be ignored. I am seeing that this is an impossible situation for us as artist educators, to be here with these students that we feel we are not getting through to because of this massive separation of ideology and scholarship. There’s this disconnect between us and the students, and I’m so much closer in age to them. What is the disconnect between those teachers who are 30 to 40 years older than them? I don’t think they are having the same dialogue with them. Are they talking about their students’ needs, or do they say, “This way of teaching has worked forever and this has to work now. They, the students, have to come around to us.”

We know for a fact that the Millennial generation is a generation that does things on their own terms. We know that. They don’t have to come around to our way of thinking. They are strong. They are powerful in numbers. They don’t have to.

Whirligig: How are they going to survive?

Angelica: They’ll do it. They’ll do it because we will come around to them. The irony is that they have the ability to be great thinkers in that they have massive amounts of social, cultural, and intellectual information presented to them on a daily basis. They are innate cultural critics, but just as great as their ability to access this information is their complete disregard for it.

Whirligig: Because their tools are so much more sophisticated?

Angelica: Yes. They have no real understanding of the ease and access that is available to them. Why would they?

Whirligig: You teach a course on media theory at CSU Monterey. What are the current trends and issues that you discuss and how do you see this course of study affecting your students?

Angelica: I find that my students are grappling with a variety of issues specific to their age group that are no different than issues we dealt with. However, they are coping in a very different and new way. I’m seeing higher rates of depression, and they’re less engaged when discussing issues of equity in terms of media representation. However, they’re more engaged with dialogue related to social media and the unintentional social and personal consequences related to these types of tools. More recently, values and empathy seem to be a common theme, and there is more dialogue about the intellectual and emotional tools available to navigating the complicated social issues of gender, race, sexual orientation, social economic class, etc.

Most of my students have never engaged in media studies, and I’m still surprised when they say something like “we talk about real issues in this class.” As opposed to what?” I ask. There is certainly a disconnect with what they’re learning and how they apply it. They’ve never been asked to examine the effects of media, or speak to the profound effect it has on their lives. Few have ever been asked to examine or critically formulate opinions on how media representation relate to our understanding of the the world.

In my Media Culture course, we specifically examine a visually saturated society made-up of high and low culture from a millennial perspective. My students, for the most part, are young adults, and they are being told that they are lacking intellectually because they are digital natives that don’t know how to navigate a post-Internet society. How’s that for a social disconnect? It’s interesting. . . they have a value system that no one ever asks them about. They have empathy, which people seem to forget. As I mentioned before, in truth, they are a visually saturated community, which makes them innate cultural critics. They conduct anthropological investigations every day, yet aren’t being asked the right questions or given the right tools to engage critically. Instead, they are told that they are glib and have no scholarly efficacy. In many ways, it’s unrealistic to expect our students to have the wherewithal to critically formulate positions on privacy, or navigate the thousands of images and complicated social issues that fill their Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter feeds. By anyone’s definition, this type of visual stimuli is characterized as confusion, clutter, and chaos—calling it information is reductive because it negates the fact that we/they have not been given the tools to navigate this complicated social structure we live in. This generation is powerful (40 million strong), yet they aren’t given the tools to navigate the world they live in. I make them aware of that, it pisses them off, they begin to question, analyze, think critically, and hopefully that contributes to their political efficacy.

Whirligig: What specifically are you seeing as their value system and how is their empathy manifest?

Angelica: They are less inclined to tell you what they care about because nothing is ever phrased for them in that way, which is confounding. They have values, they care about their family and friends, and have principles, beliefs, and standards no different than you and I; however, they relay all of this differently. Their social interactions and cues are different. They have a different relationship with social commitment, public and private, and have had to develop their own etiquette and rules as they relate to a post Internet society. They are trying to navigate a hundred different things, so perhaps it comes off as glib. If I had grown-up with the same tools, tools that present a hundred different possibilities coupled with an inherent inability to multi-task, it would take me longer to express my point of view as well. By the way, this inability to multi-task is not specific to them, none of us can do it well.

Whirligig: Do you think they are concerned about judgment?

Angelica: Perhaps. I’m trying to get to the bottom of why it’s difficulty for them to express themselves, or why it seems to be different than the way students expressed themselves even five years ago. My colleagues are telling me the same thing, that across the board their students are not having opinions about abstract ideas. They do have opinions and about real issues. For example, last semester I had Active Shooter Training. When I went to class that day, I told them that I had just come from this training and wanted to have a conversation about it. They had so much to say on school shootings. When we look at media, there is a lot of theorizing on school shootings, but none of this information actually comes from the students. So, perhaps, we’re just asking the wrong questions. I am working to discover what issues are important to them, and this is difficult because they are not always willing to vocalize them. They are writing very interesting responses to the things they read, but when I ask them about their responses in person, they have a harder time. Fear of public speaking isn’t new, but this is different. Perhaps if I asked them to instant message me in class, I’d get more responses.

Whirligig: I have also noticed an increase in student passivity and expressions of fear, and this is across the board. Although it still exists, basic survival is no longer an issue for most Americans. Do you think this lack of forced struggle and focus on survival is creating a generation of Zombies?

Angelica: The short answer is yes. There is a dehumanization aspect to all of this, and over time it contributes to a culture of fear. We respond very well to fear in the sense that we allow it to dominate our lives. Again, they are dealing with visual chaos and the complicated virtual systems that come with very real unintentional consequences. They’re distressed and being asked to take risks, and that’s paralyzing. They are less inclined to take risks. That in itself isn’t new, but I do find myself coming to terms with the first ever child-centric society, where everybody gets a trophy, and their expectations are so high for doing so little. This behavior can absolutely be seen as mechanical or automated.

Whirligig: What tools do you think they need and when and how should they be introduced?

Angelica: Do you mean as artists?

Whirligig: So that they can be self-empowered.

Angelica: Recently, I was in a conversation about the way that we train artists. A lot of students are taught that failure is not an option. In the arts, we seem to always have an apologetic attitude about our failures. For some reason, our students always get compared to students of other majors. For example, in business, if you go out there and give a presentation and fail, they tell you, “You are going back out there and you are going to do it again, because you’re the best.” So there is this pumping up of the self that we do not readily engage in, in terms of giving artists the tools to succeed. We know that failing and being an artist go hand-in-hand.

Whirligig: We have to fail.

Angelica: Yes, because that’s a primary component of how we get to the next place, it is a primary element for our creativity and how we analyze and think critically. These are hugely important experiences for us. I also see the tools needed as being those that have theoretical foundations because this is how they are going to learn to articulate themselves and move forward. Even if they don’t appreciate them at the time, they will appreciate it later. I think it is important to give them those tools even if they reject them. Theory, learning to write, public speaking, taking courses in various professional practices. . . these tools are so incredibly important.

Whirligig: What are the pros and cons of our mediated culture? Is it all about entertainment?

Angelica: It’s a lot about entertainment. Anyone who is writing about pop culture talks about the entertainment value, and how it is not up to television or movies to have any educational value or component. Yet, the disconnect is that we understand mainstream media as having this incredible ability to affect perception. So yes, it is about entertainment.

We are taught to digest entertainment in this really strange way because we don’t believe that media has the ability to affect perception. We don’t like terms like brainwash, but that’s what it does. It is so visually saturating. There is so much visual pollution, so much persuasion, and very little reciprocity. We need to consider that media affects you and I, but especially young people who are still critically forming positions. Media affects the way they behave with their friends, the way they behave in relationships, the way they dress, everything comes from what they see in the media, yet no one actually phrases this in terms of social consequences. What I try to do is instill, through media studies, the understanding that we cannot be passive consumers, that we have to ask questions.

Many of my students don’t realize they can say no. They can protest. I ask them, “Why are you giving up your privacy so easily?” They will say, “I have no other choice.” It is literally a social contract. They’ve given up their freedom, their voice without any sort of negotiation.

Whirligig: Do you mean their dependence on social media has taken with it their privacy?

Angelica: For sure. Their dependence on social media is just par for the course. They’ve taken choice out of the equation for fear of missing out, FOMO. For them, being disconnected means something entirely different than it would to you and I. The perceived consequence is different.

Whirligig: You went to Mills for grad school.

Angelica: Yes. I had a really positive experience there. Grad school stays with you in a different way than pervious schooling can. I feel as though the graduate school experience is a lot about what you have to give. I think a lot of people approach it as “what are you going to give me?” It doesn’t really work that way. I was surrounded by these really amazing people like Moira Roth, Hung Lui, Catherine Wagner, Anna Murch, Ron Nagle. It was a beautifully challenging time.

Whirligig: Both Glamorgeddon and Caprichos Anatomicos were quite diverse with many under-shown artists. At the same time, there was a similar aesthetic running through these exhibitions. What is your curatorial process?

Angelica: I’m concerned with creating community and opportunities for artists, and this almost always results in a curatorial project. In terms of process, these projects usually come together organically—I consider artists whose work I find both visually and intellectually interesting, and then I look at how things fit together: conceptually, technically, and visually. Sometimes it’s perplexing, but I enjoy disparateness and making connections where there seemingly aren’t any. Everything is connected, but not everything is interesting—I mostly start with interest: concern, relevance, curiosity.

Whirligig: Does the audience become the artists in the exhibitions, and are you seeing these artists or the larger audience making your specific connections?

Angelica: Yes. I hadn’t thought of it specifically in that way: Am I curating the exhibition for the artists? I suppose that I am because I seek exchange. Part of the reason that I curate is because I want to be in dialogue with the artists. Otherwise it would be miserable for me. I am constantly looking for ways to bring a sense of awareness into my life and curating, somehow, always results in something unexpected.

Whirligig: The pink limo ride with lecture and champagne during the reception of Glamorgeddon was entertaining and provocative; and an interesting discussion developed in which it was obvious that your audience was invested in your content. How did you conceptualize this event?

Angelica: Glamorgeddon was part of a curatorial residency at SOMArts Cultural Center, and was a larger collaboration between Johanna Poethig, Dionicio Mendoza and myself. During the planning phase, we were tossing around ideas for outreach events and connected programming. I suggested a limo lecture. A few weeks before this meeting, while walking in my neighborhood, I saw the most pretentious, flashy, hot pink, stretched Hummer Limo parked in front of a church. I photographed it with my phone and thought I’d include it in one of my drawings, but using the actual limo worked well with Glamorgeddon.

There were a few limo lectures as part of the Glamorgeddon closing reception that varied according to themes of capitalism. Amalia Mesa-Bains and I presented, It’s All About the Base: Racialized Bodies and the Popular Gaze; having a dialogue about race, gender codes, and the pornification of women in a gigantic, hot-pink hummer limo that embodied excess and hyper-masculinity seemed necessary.

Whirligig: I especially appreciated the visual aids that you held on your lap to illustrate the lecture, even though you didn’t get through all of them.

Angelica: No I didn’t. It’s funny because I have those visual aids, which consist of famously exploited backsides from J-lo to the Hottentot Venus. They are in my living room, and when people come over they’ll shuffle through them and ask, “What are these?” So, eventually, they all got seen.

Whirligig: For several years you and Binh Danh ran a gallery, Space 47, in San José. What were your objectives with this project? The highs and lows?

Angelica: Our objective for Space 47 was to fill a void. There was no place for us to exhibit, and although we never showed our own work, we were thinking of those like us. As emerging artists, we didn’t feel that we had a voice—we weren’t seeing the art of our peers, or hearing the dialogue that reflected the concerns of young artists in San José. There was no non-niche, local, or regional exhibition space that was non-commercial and offered solo exhibitions to emerging artists. We wanted to offer solo exhibitions, which are incredibly important to an artist in terms of landing other exhibits, grants, awards, residencies and developing an overall audience. We also wanted to provide a project space where artists could exhibit work without the added pressure of commercial viability.

In terms of highs, we were embraced by our community, and gave over 20 artists solo exhibitions, and awarded three artist residencies. There weren’t really any lows—it was hard work, but we were really young and willing to take it all on. The gallery wasn’t sustainable because we weren’t a commercial gallery, we were two artists working on a project. We made no money, and we paid for it out of our own pockets. I miss it, I miss that time—to me, it was successful.

Whirligig: I agree Space 47 was a lovely entity. We were sad to see it go as well. Do you think about running a gallery or project space again?

Angelica: I do. A project space/gallery is something I see in my future. When there’s time to be little more selfish in terms of the projects I take on, I’d like to recreate a space like that. A lot of my creative ideas are deposited for later use. The projects I take on now are less organic and many are residual. I feel that a gallery or a project space will come down the line. However, for now, I want to do smaller projects that are in the vein of Space 47, and I see that happening soon.

Whirligig: Collaboration appears to be a strong aspect of your practice. Can you talk about this?

Angelica: I spoke to some of these aspects earlier. I find that artists of my generation, Gen X and early Millennial, were raised on tenets that prompted the creation of our own opportunities as essential to our survival as artists—not that artists weren’t doing this before us, but this was at a time when community engagement and social practice exhibits were entering museums. So in a way, it became more acceptable to take your career into your own hands (DIY). More and more of us began curating exhibitions, proposing artist panels and dialogues, opening galleries and project spaces, developing collectives. Everything we did was considered part of our artistic process (from teaching to curating to working in the studio). For me, collaboration is at the core of artistic practice, and I think it’s smart to think of teamwork and partnerships as the key to sustainability.

Whirligig: What do you think this means for the larger art world considering our earlier conversation regarding today’s art student?

Angelica: I try to impart trust and collaboration as much as I can, but 18 year-old artists have very romantic notions about what it means to be an artist.

Last year I put together a visiting artist series that was exclusively about artists who were collaborating. My students responded optimistically. It opened up possibilities because they began to understand that they don’t have to do things on their own. It’s a major breakthrough when an artist understands that they do not have to create things alone.

When I was their age, there was still, very much, this idea of the lone artist working in the studio—everything is about you, the genius, lone artist. I was never taught about reciprocity, about community, about collaboration and dialogue, and how that would essentially affect my work and make it better. I’ve heard that surrounding oneself with intelligent people is the key to success because success is about networking, about collaborating, about sharing, and about community. Building a community of artists is huge in terms of long term benefits, and is essential for any artist.

American society values competition. We are taught from a very young age that we need to be competitive in order to be the best, or the better one. We are competing for multiple things: grants, space, exhibitions, audience, donors. The beautiful thing about collaboration is that it also disempowers competitiveness. When I collaborate, I’m not concerned with whether someone is giving more or less because I know whatever percentage I’m giving is my best. Maybe I’ve been blessed with good collaborations. In the end, our artist community is the only thing that we have. Artists are always trying to get away from that, especially in art school, which is very ego-driven. Yes, solo artists can go out into the world and find some success, but if they don’t have a community to come home to, they have nothing.

Whirligig: Your upcoming project with Juan Luna-Avin, Club Lido at Empire Seven Studios, opens in February. What should we expect from this event?

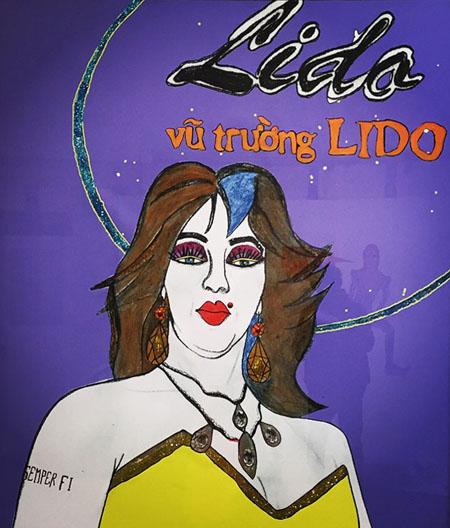

Angelica: Juan Luna-Avin and I have been working collaboratively since 2006. We’ve done various inter-disciplinary projects that revolve around the cult of personality in pop culture through fictitious characters, sub-cultures, urban myths, and legends. A few years ago, I was invited to participate in a group exhibition curated by Kevin Chen at Intersection for the Arts in San Francisco. This exhibit examined the impact of Asian and Latino cultures. I had been wanting to create a body of work inspired by an entertainment venue in downtown San José called Lido Night Club, and I felt it was a good collaboration for Juan and I. Although San José is home to a large Mexican and Vietnamese demographic, these two cultural groups rarely come together. We wanted to celebrate the mash-up, duality, and hybridity that is Club Lido.

The cultural balance at this venue teeters between a downstairs Mexican cantina and an upstairs Vietnamese dance club. Juan and I proposed a narrative where these two cultures intersect in both a fictional space as well as a real location. This project began with Intersection for the Arts, continued on to San José Institute of Contemporary Art, and really evolved at Riverside Art Museum. We felt it was time to bring it home with an exhibit titled Club Lido: Wild Eyes & Occasional Dreams at Empire Seven Studios in San José. For this exhibit, we will continue looking at the cultural similarities of immigrant and marginalized groups through the lens of this unique dance club and bar via sculpture, drawing, and sound.

Whirligig: You and Juan are collaborating on both the concept and the visual artworks for Club Lido. How does the process of making imagery play out between you?

Angelica: Our process started out as independent activities or assignments, but as our vision for the project progressed, our individual aesthetic contributions began to coalesce and became less autonomous, which we think is a positive outcome for the collaboration.

We did quite a bit of research for the source material together, so there was a lot of pre-dialogue about the characters we would draw. There are certain production components that we know will be independent, which are delegated by the same influences and individual strengths that led us to collaborate in the first place. For example, I always handle the digital components, while Juan works on the more analogue zerox and collage components. Another example is that we initially work on drawings separately, but I often pigment mine digitally, while Juan always adds pigment by hand. Our aesthetic vison works well together, and as the project progresses, the delineation of where his or my drawings begin or end becomes increasingly subtle. For Wild Eyes & Occasional Dreams, we literal sat in my studio, and worked on the mixed media drawings side by side, making individual and joint aesthetic decisions that included everything from which variation of color to use to various bling choices.

Whirligig: How do you take a break from the invasiveness of mediated culture? What do you do for fun?

Angelica: I find more and more that what I do for fun is truly basic. I spend time with people that I care about, and try not to put myself in circumstances where I am not enjoying myself, or go to places I don’t want to be. My studio, my home is a place where there is peace and justice and no judgment. I am so fortunate, really, to have people in my life that listen and give good constructive criticism because I have so much growing to do. I know this sounds cliché, but the most joy/fun I have is when I am working on my art. That is when I feel the happiest.

Whirligig Interview by Nanette Wylde.

Angelica’s website: angelicamuro.net

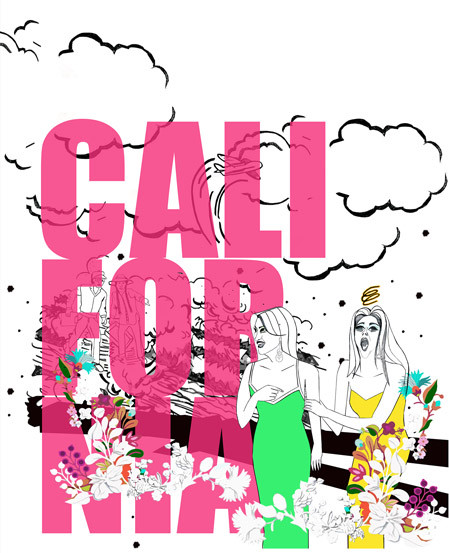

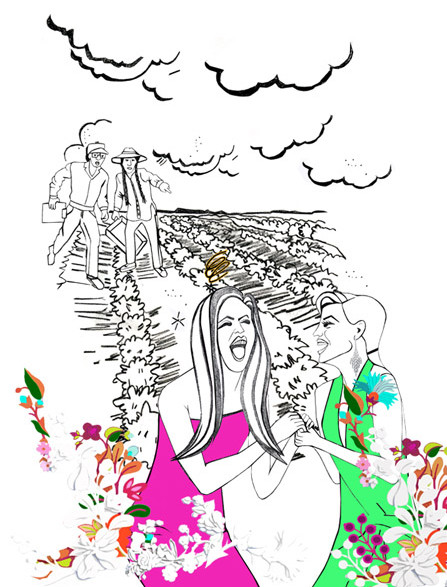

Images courtesy and copyright of Angelica Muro. From top: Agricultural Workers series (Cali-for-nia), pigment print, 2012; Policia de Narcoticos (from the Packing Heat Series), pigment print, 2012; Narco-Language (Narco-Queen), pigment print, 2015; Untitled (from the Packing Heat Series), pigment print, 2012; Agricultural Workers series (Queens), pigment print, 2008; Agricultural Workers series (from triptych), pigment print, 2007 Muro & Juan Luna-Avin, Roman y Lilia, mixed media on pigment print, 2016; Muro & Juan Luna-Avin, Jane, mixed media on pigment print, 2016; Muro & Juan Luna-Avin, La Doña (Maite), mixed media on pigment print, 2016; Muro & Juan Luna-Avin, Club Lido, mixed media on pigment print, 2016.